Industry Update Q1 2025

- Special Topic – Airline Industry Default History Through 2024

- Macro-Economic Background

- Traffic and Aircraft Demand

- New Aircraft Supply

- Airline Industry Financial Performance

Where are all the early retirements? Is it different this time?

Airline Industry Default History Through 2024

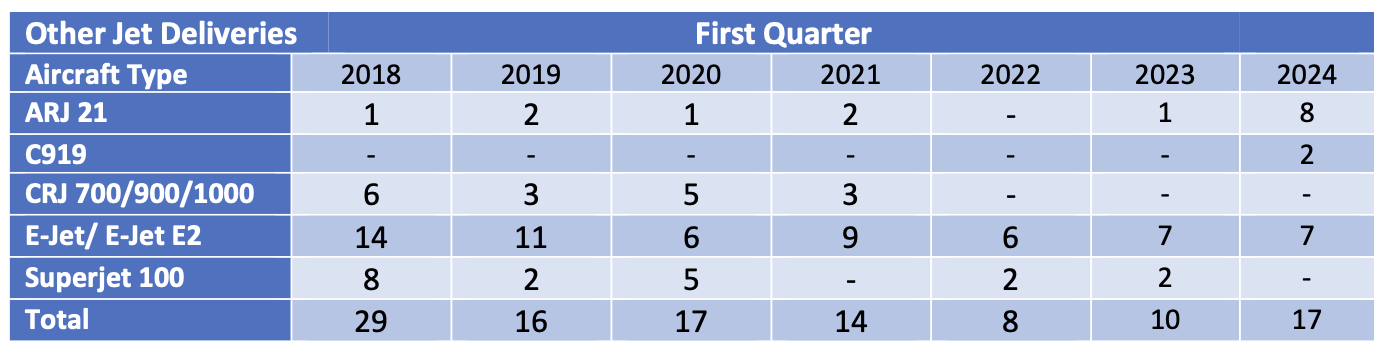

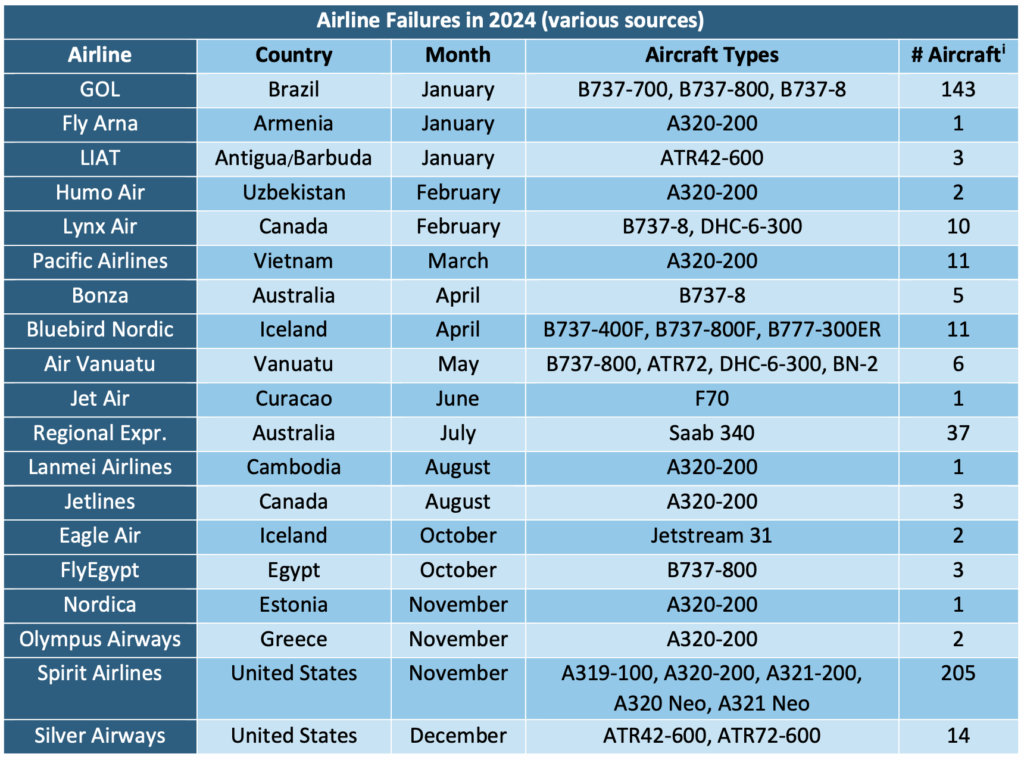

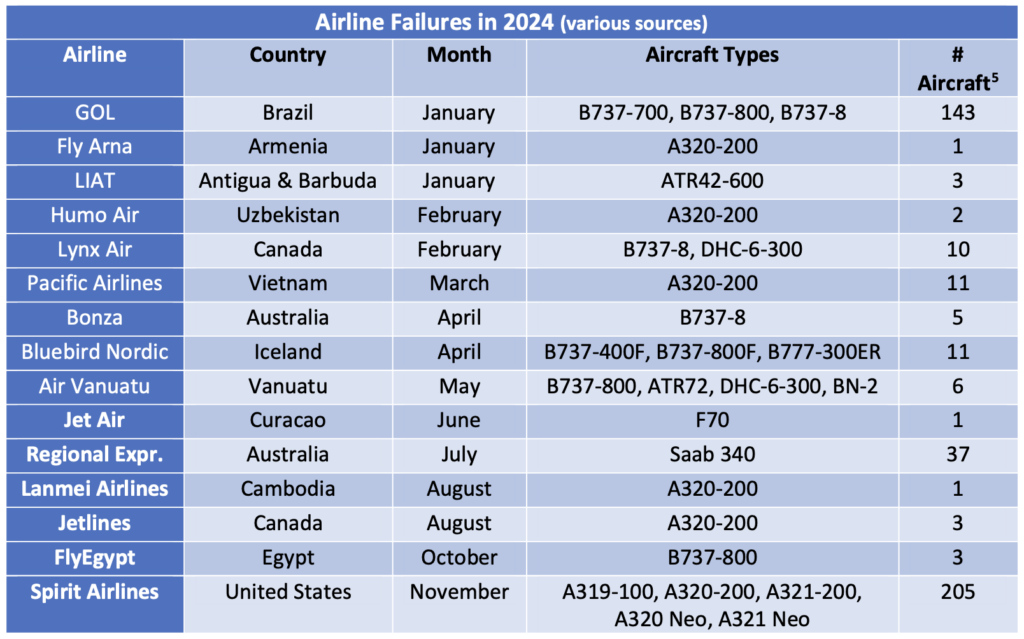

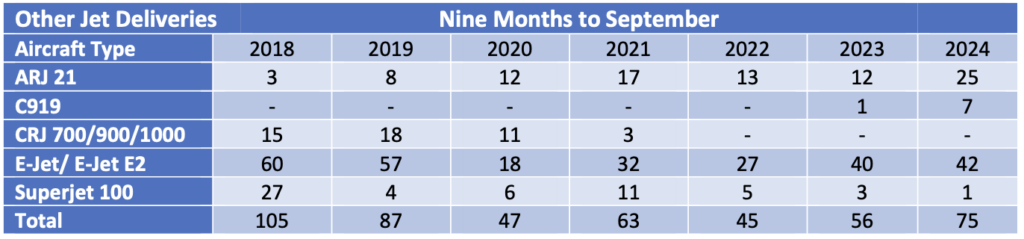

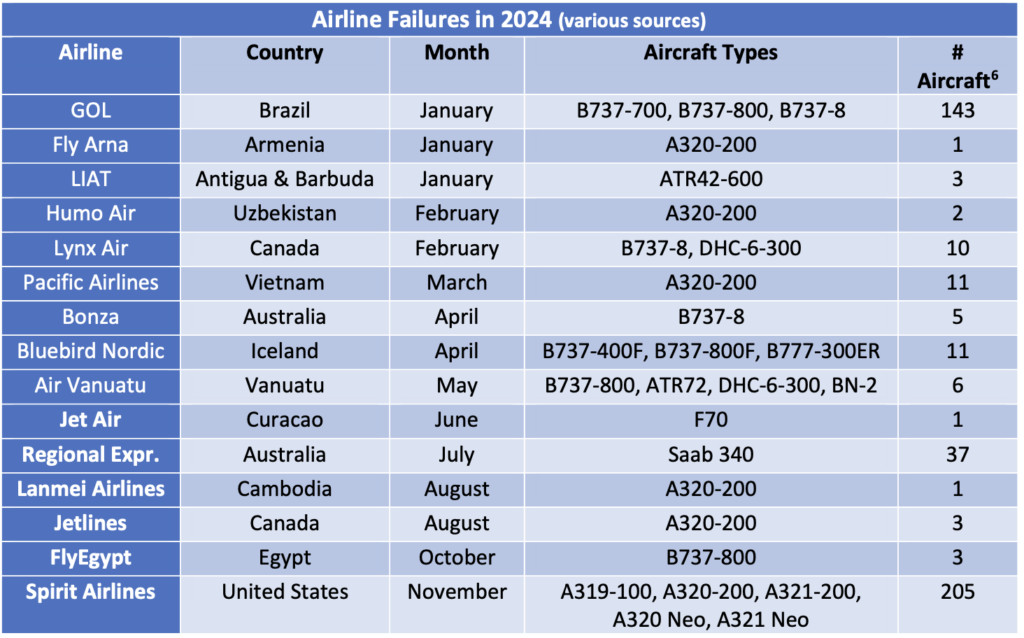

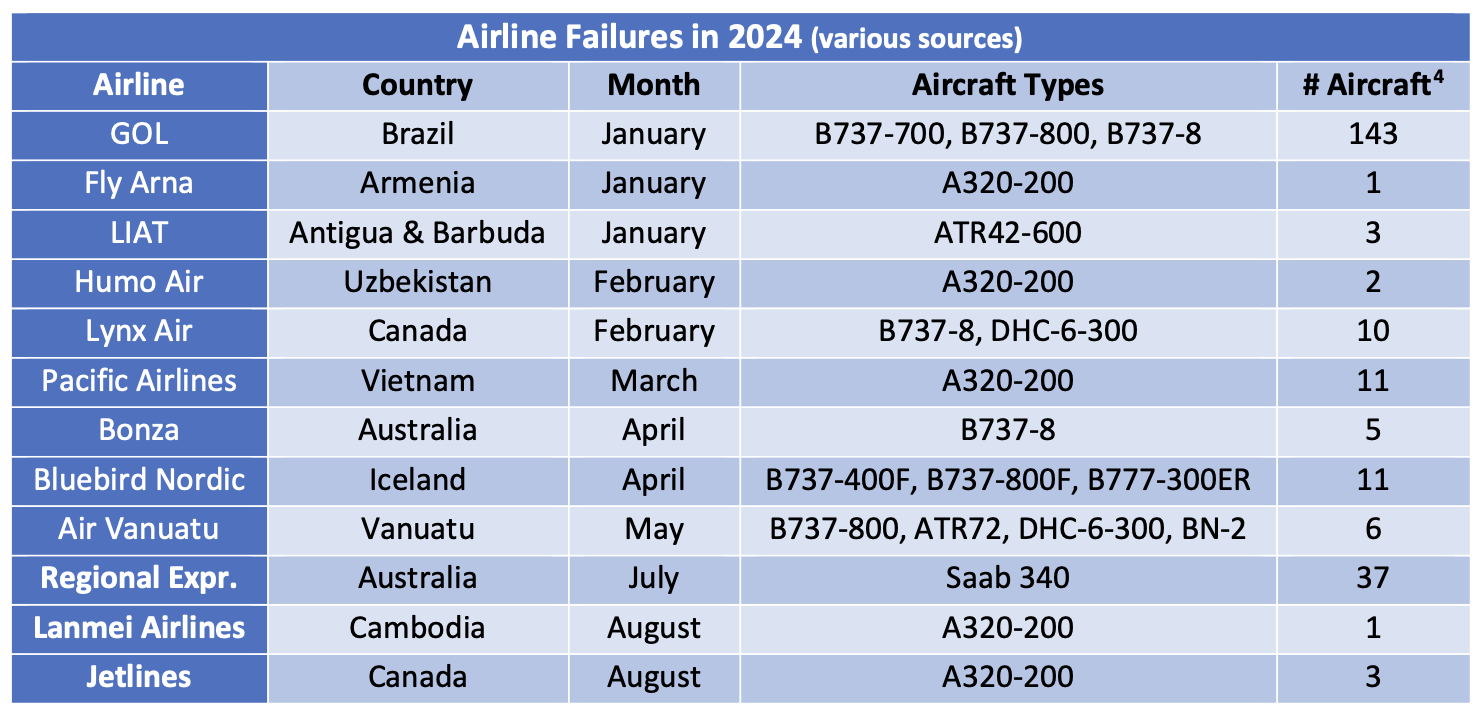

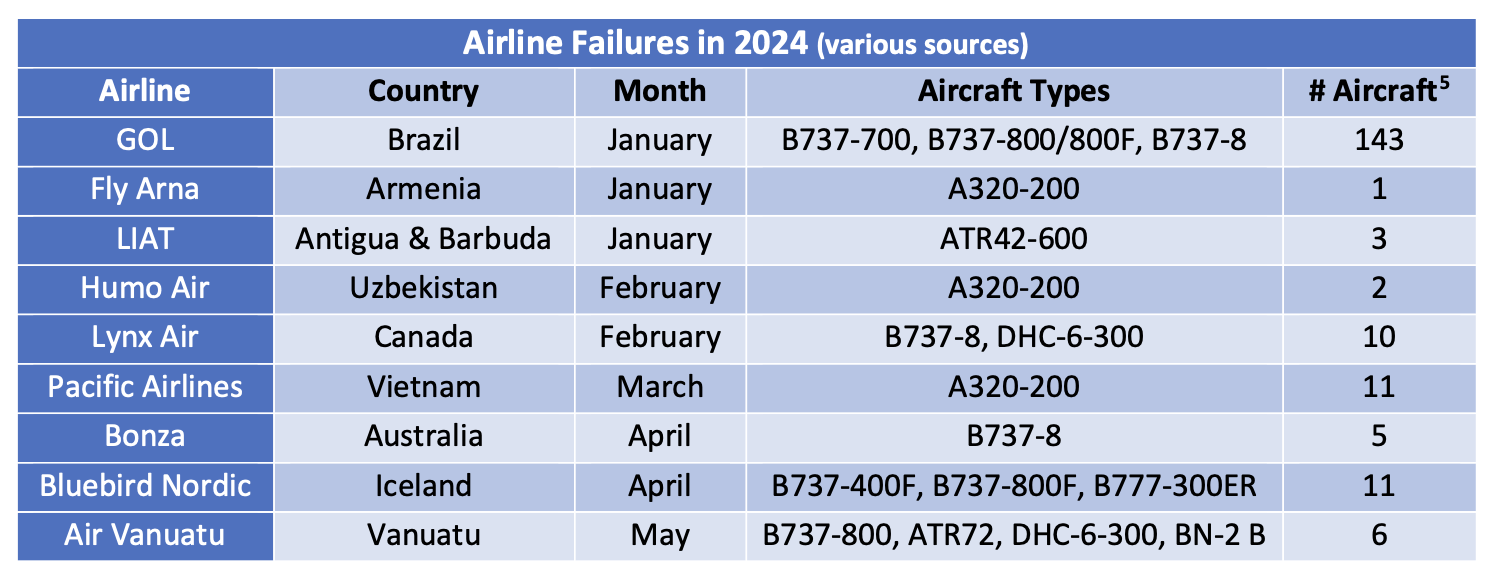

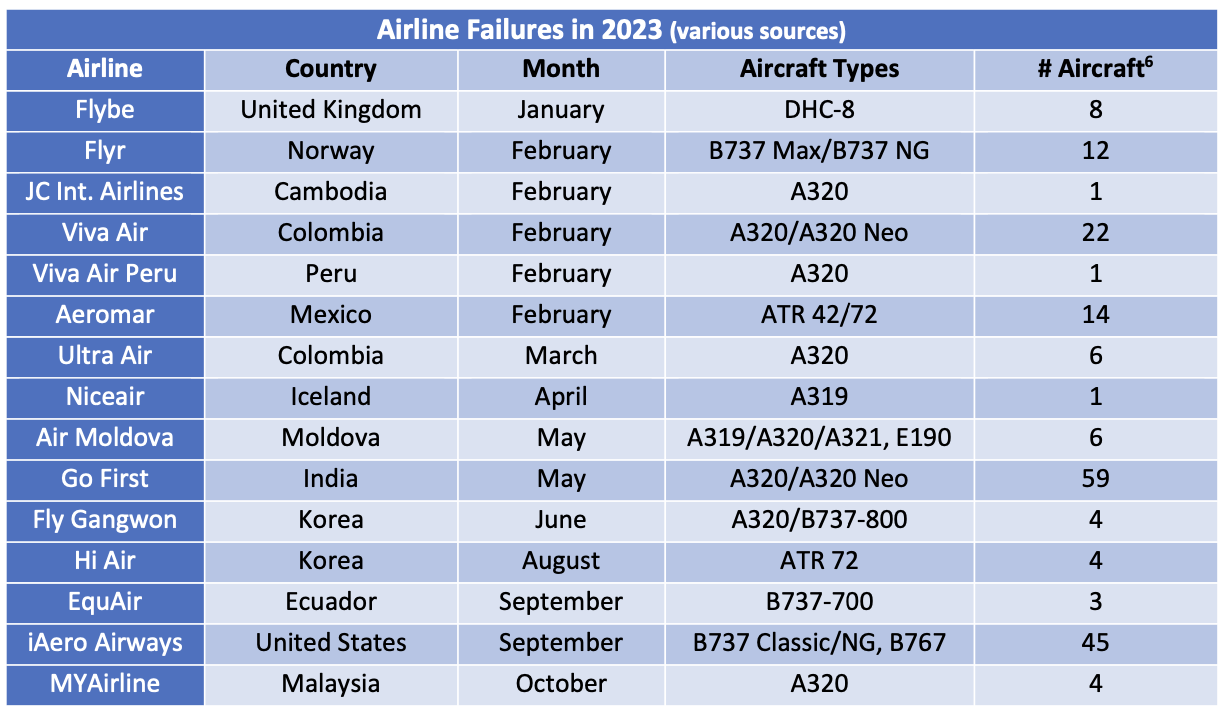

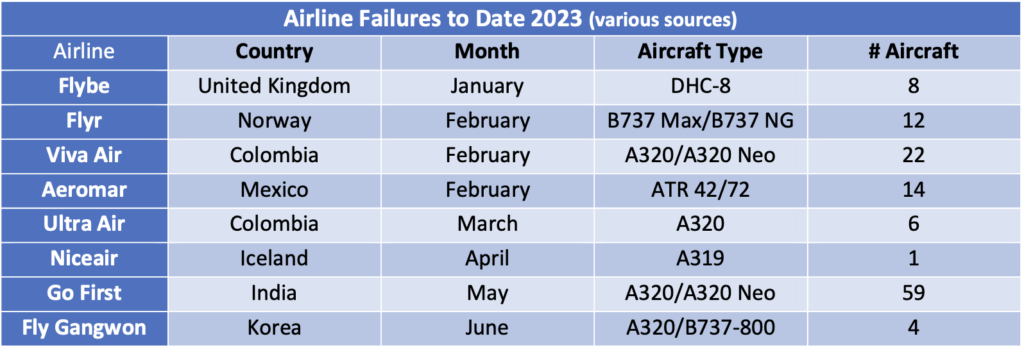

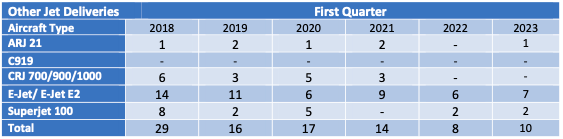

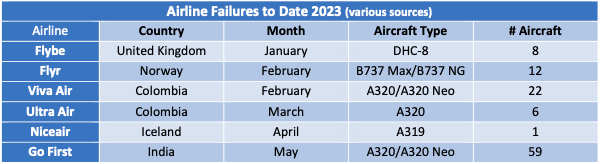

Before putting 2024’s default experience in its historical context the table below shows the final list of airline failures we have been able to identify for the year. We have excluded CSA, OTT Airlines and Vistara as these airlines ceased operations due to merger and Air Malta – the latter ceased operations but was immediately succeeded by KM Malta Airlines, also owned by the government of Malta and operating at least some of the aircraft previously operated by Air Malta. We classify this as an orderly wind-down rather than a default.

The map below shows these defaults were dispersed geographically but defaults by numbers of affected aircraft were highly concentrated in the Americas, accounting for 379 out of 461aircraft (82%). The big driver of defaults in North America was the difficult business environment for low-cost airlines and in Latin America it was the hangover from the airline defaults that occurred in the pandemic. The airlines that restructured through bankruptcy at this time obtained a sufficient competitive advantage that those which did not ultimately have had to follow.

Sirius produces proprietary estimates of global airline defaults because we think there are important issues around credit risk that arise at the industry level as well as at the level of the individual airline, and we cannot find any alternative source with the coverage we would like. The appendix to this report gives a detailed description of our methodology – probably the most important point to bear in mind is that we exclude small airlines for the sake of practicality so that only 8 of the 19 airlines listed in the table above are included.

The rating agencies produce historical statistics by industry, but their universe of rated airlines is quite small (typically 25-30 airlines at any given time) as they only cover airlines that make use of debt capital markets funding.

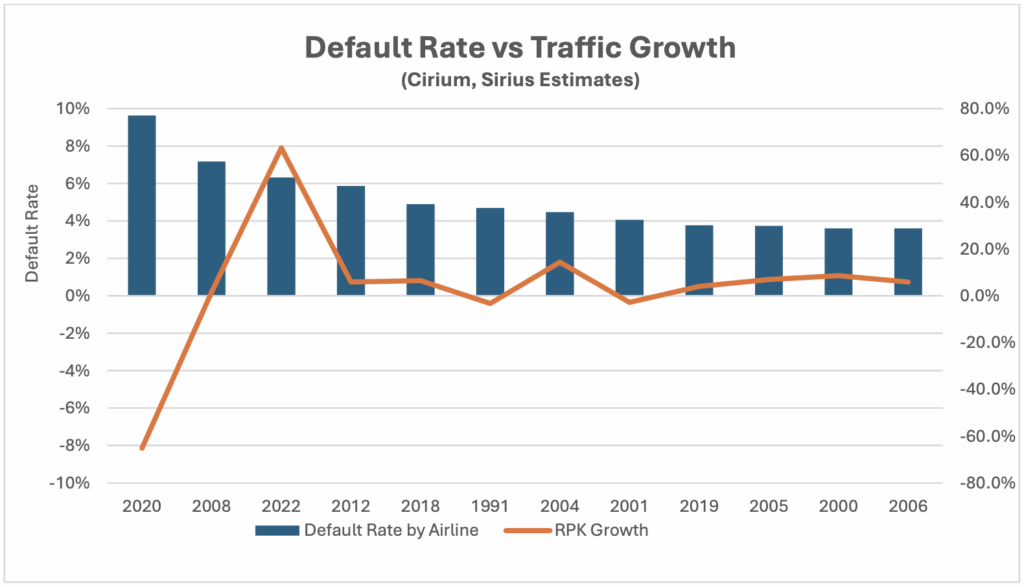

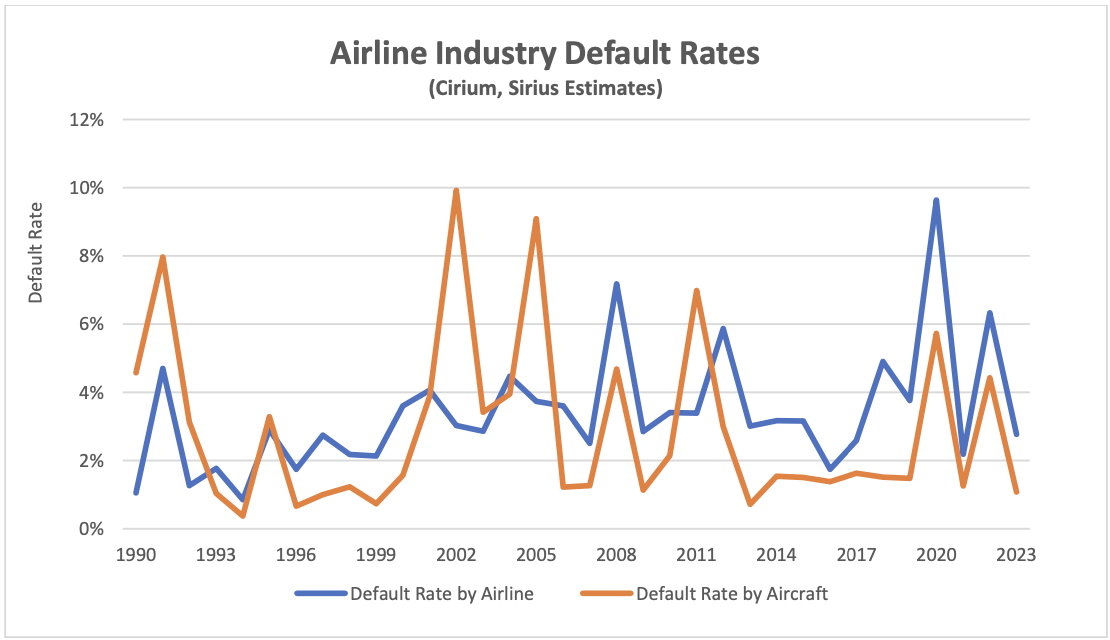

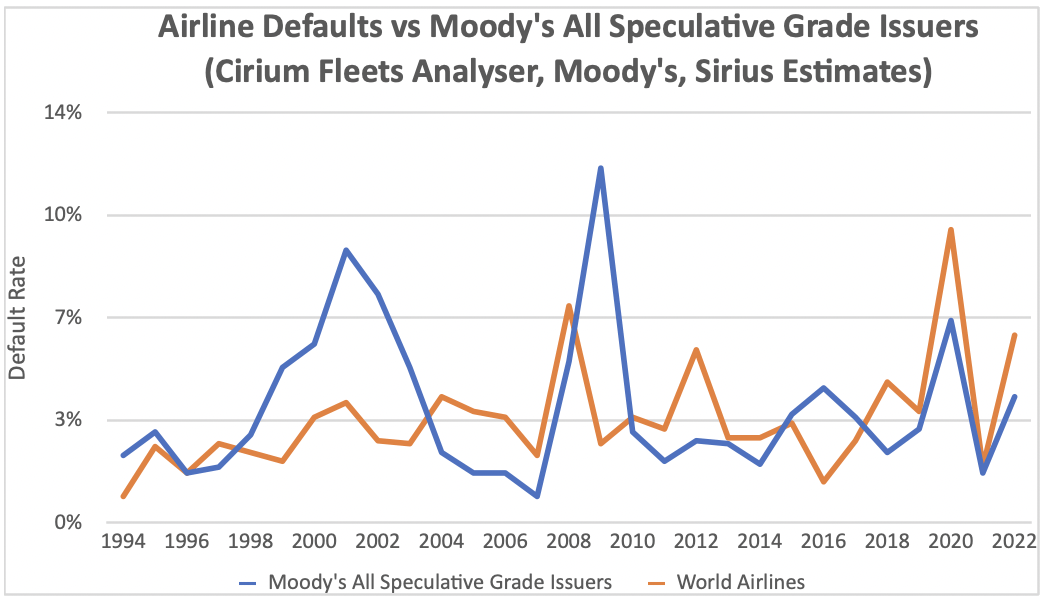

Like 2023, 2024 saw a more normal level of defaults following the shocks of the pandemic in 2020[1] and Russia’s expropriation of lessor-owned aircraft in 2022. 2024’s default rate by airline was 3.7% compared to an average of 3.4% p.a. from 1990 and the default rate by aircraft was 2.0% compared to an average 2.9%. This means that the average defaulter had a smaller than normal fleet which is good news for financiers who had to remarket aircraft. The historic correlation between these two default rates is quite low at 0.36, reflecting the divergence caused spikes in defaults by aircraft when very large airlines such as the US majors enter bankruptcy. The analysis presented below focuses on defaults by airline to make for a more digestible read and the pattern of outcomes is broadly like that for defaults by aircraft.

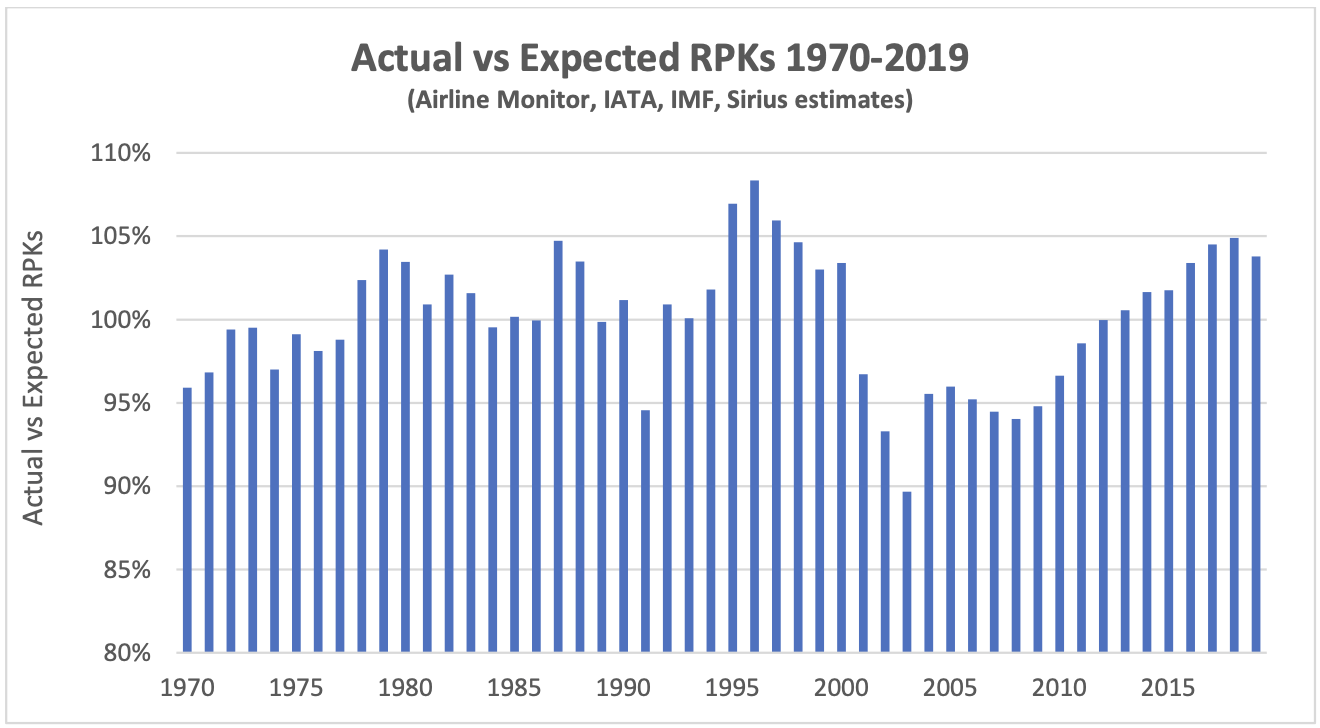

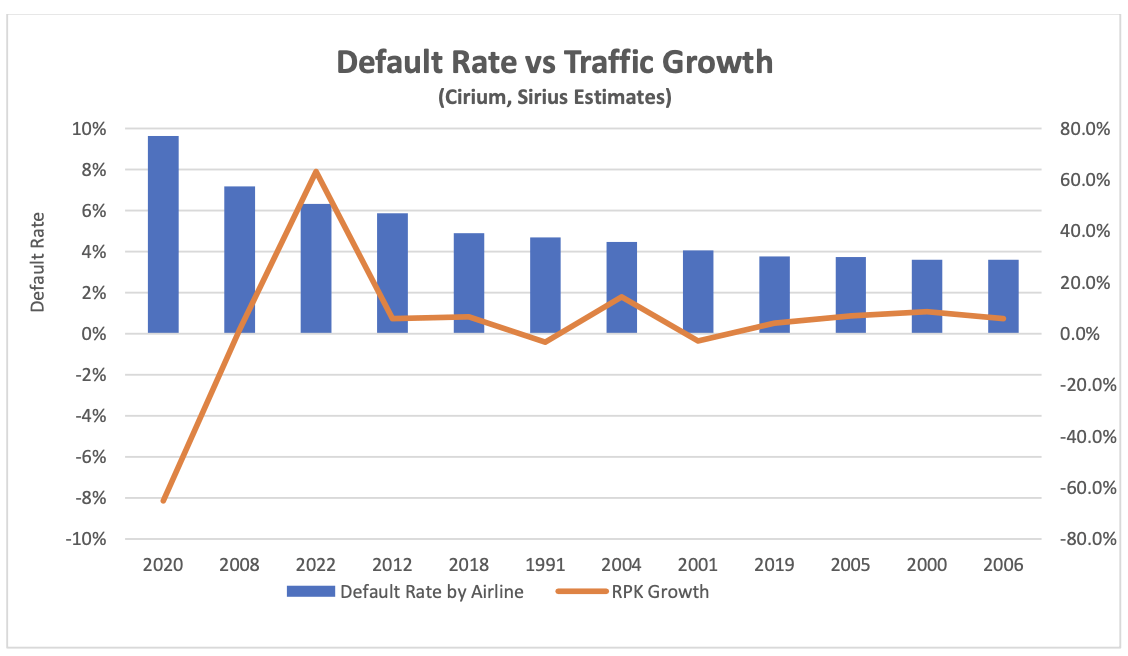

One notable feature of our estimated default rate is that it is not highly correlated with traffic growth. The chart below compares the default rate by airlines with traffic growth for every year where defaults were above average with the highest default rates on the left. Traffic declined in only 3 of the twelve years concerned.

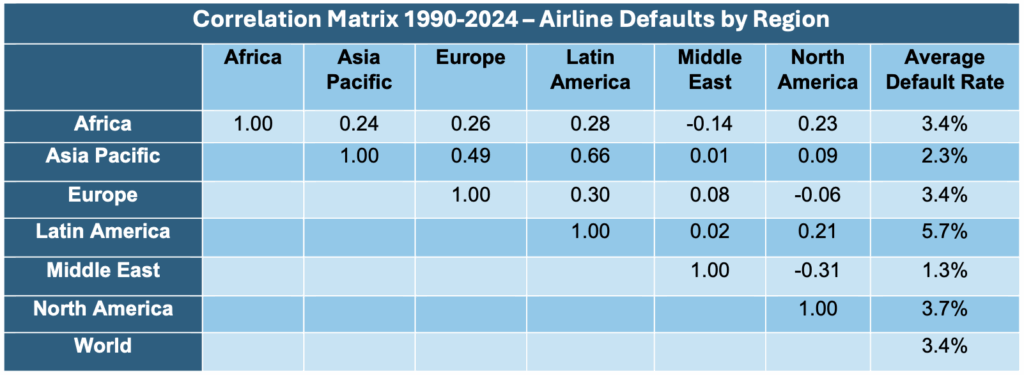

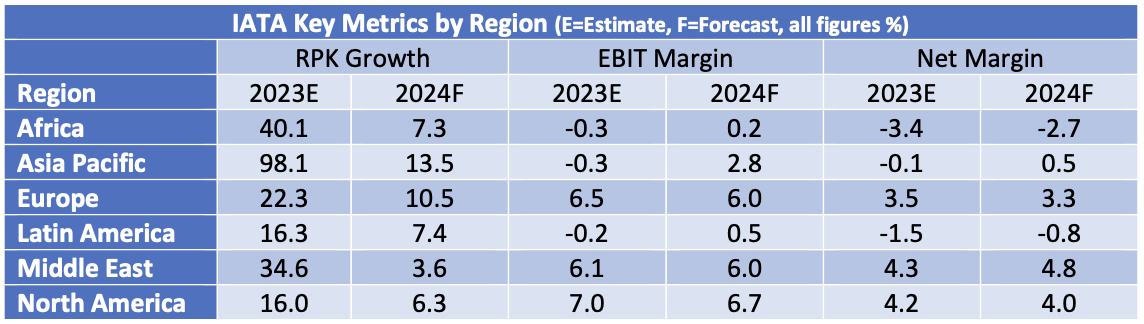

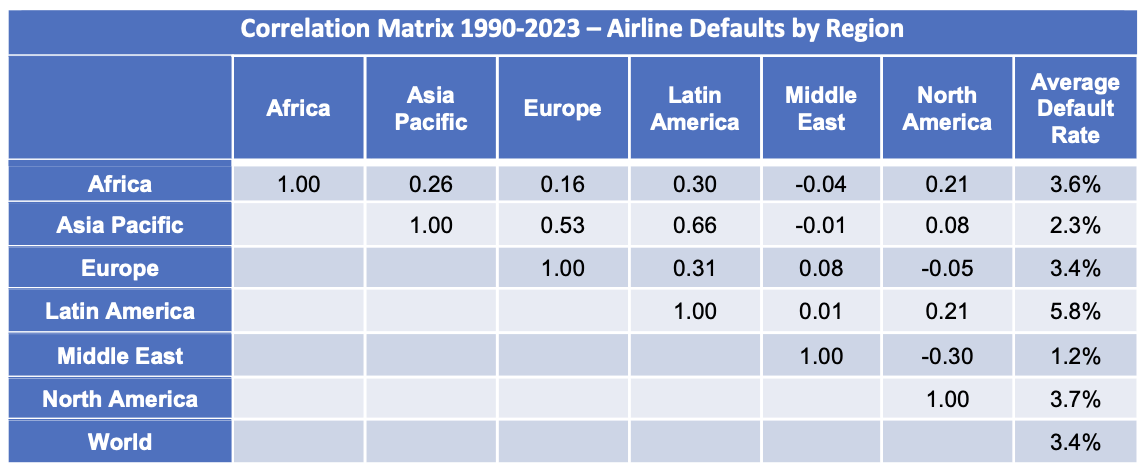

Another significant and related result is that default rates by region are not strongly correlated as can be seen in the table below. This should not really be surprising as analysis of traffic growth and airline profits by region shows a similar pattern.

We believe this lack of correlation is a key explanation of how most aircraft lessors are financially robust across the cycle despite serving a single relatively risky industry. 2024’s experience in terms of defaults by aircraft is an example how defaults are often skewed by region.

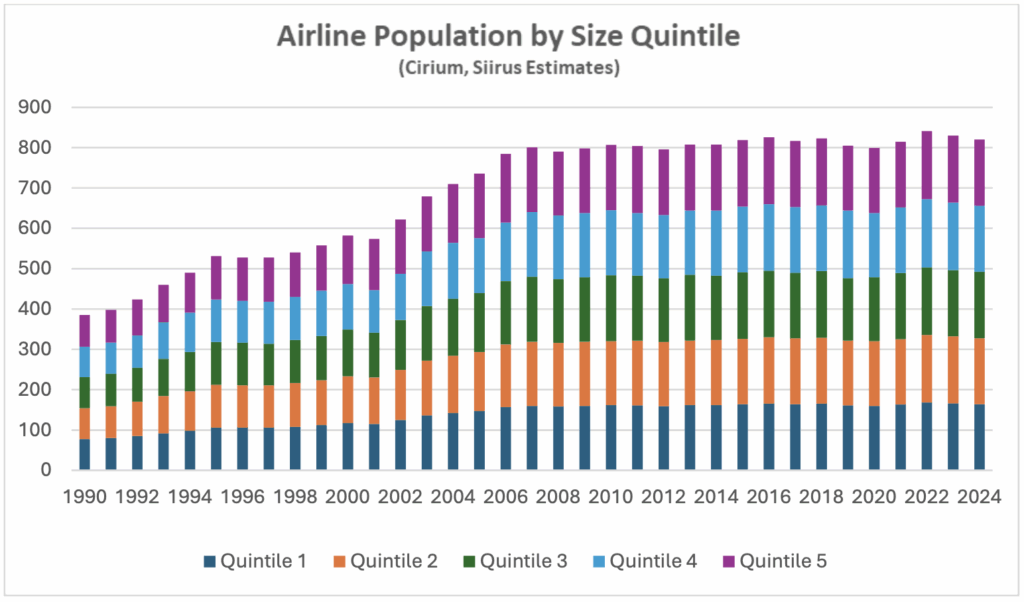

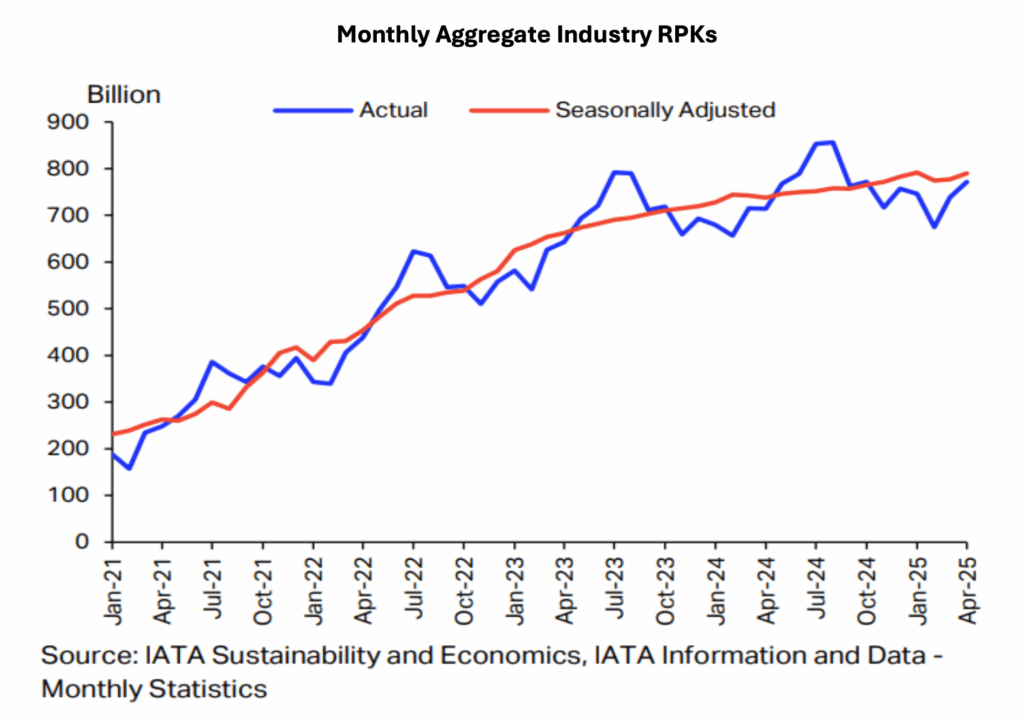

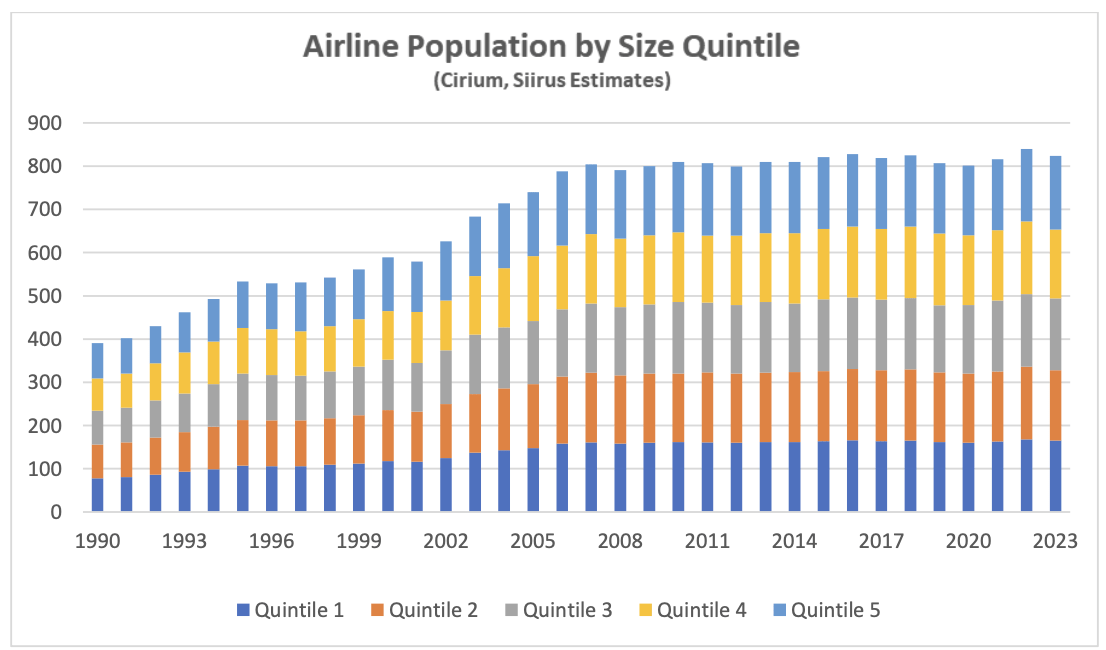

We also try to see what impact airline size has had on default rates. To do this we divide airlines into quintiles based on size as measured by number of seats, with each quintile representing roughly the same number of airlines. The chart below shows the population of airlines by quintile which has been quite stable since the late 2000s. During this period, bigger airlines have grown faster than smaller airlines resulting in a more concentrated industry.

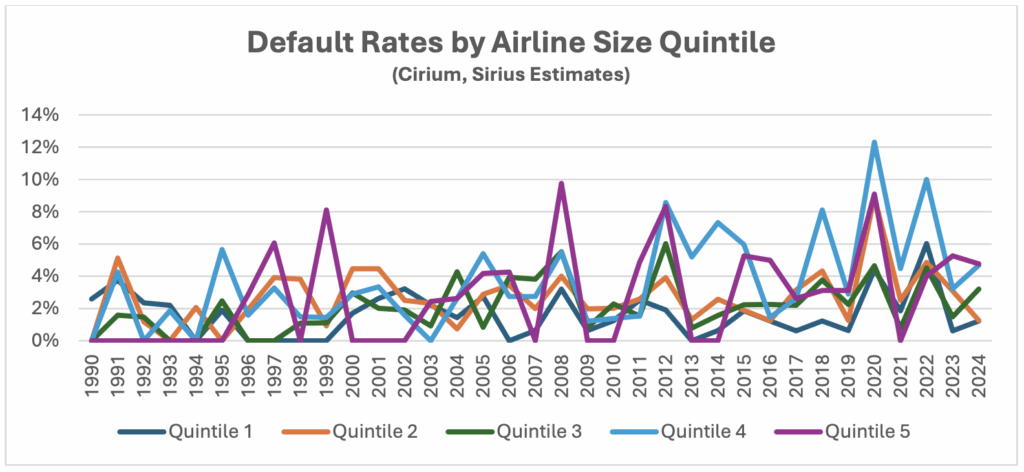

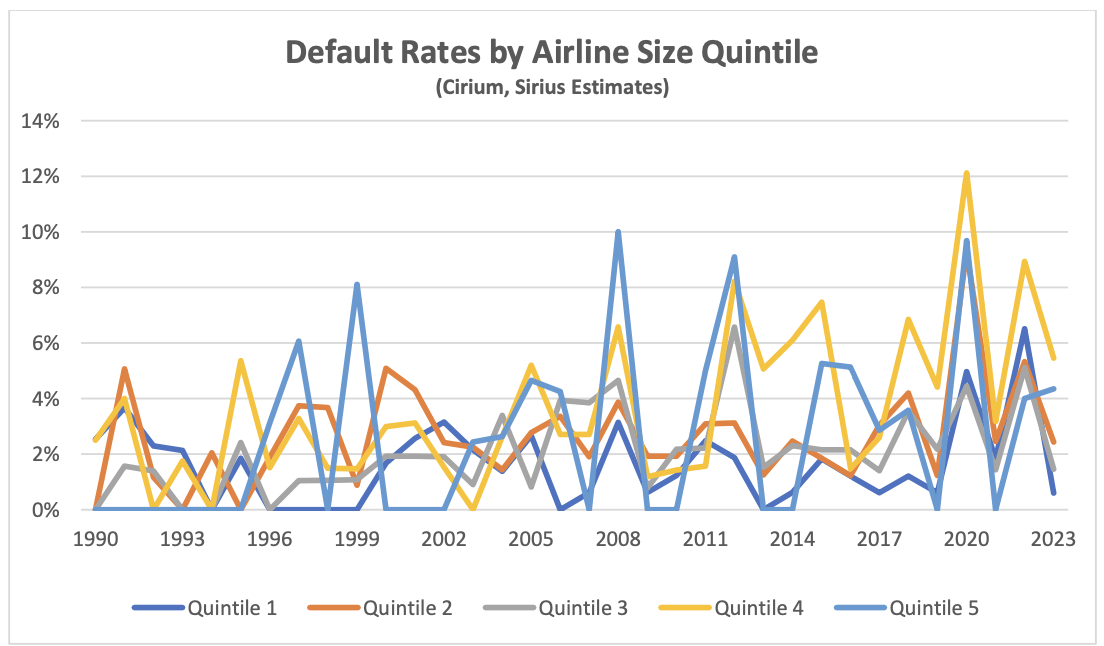

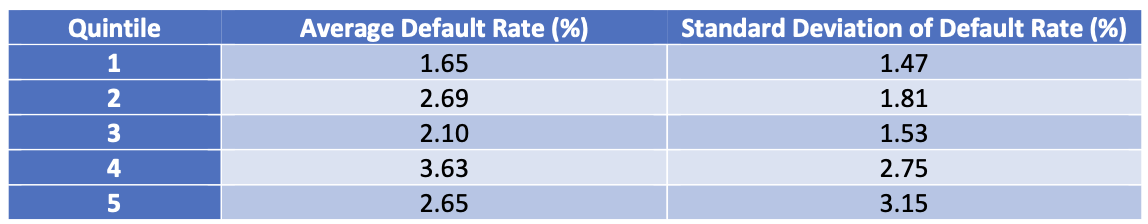

The default rates by quintile as presented in the chart below are visually confusing but the numbers in the following table help to put some structure around the results.

The table shows that the biggest airlines have the lowest and least volatile default level – volatility matters because it is harder to manage a default rate that is “spiky”. Once we go to the other quintiles there is no observable relationship between size and default rate, but there is a definite upward trend in volatility as airlines become smaller. Overall, our analysis suggest size has a limited influence on creditworthiness, and it would be wrong to assume that the lower default rate for larger airlines makes them “investment-grade” by a flawed analogy with credit ratings. The airlines in Quintile 1 have a default rate of 1.7% vs 3.4% for all airlines – for purposes of comparison the average default rate for S&P investment-grade bond issuers was 0.1% p.a. vs 3.9% p.a. for speculative-grade for the same period.

It’s also worth considering whether a broader data set might have implications for how the rating agencies look at the credit status of the airline industry. Although the universe of airlines with public ratings is small, the rating agencies conduct a lot of private ratings as part of rating aircraft ABS transactions. Although these private ratings remain confidential, general feedback is typically that average credit ratings for the airlines in these portfolios is “high B/low BB” i.e. middling speculative grade.

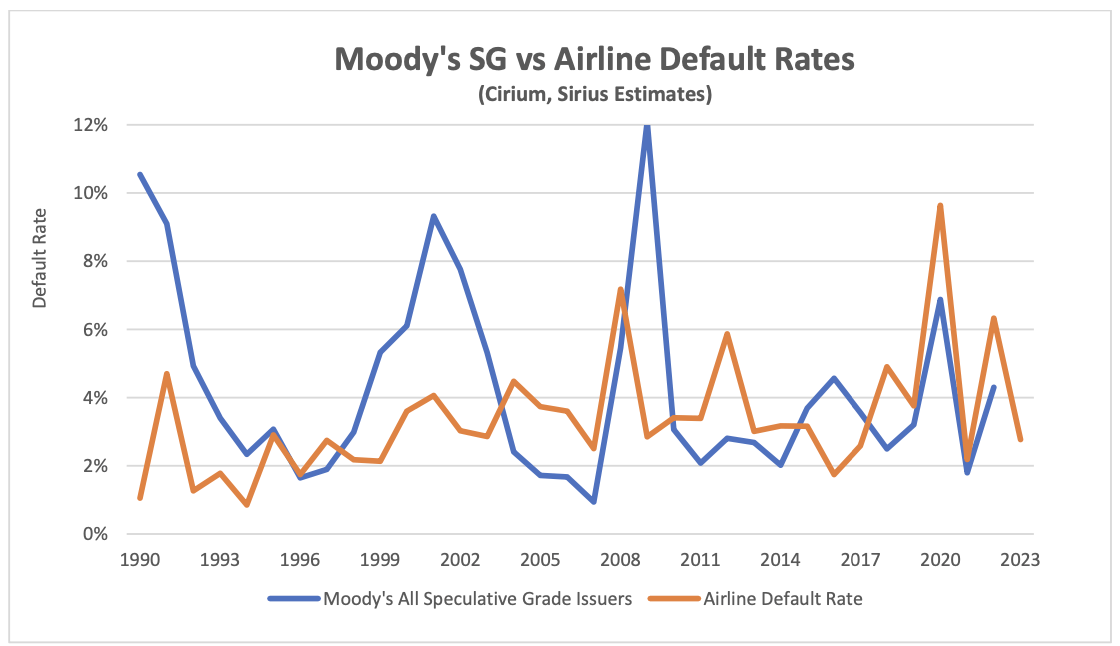

A comparison of our estimated airline default rate with the default rate for all bond issuers rated speculative grade by S&P shows airlines with both a lower default rate (3.4% p.a. vs 3.9% p.a.) and lower volatility (1.7% standard deviation vs 2.7%). It looks unlikely that the rating agencies are being overly optimistic about airline credit quality, but the most striking difference arises in volatility where it seems the benefit of geographical diversification more than offsets the benefit of industry diversification (we assume that the S&P issuer universe is concentrated in the US).

Qualifications and Conclusions

One should bear in mind that the nature of a lessor’s credit exposure to an airline is different to that of a bondholder because the lessor typically has the benefit of asset ownership and a lease security package that may include cash security deposits, letters of credit and other features. This has allowed lessors to grant significant forbearance to airlines at various other times as well during the pandemic.

Despite these limitations on making fair comparisons between our airline default estimates and historic bond defaults we believe these results are striking none the less, particularly on the positive benefits of geographic diversification, the limitations of size effects and the lower volatility of airline defaults compared to speculative grade bond issuers.

Regular Topics

Macro-Economic Background

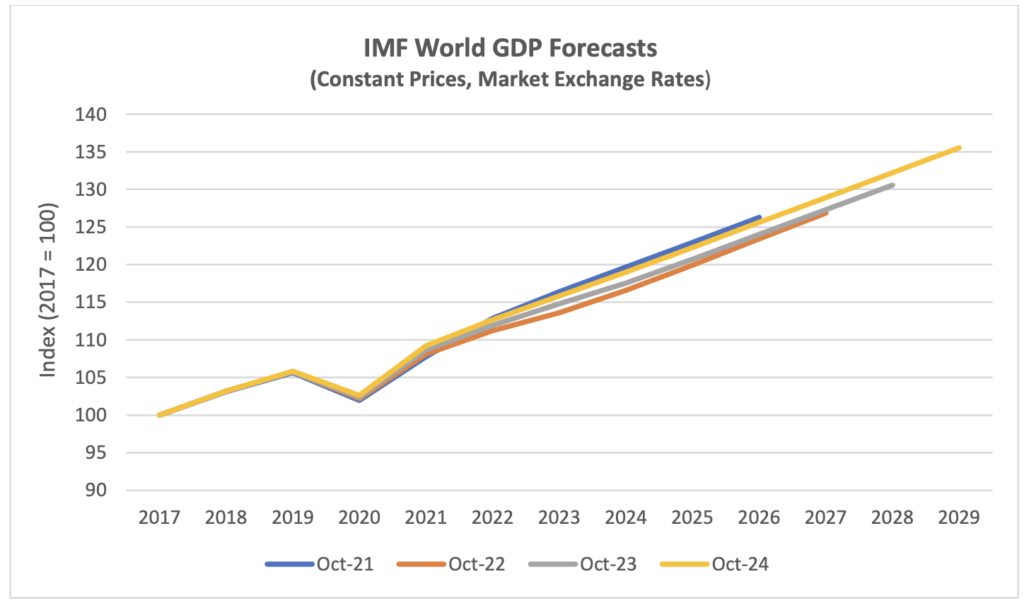

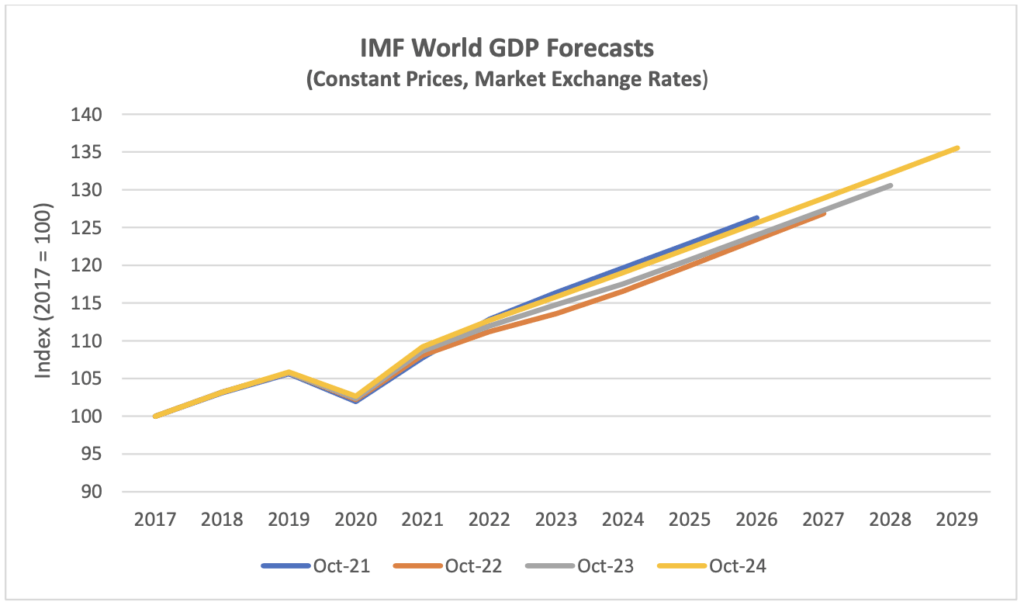

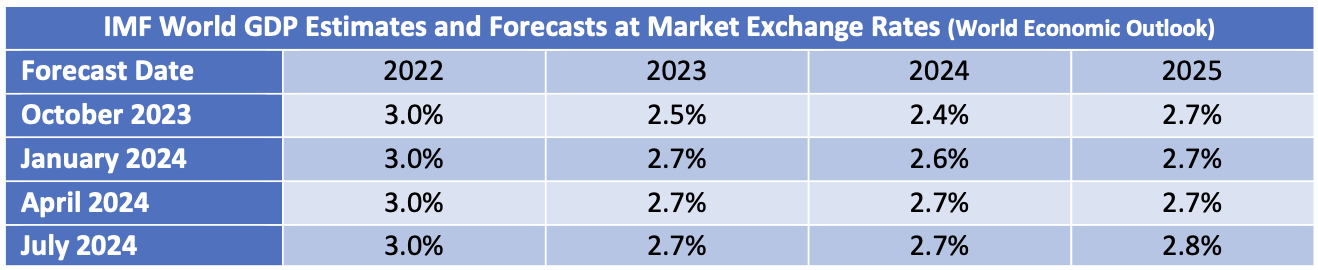

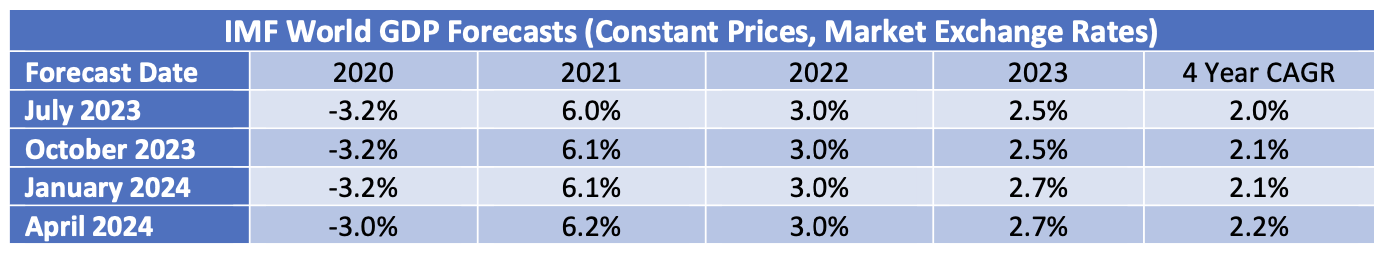

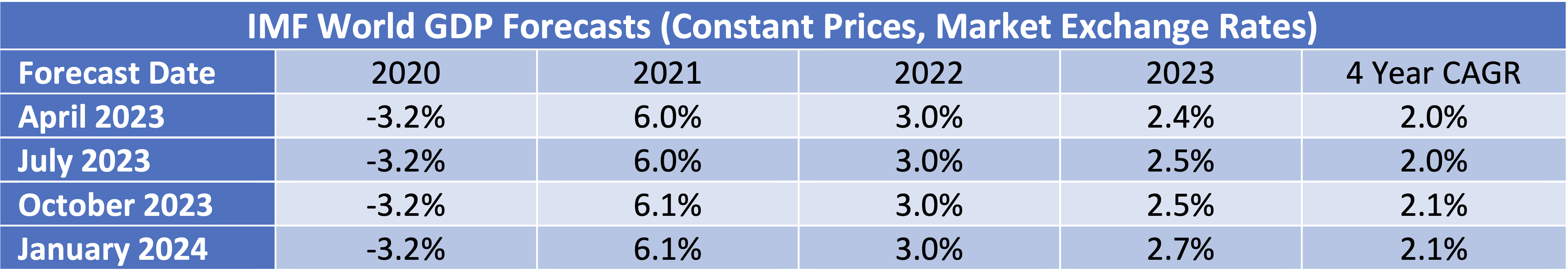

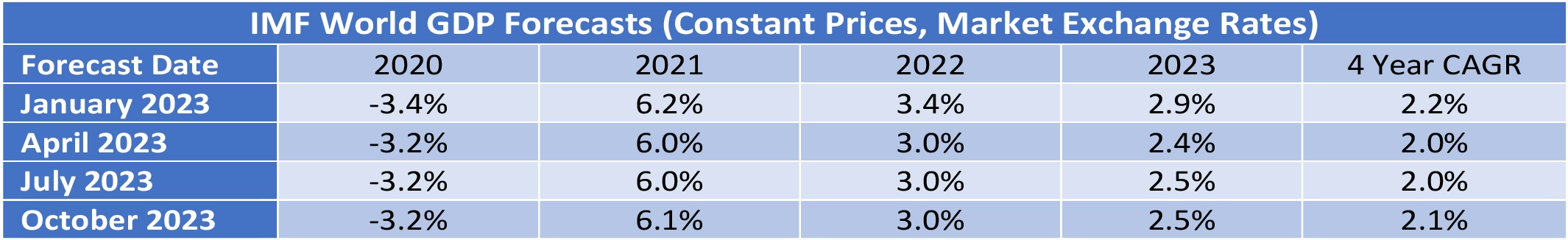

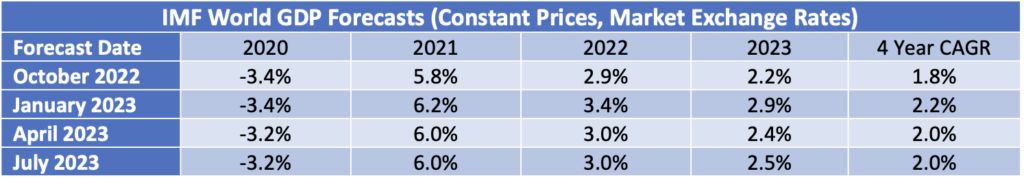

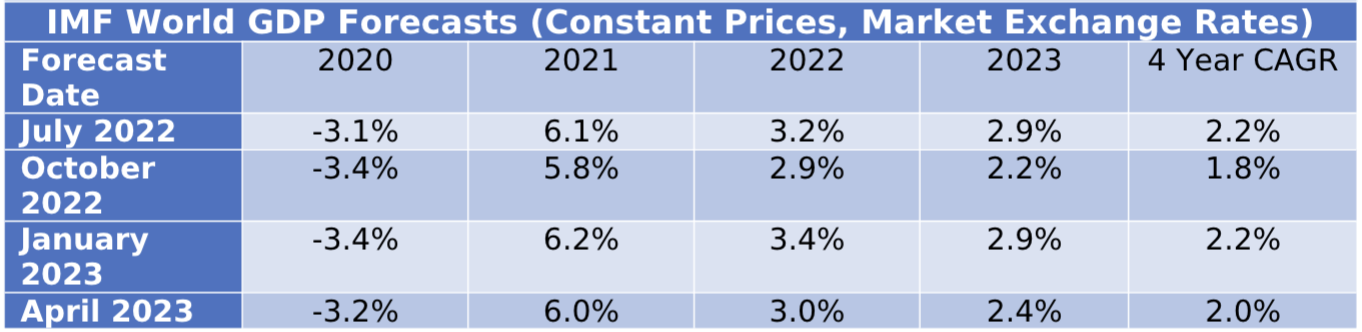

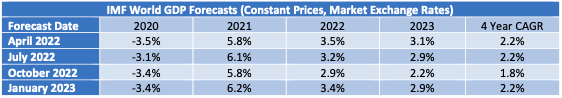

Despite the “trade wars” initiated by the US this year the IMF has not materially changed its World GDP forecast in its latest World Economic Outlook published in April, and its first forecast for 2030 shows a similar level of growth to prior years.

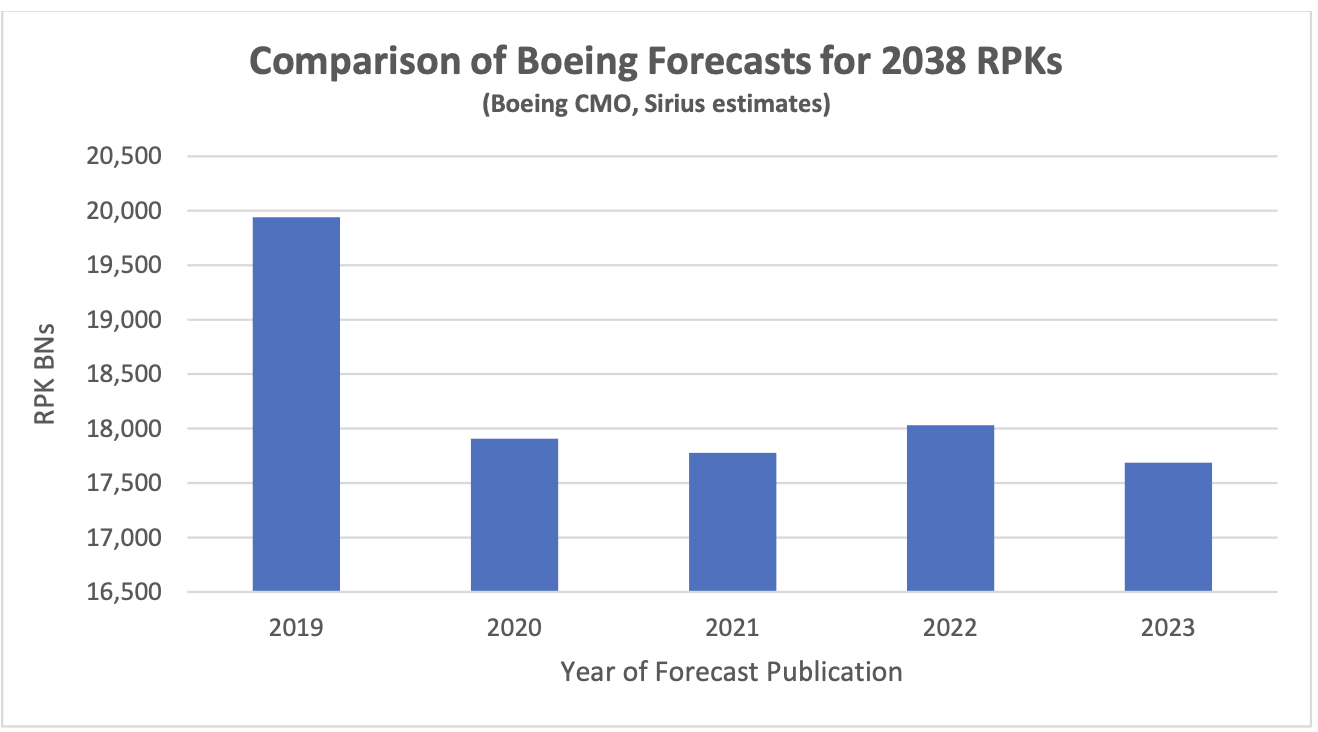

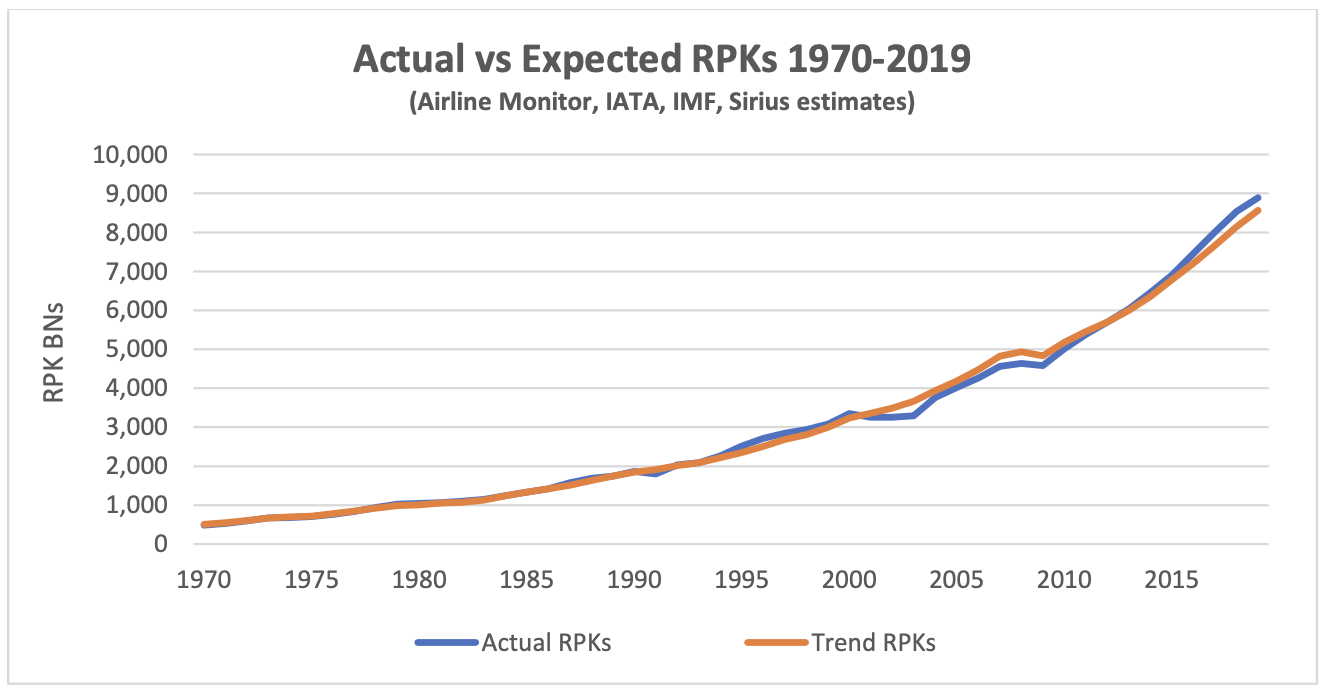

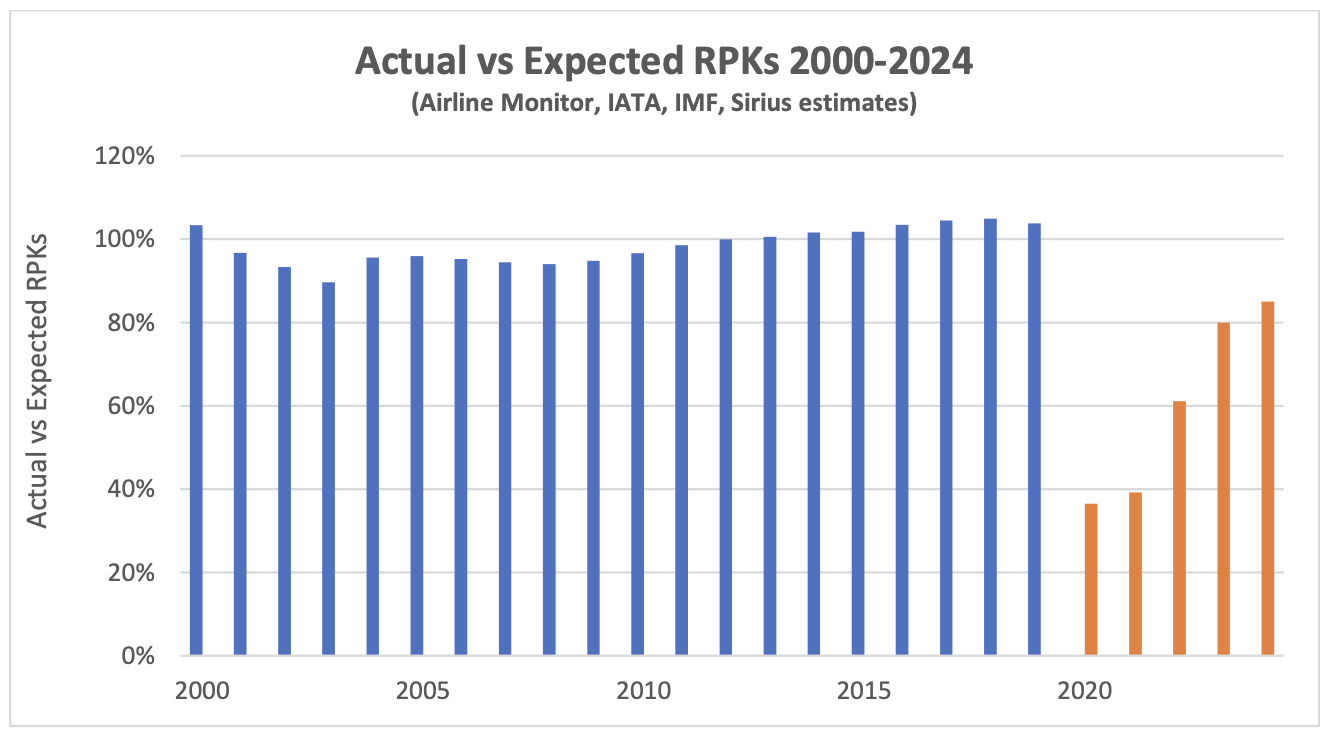

Economic growth is a key driver of long-term growth of air travel. However, since early 2020 its impact has been overshadowed by the fall and recovery in traffic associated with the pandemic. In time the influence of overall economic conditions on air travel is likely to reassert itself, but industry forecasts published by Airbus, Boeing and IATA assume much higher rates of traffic growth than GDP growth over the rest of the 2020s as the former catches up to its long-term trend (see our Q1 2024 Industry Update for a more detailed discussion).

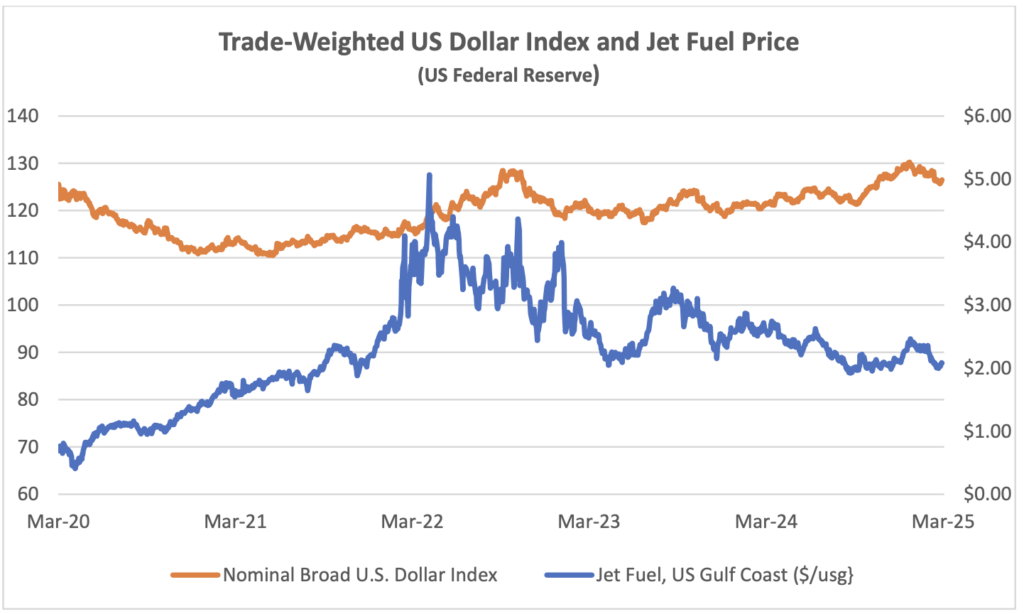

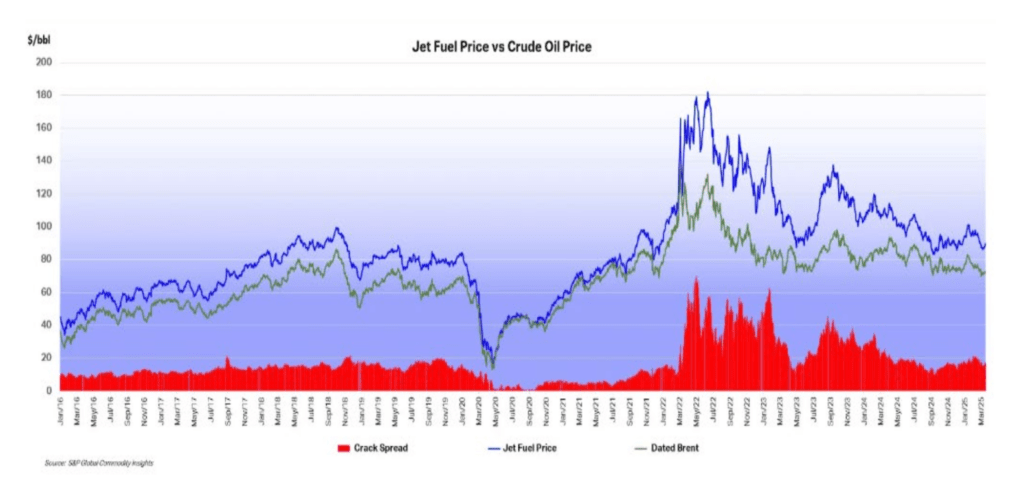

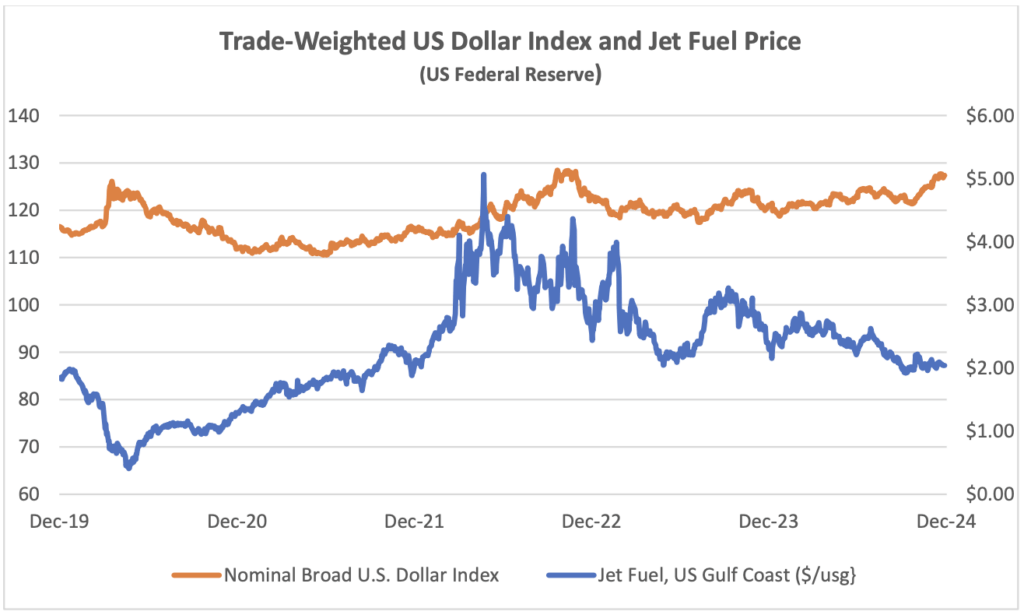

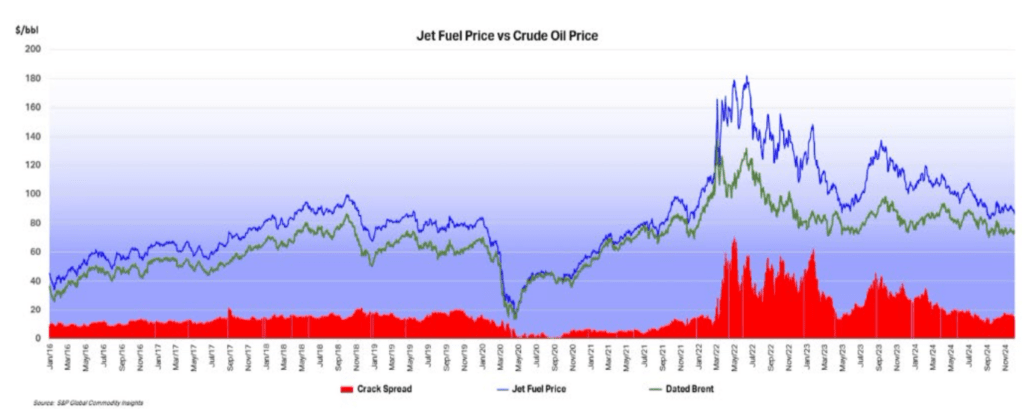

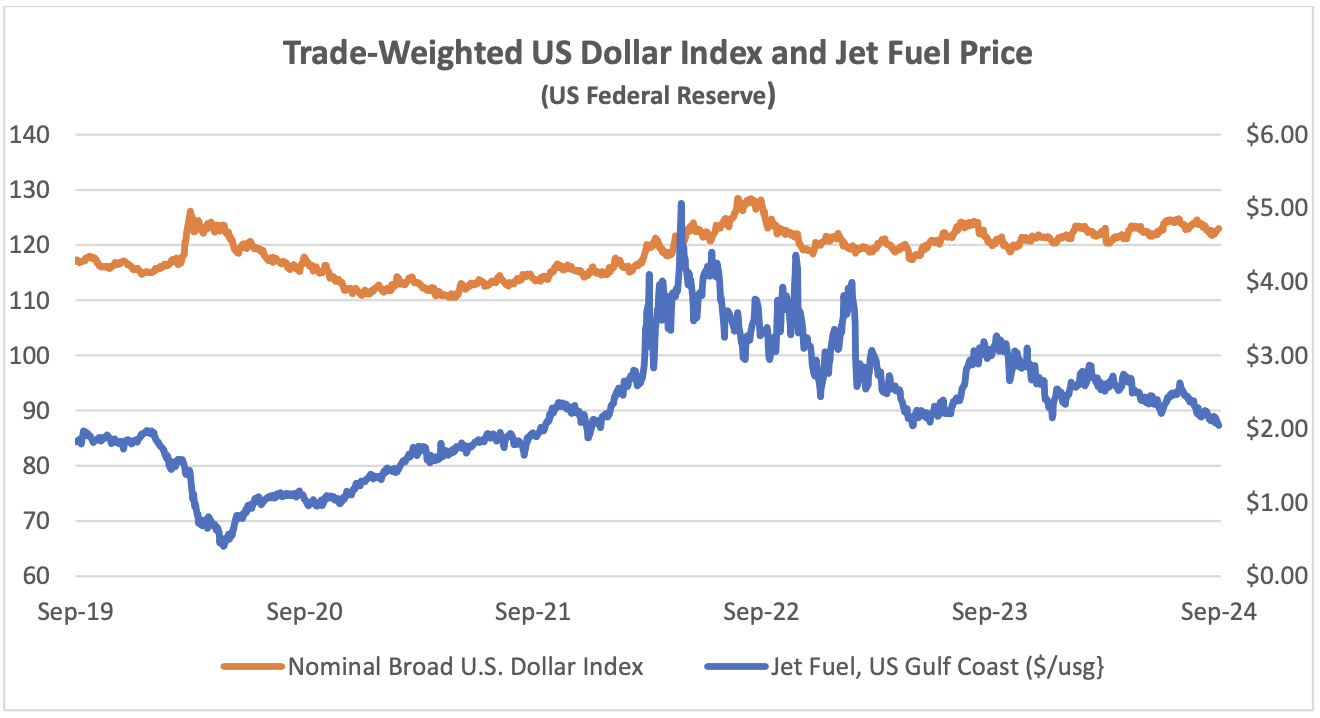

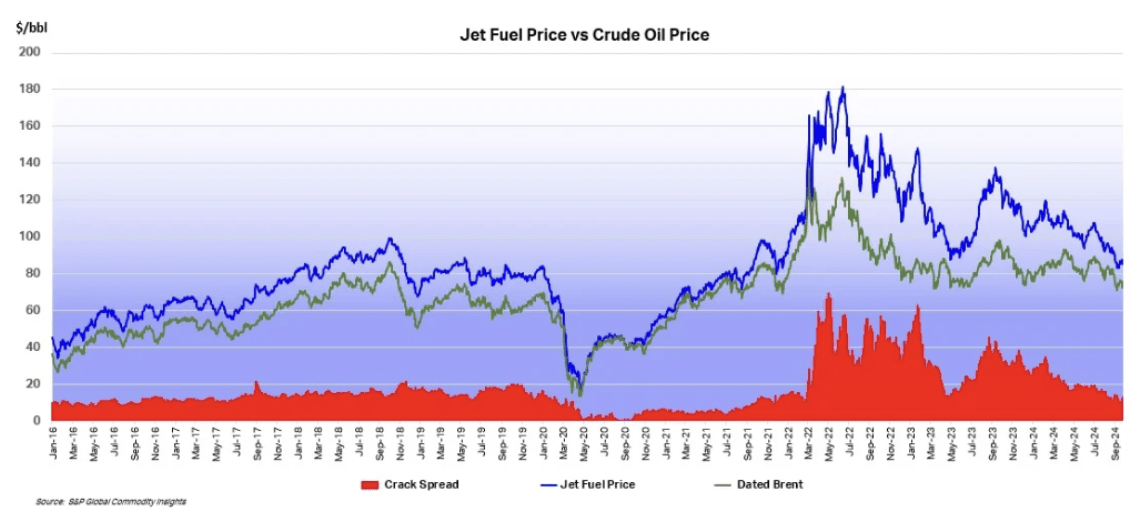

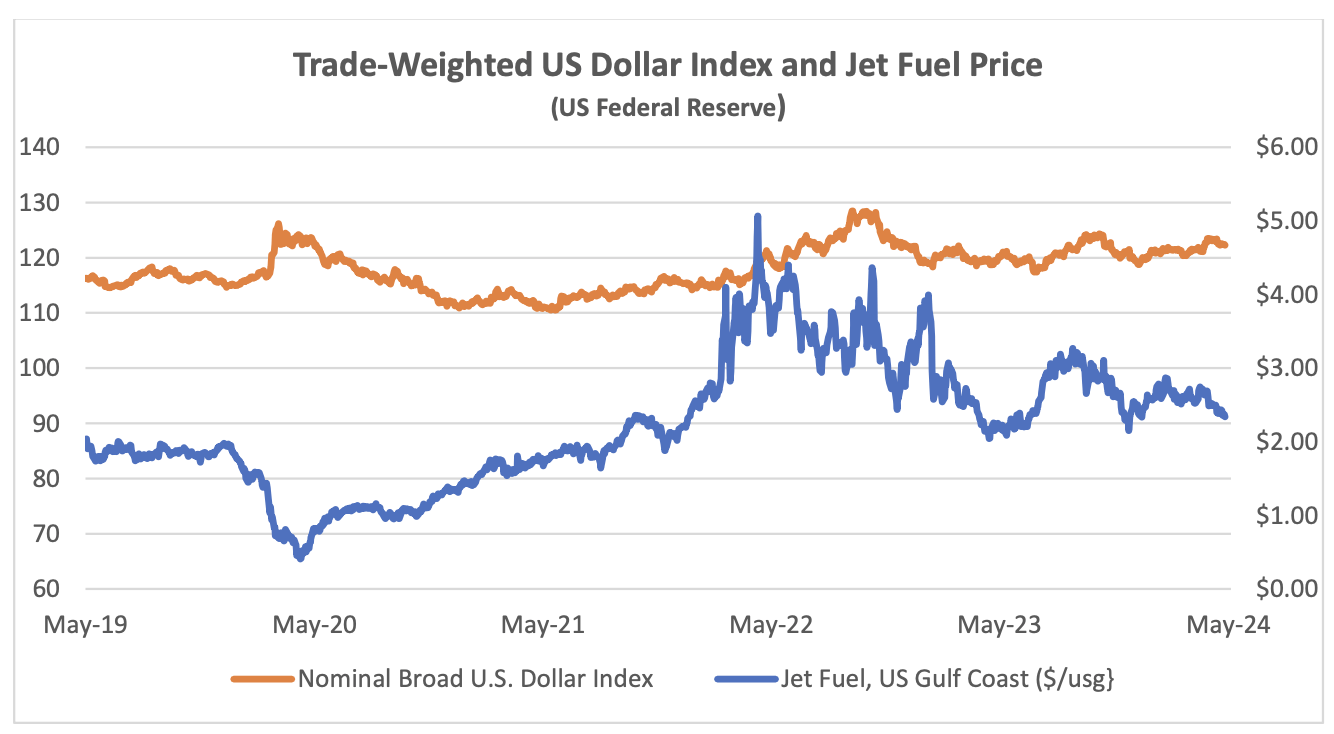

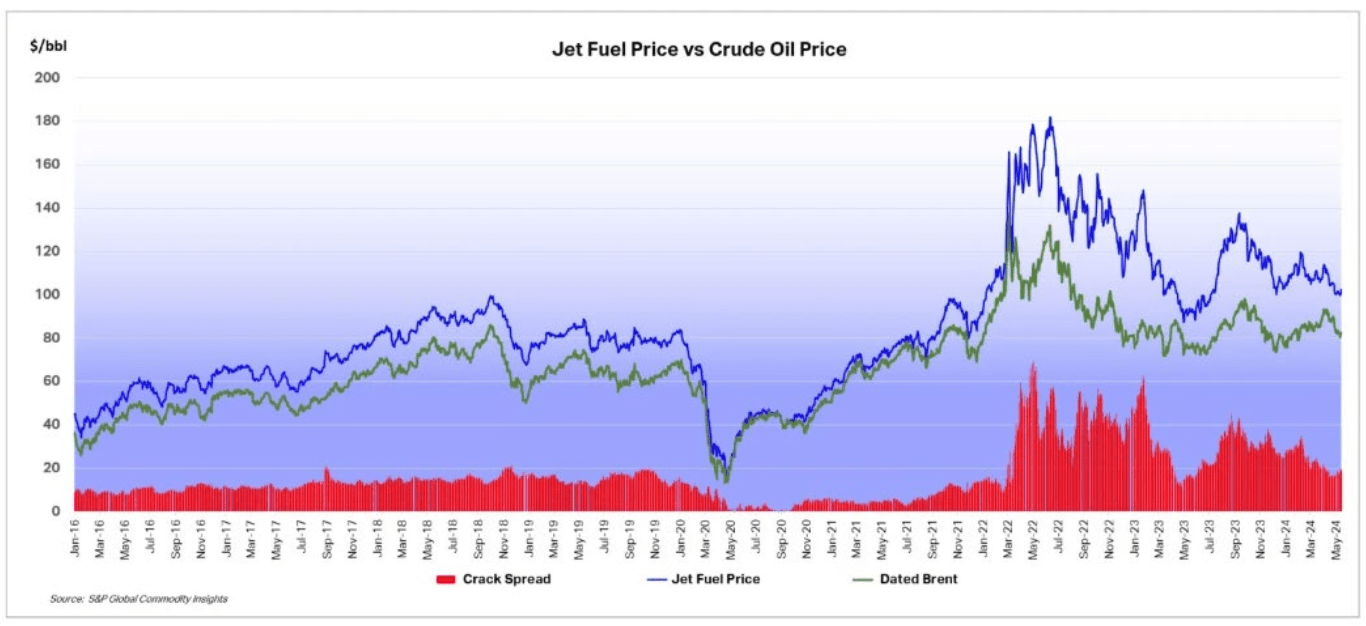

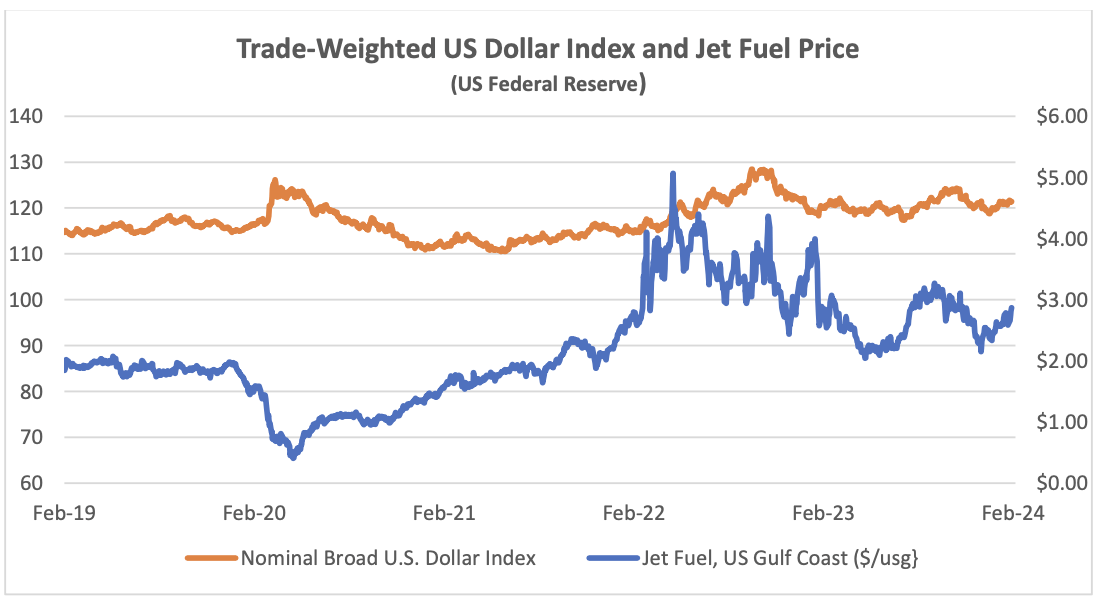

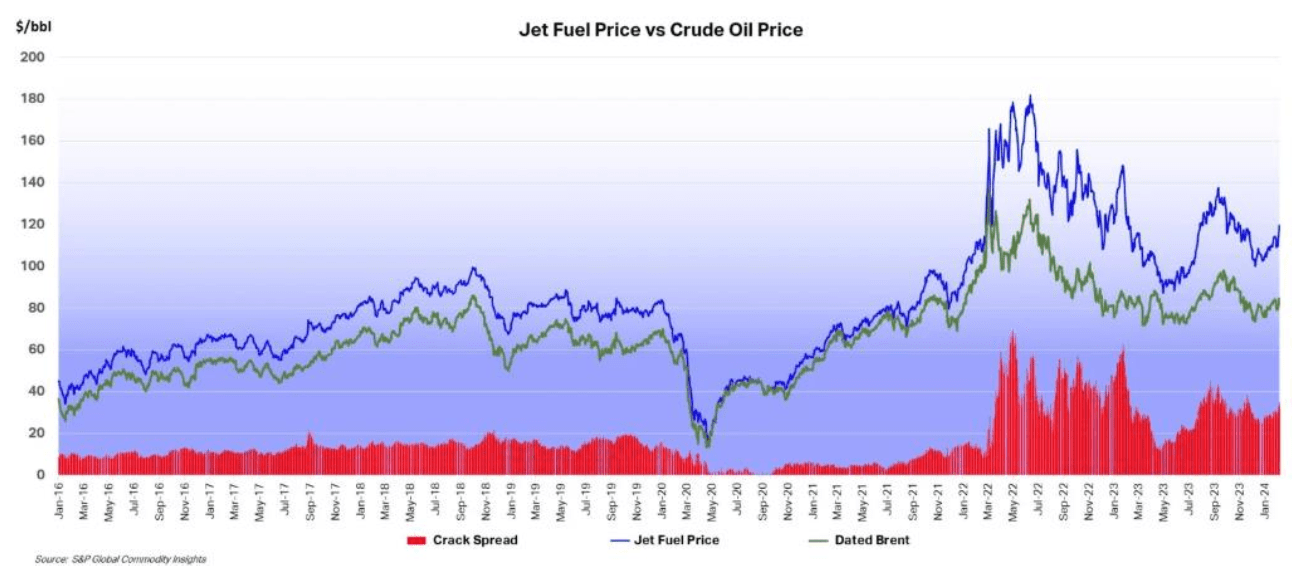

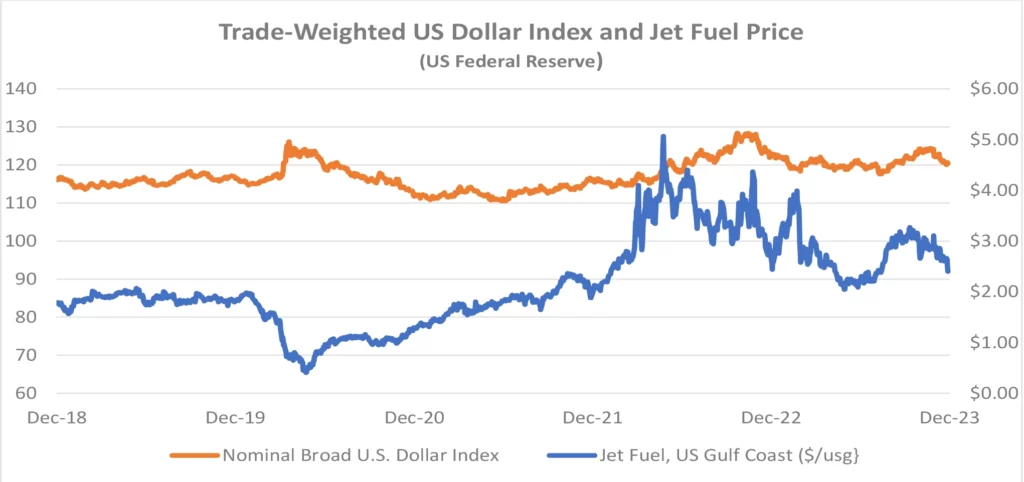

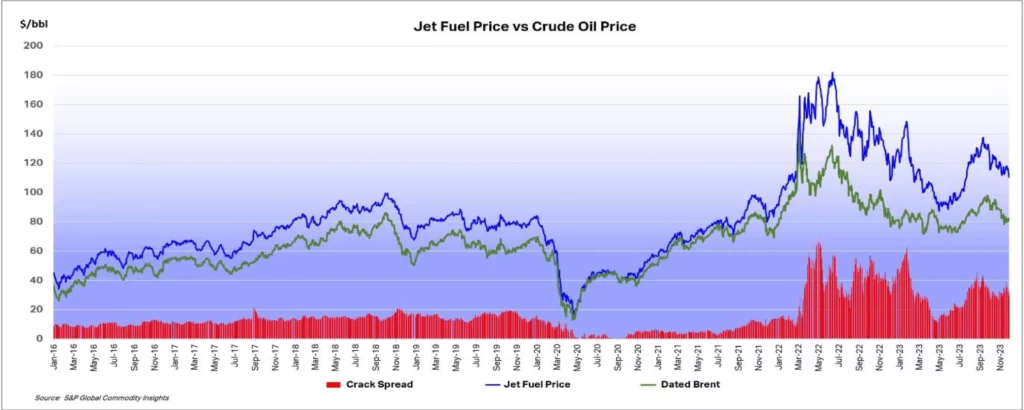

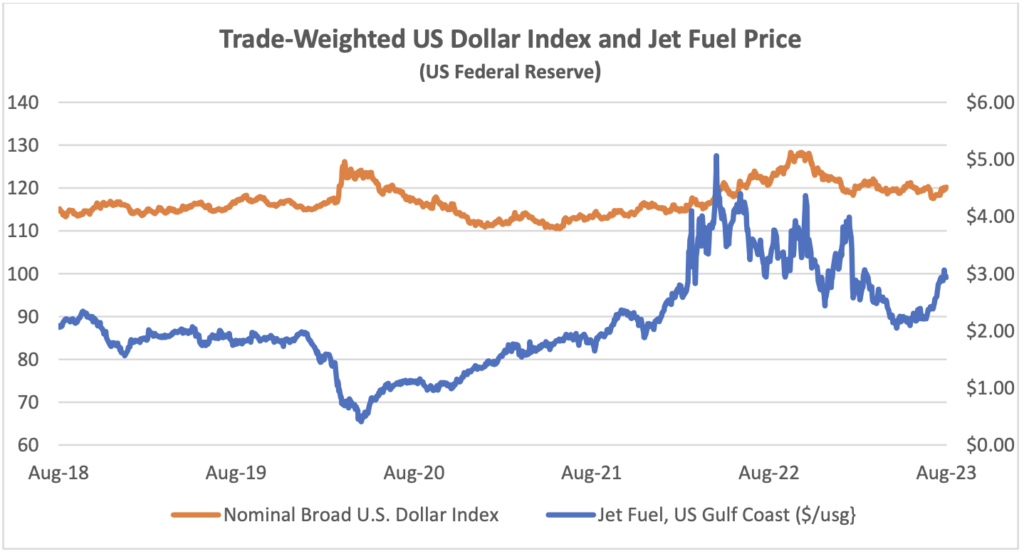

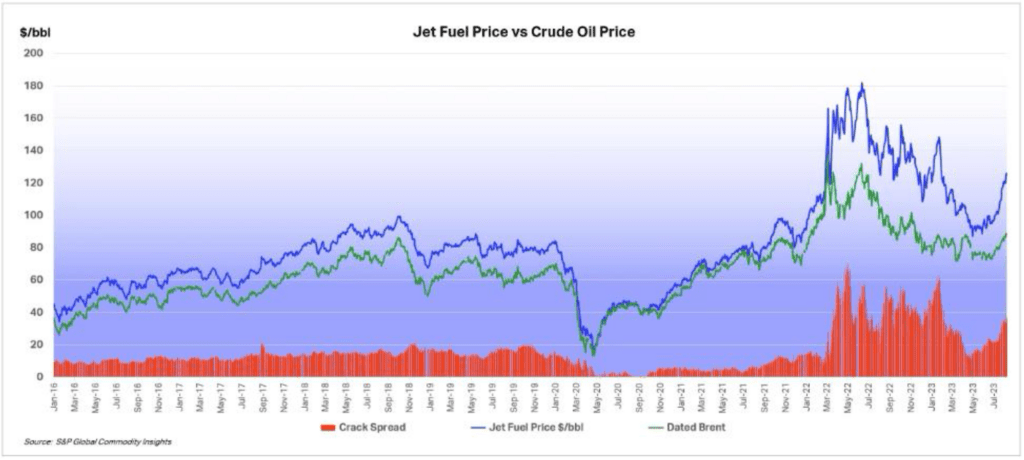

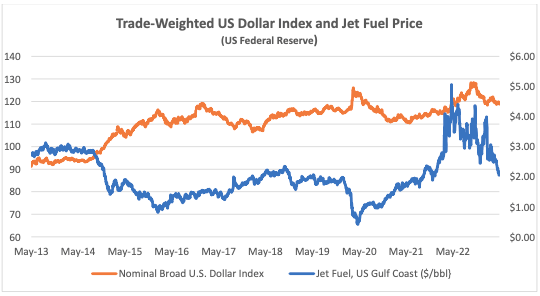

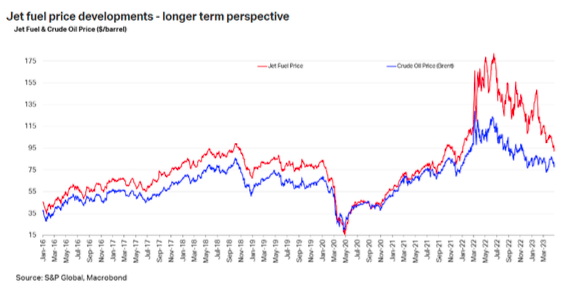

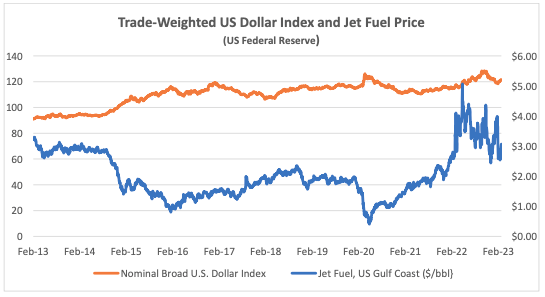

Two key macro variables have been moving in favour of the airline industry in recent months. The cost of jet fuel has fallen below $2.00 per gallon, mainly due to a fall in the price of crude oil as the crack spread remains quite high at c. $17 per barrel. IATA estimates that fuel accounted for 29% of total industry costs in 2024, and the current prices is 15% below the average for 2024 so this will be a very welcome change if sustained. There will probably be a lag for many airlines in seeing the impact of cheaper fuel in their financial results as they will have hedged their costs forward for periods of up to around a year. The US Dollar has also weakened which also helps airlines outside the US for dollar-denominated costs such as fuel, aircraft rents and aircraft spares.

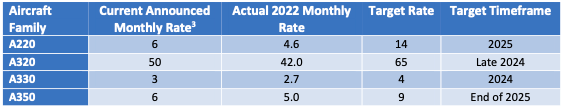

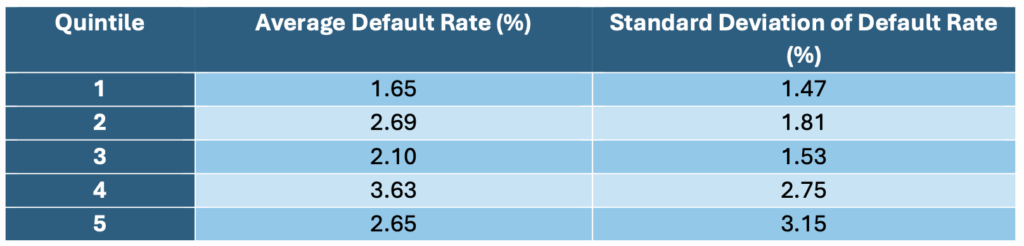

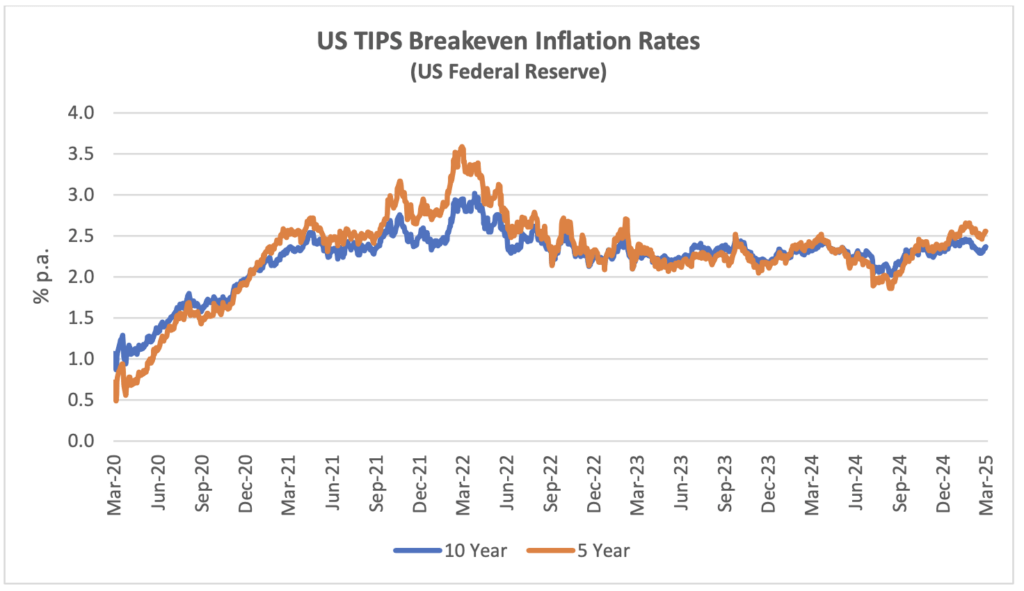

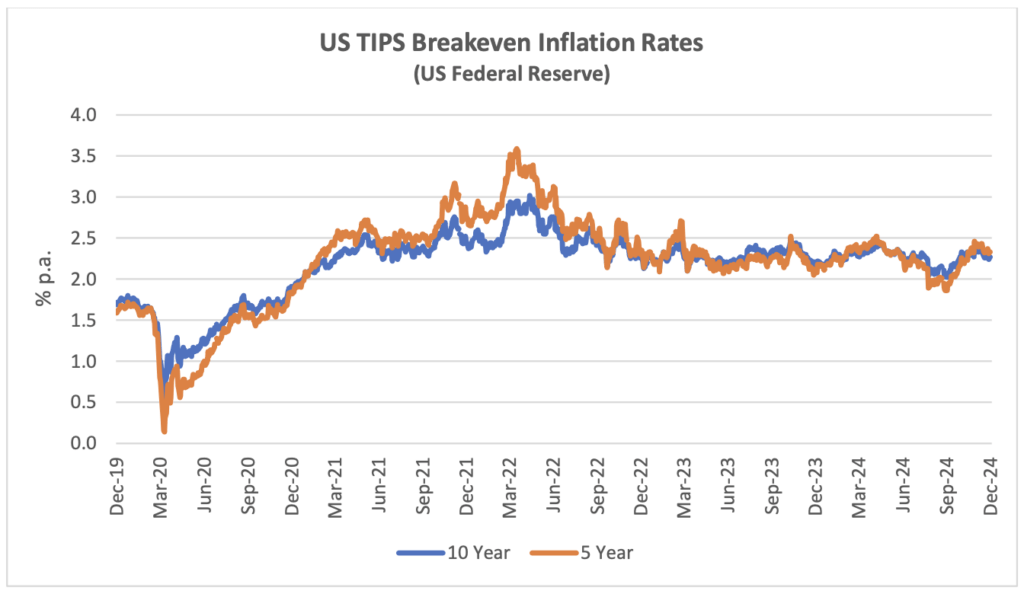

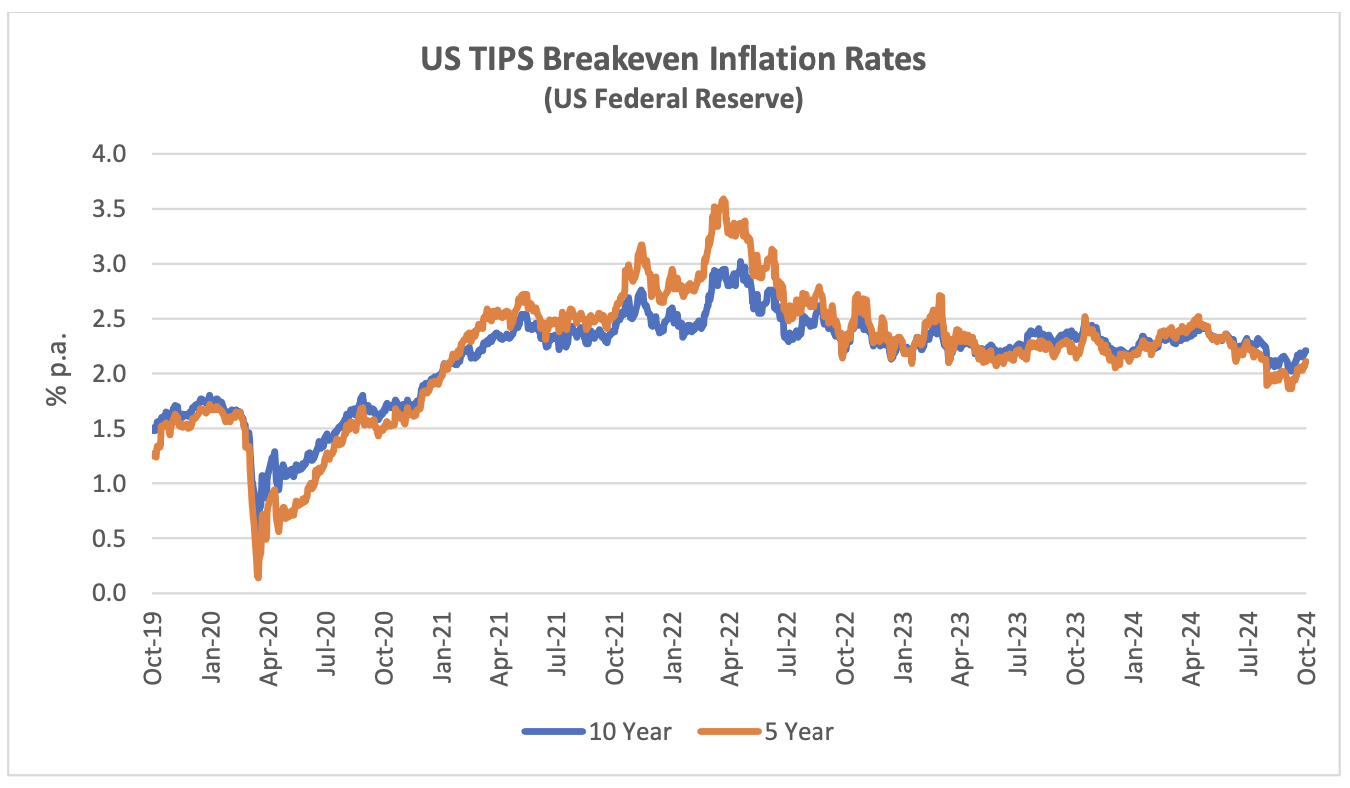

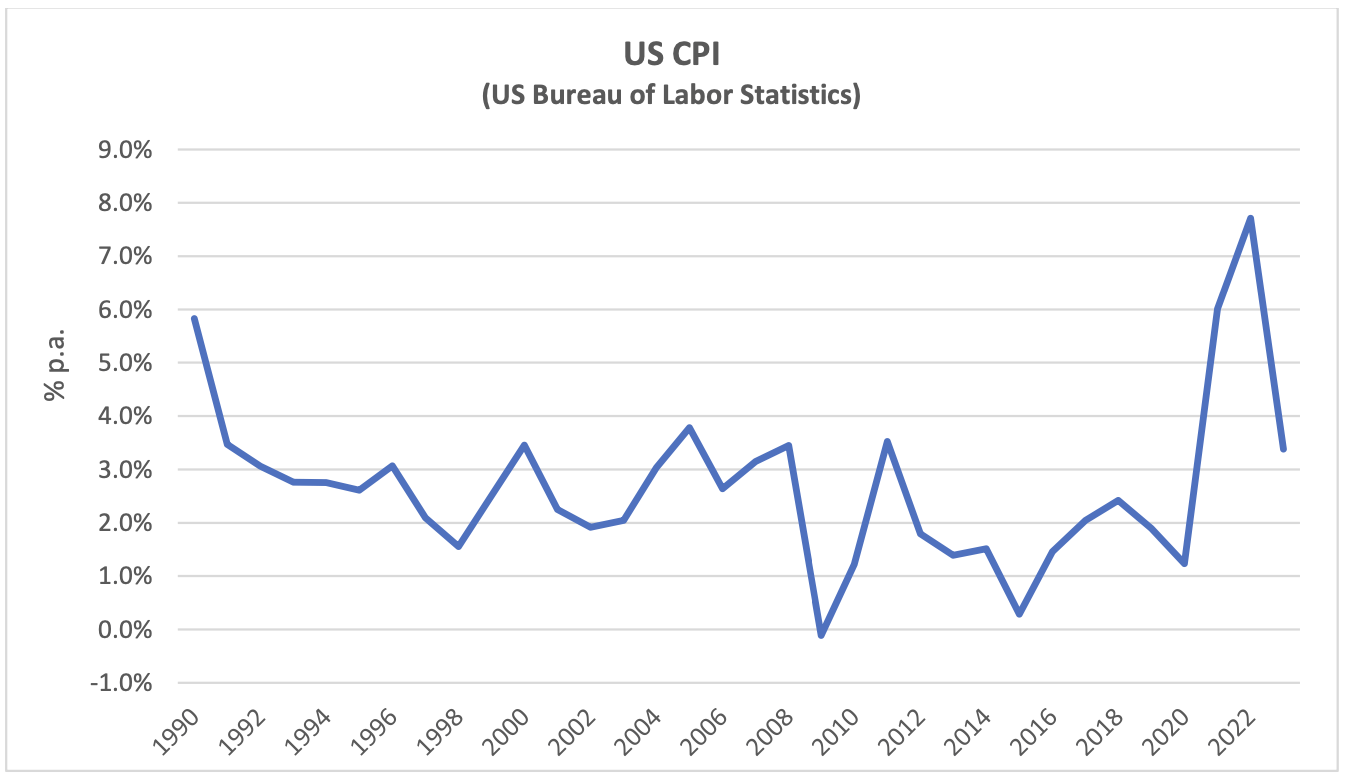

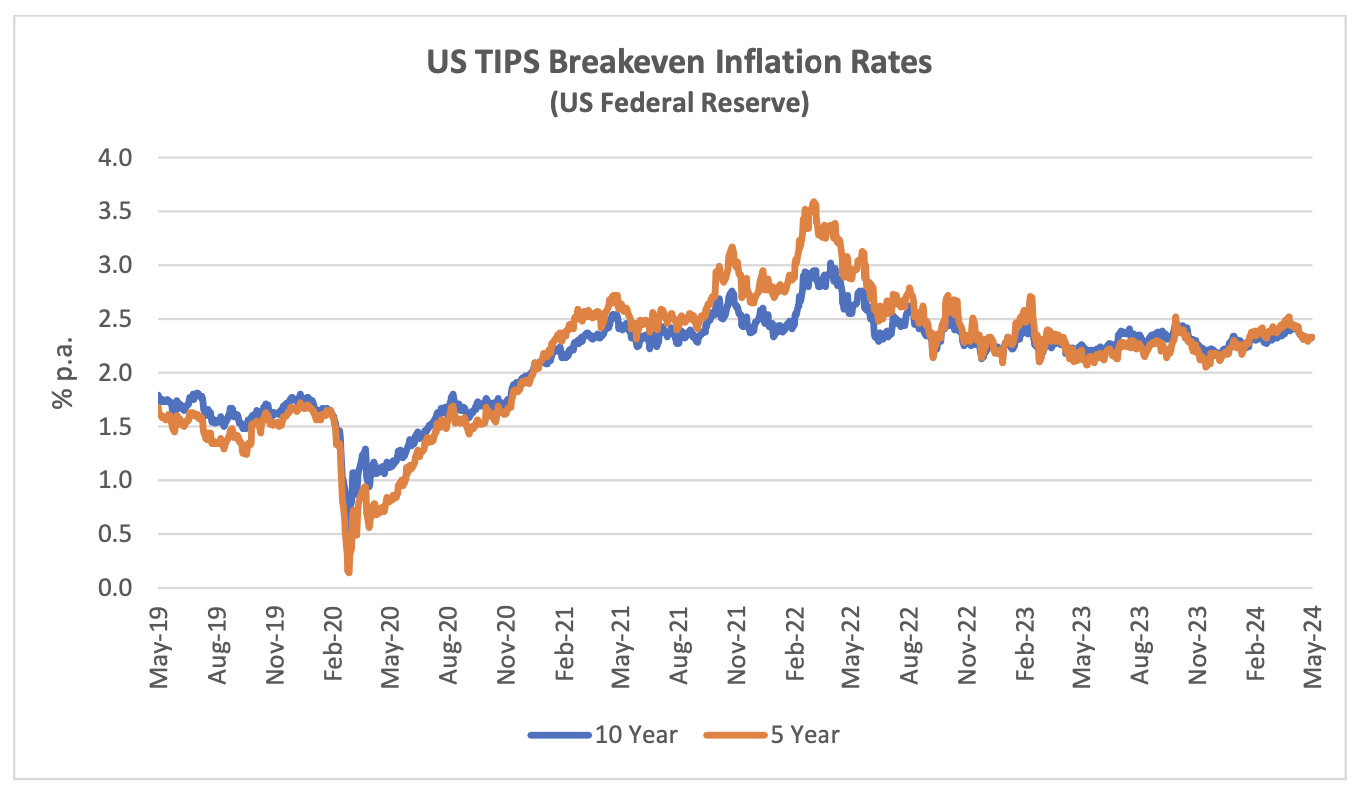

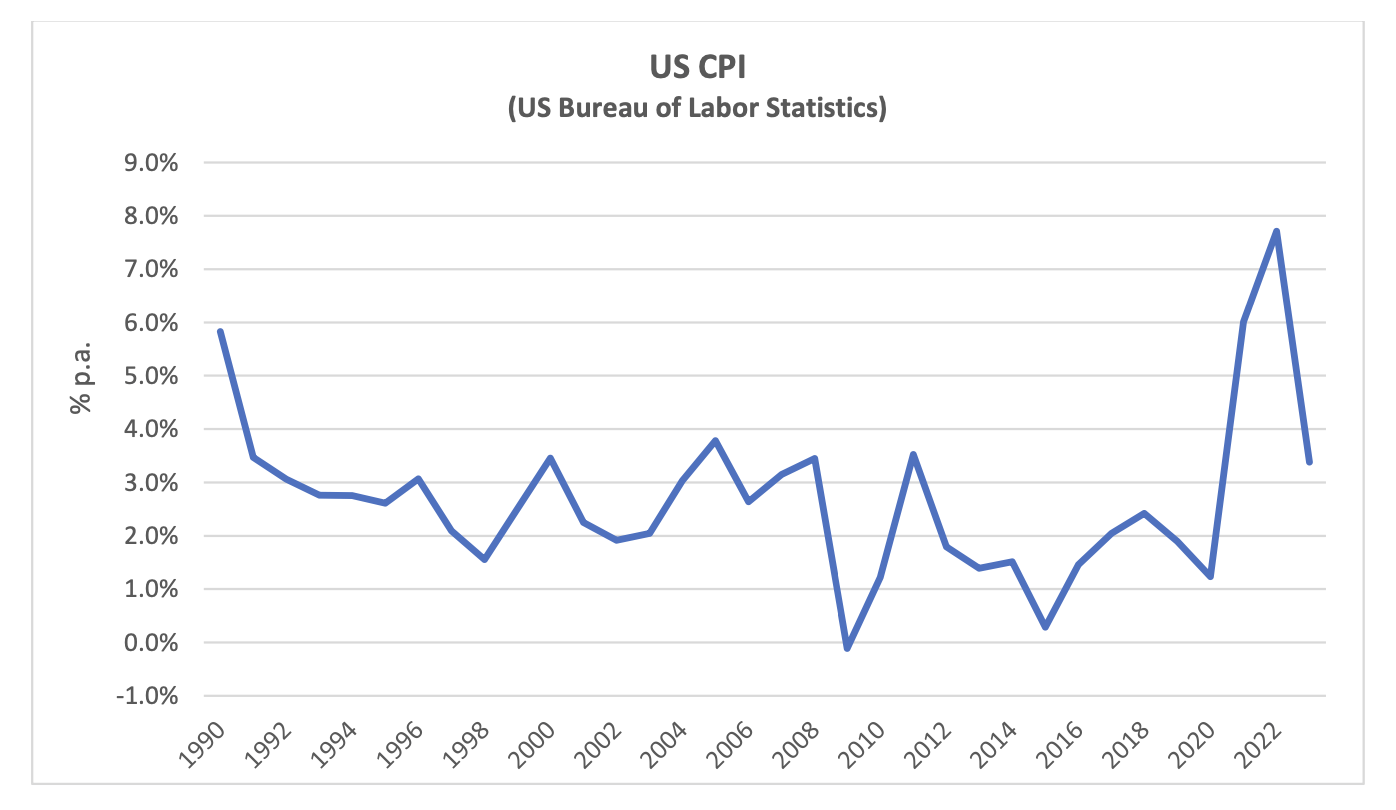

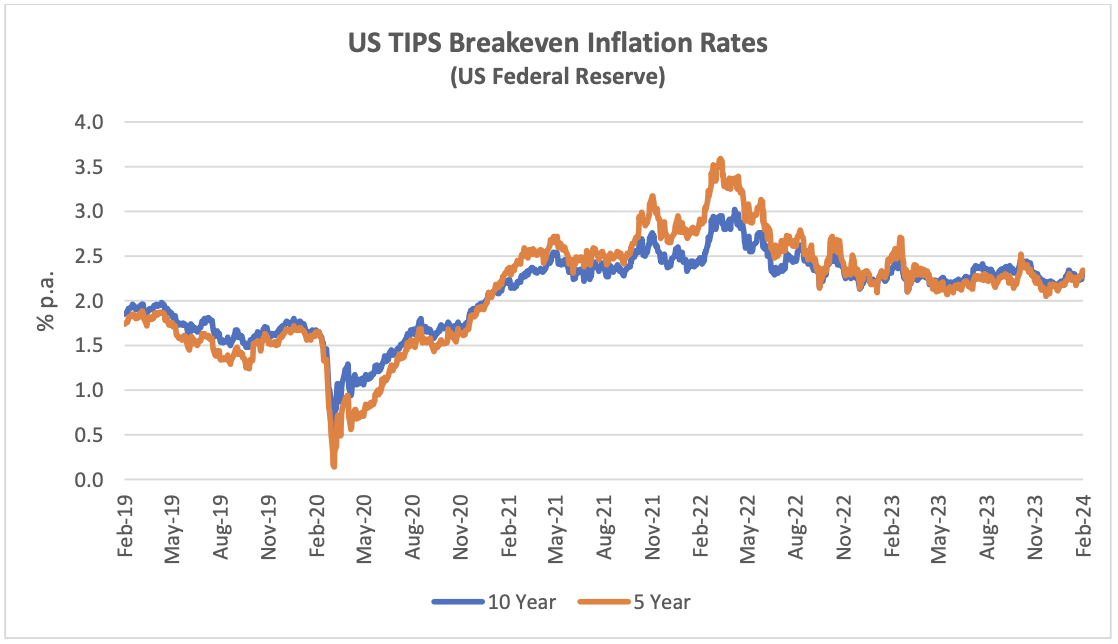

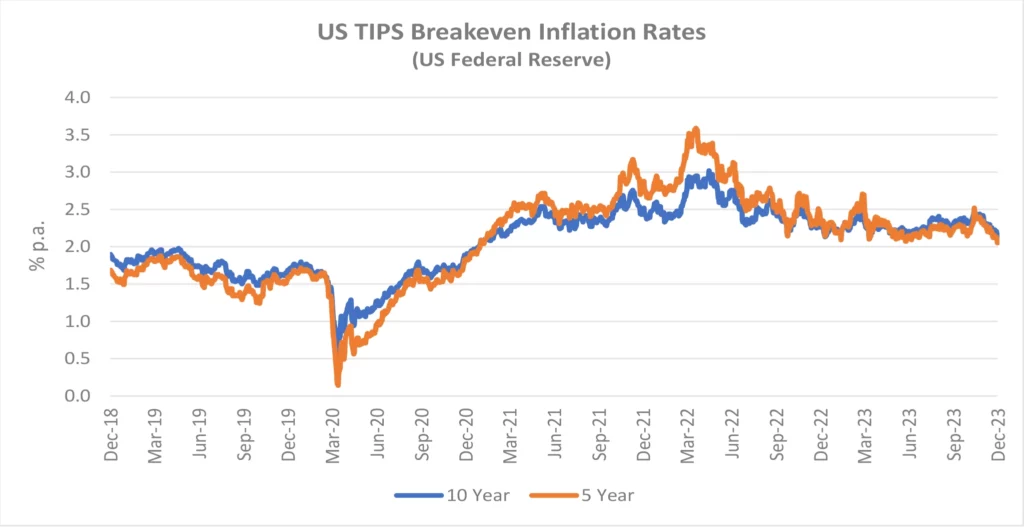

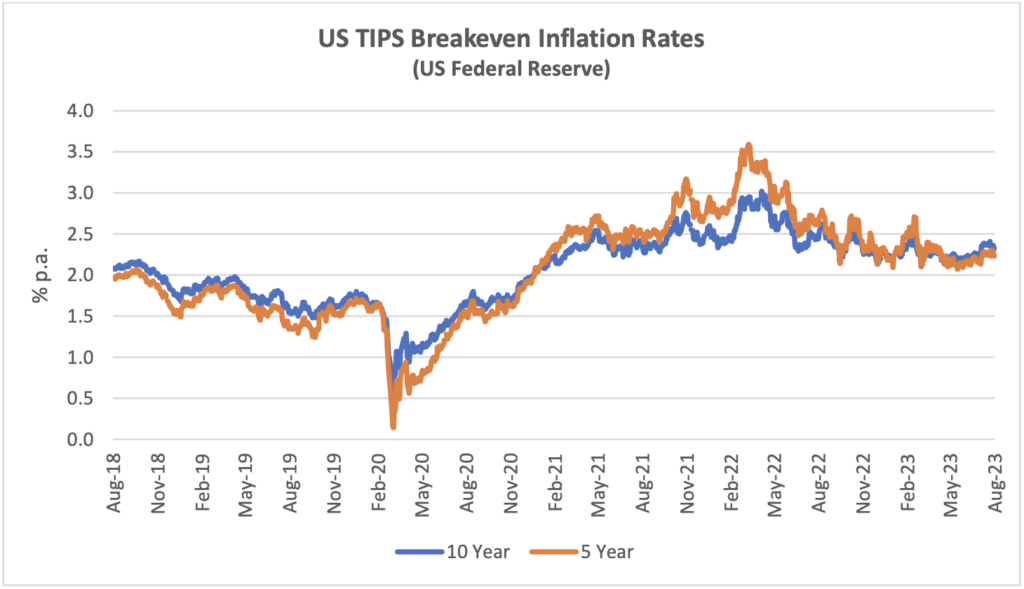

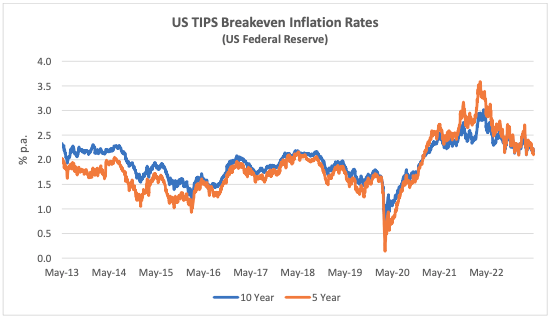

Another indicator that is potentially important to aircraft investors is the breakeven inflation rate on US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). This indicator measures inflation expectations and it matters because used aircraft values are strongly influenced by the cost of new aircraft and over time this cost is linked to US Dollar inflation. In the short term this linkage is driven by escalation clauses in aircraft purchase contracts and in the long term by the general input cost environment for the aircraft manufacturers. The chart below compares the breakeven rate for 10-year and 5-year TIPS.

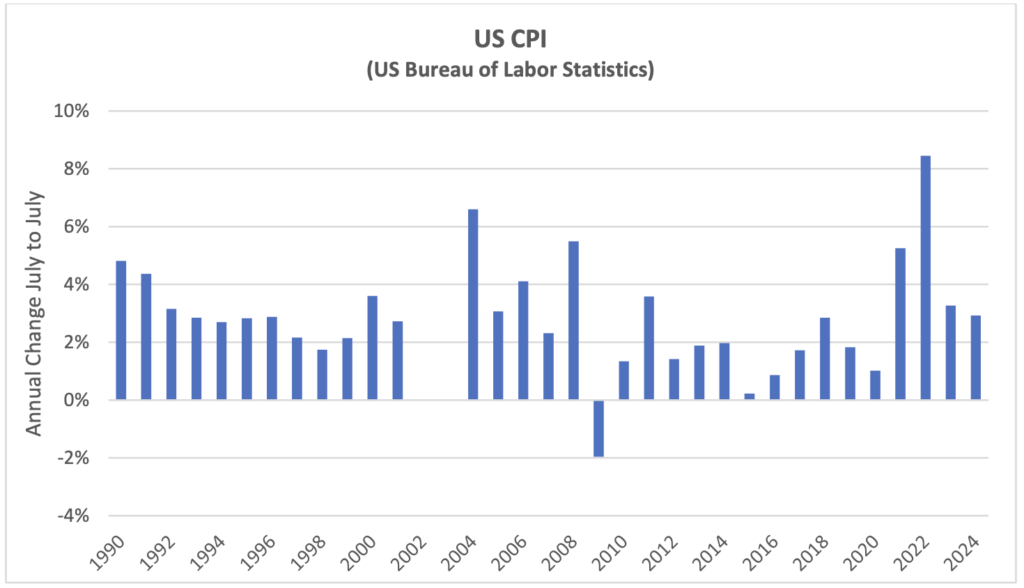

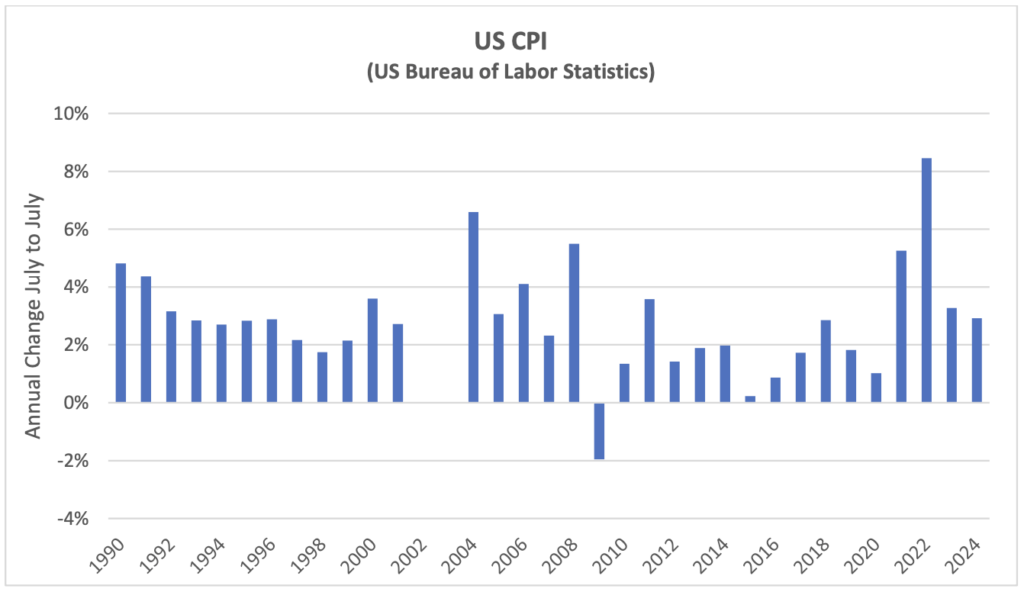

Although medium or long-term inflation expectations have never gone higher than 3.5%, actual inflation experience has been much higher in the last few years. This has led to higher appraised values for new aircraft. If tariffs are applied to aircraft and/or aircraft components tis is likely to increase the cost of new aircraft.

Traffic and Aircraft Demand

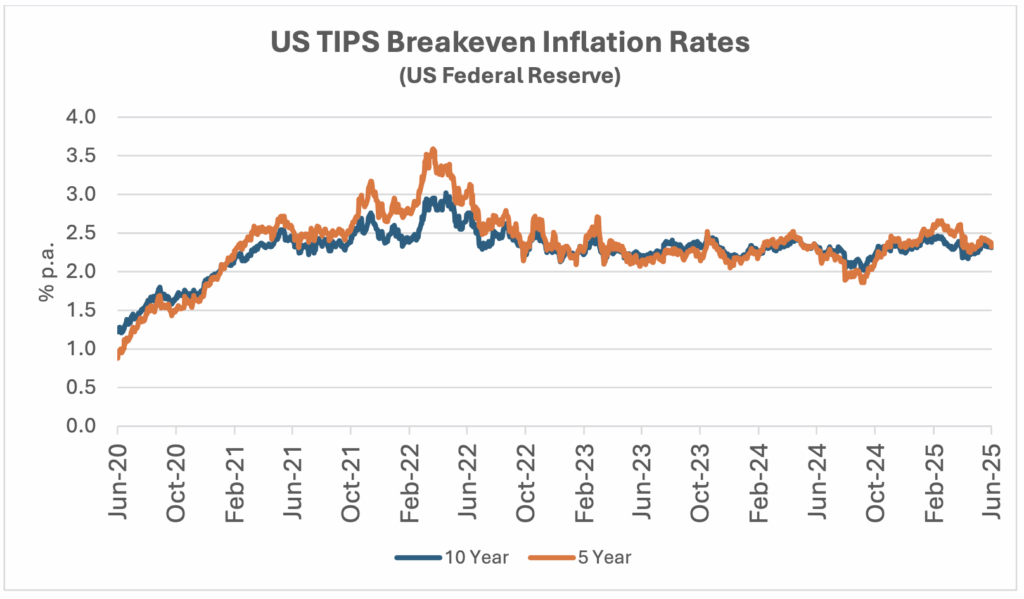

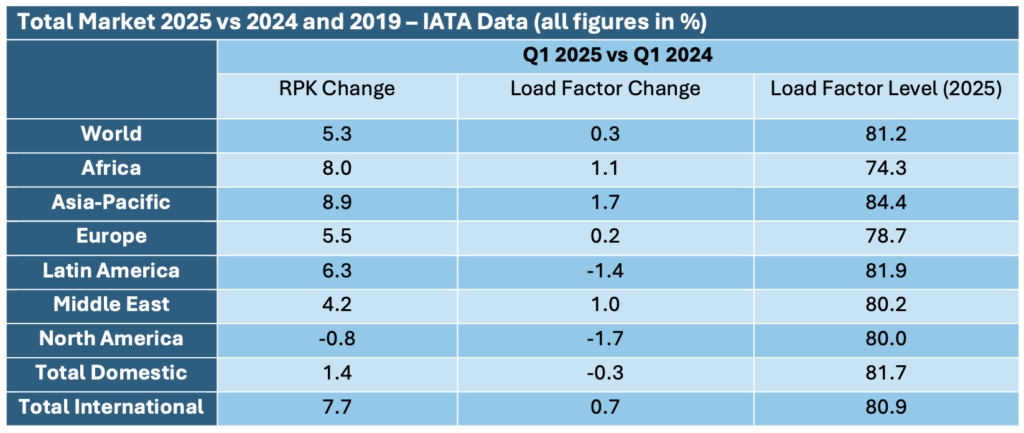

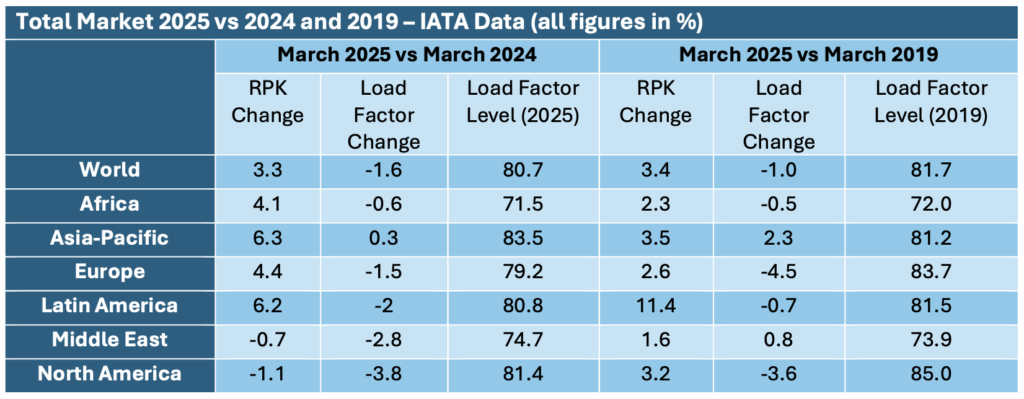

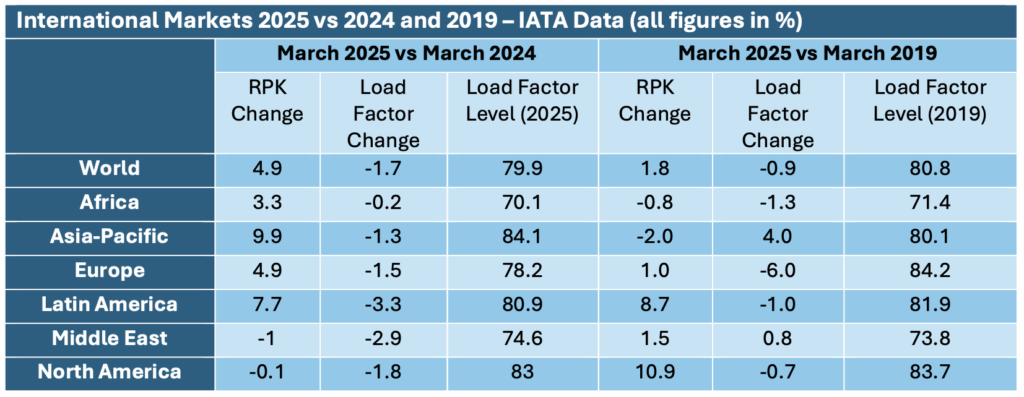

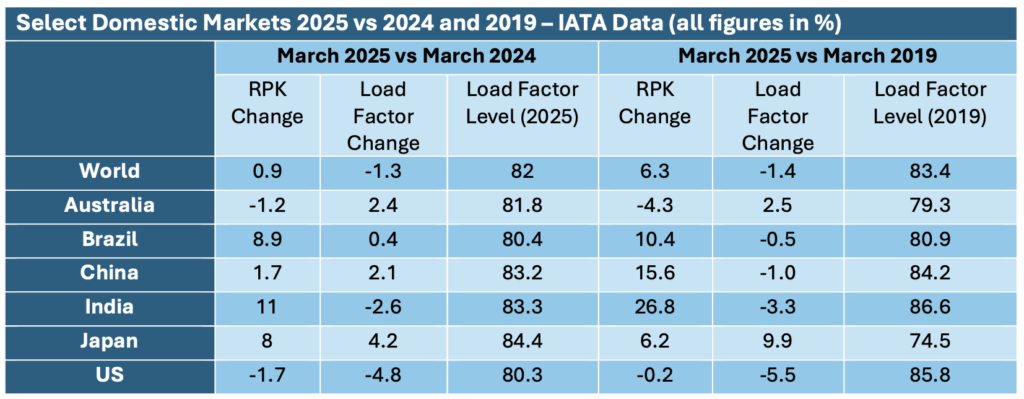

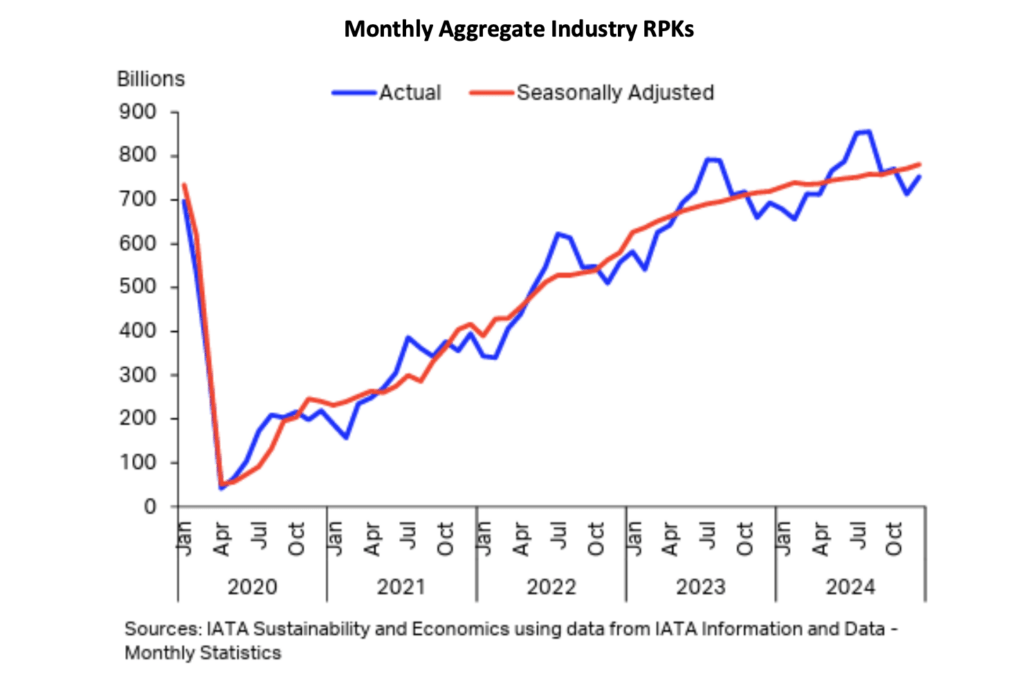

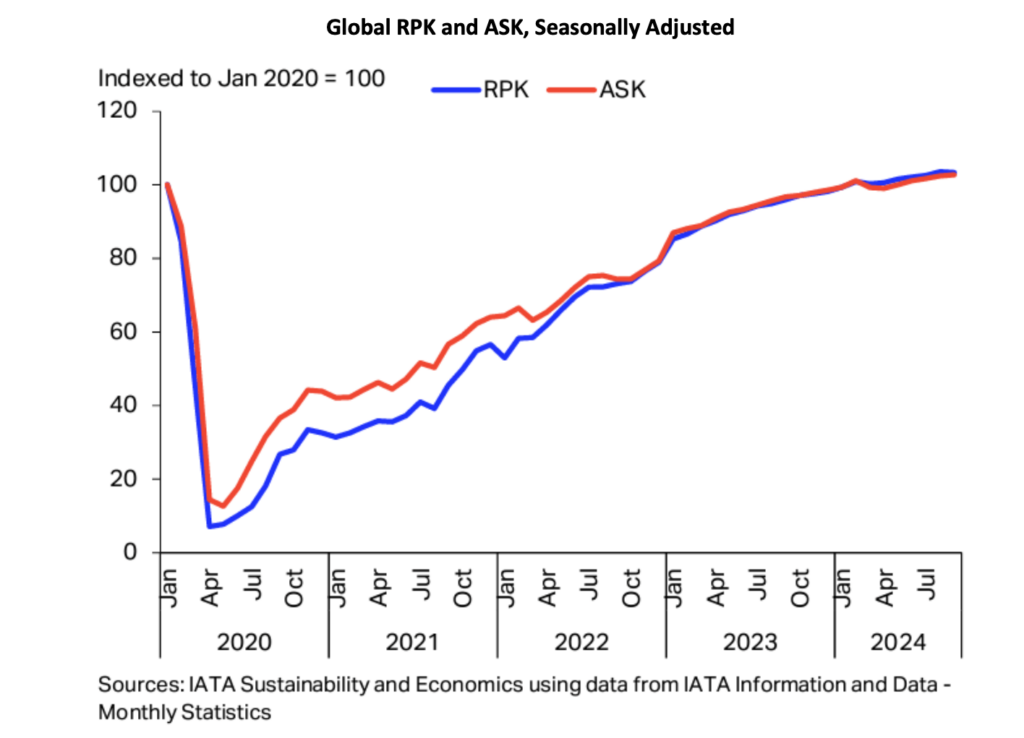

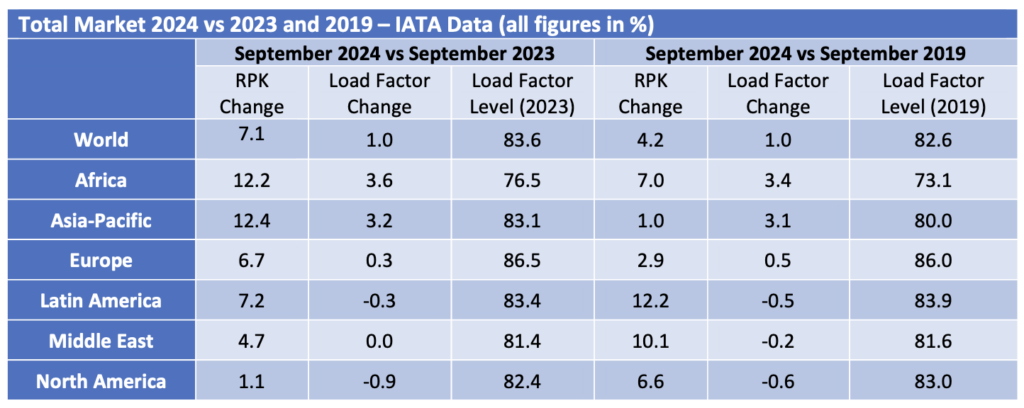

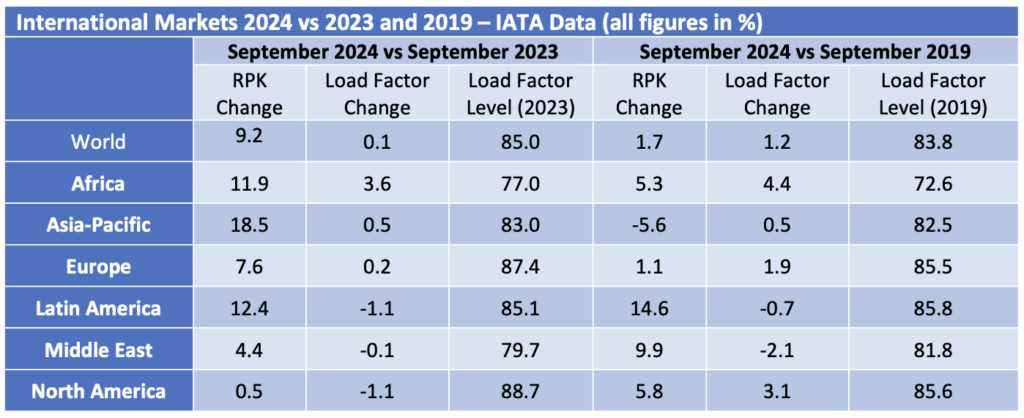

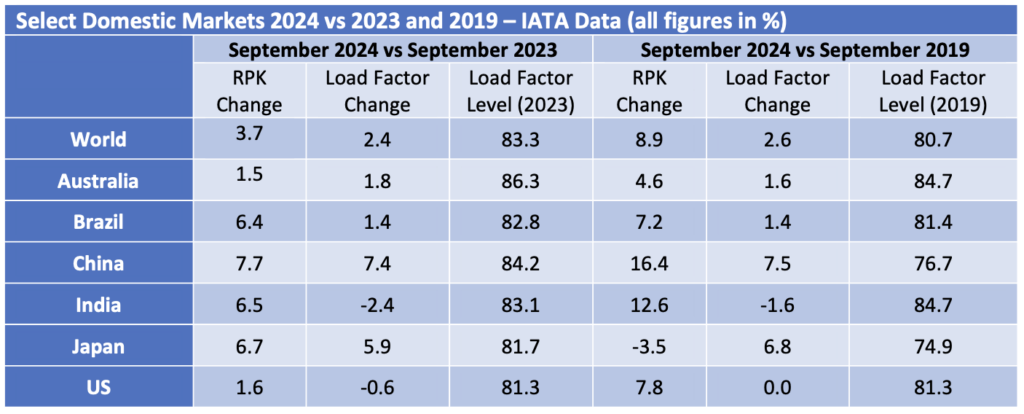

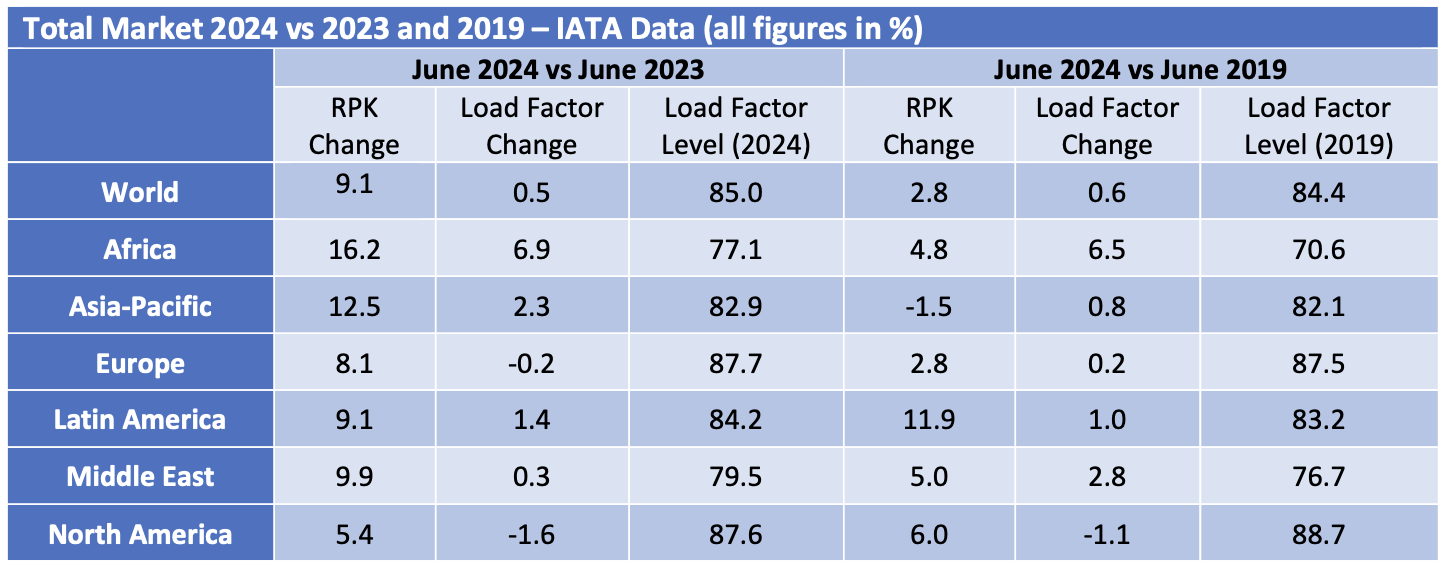

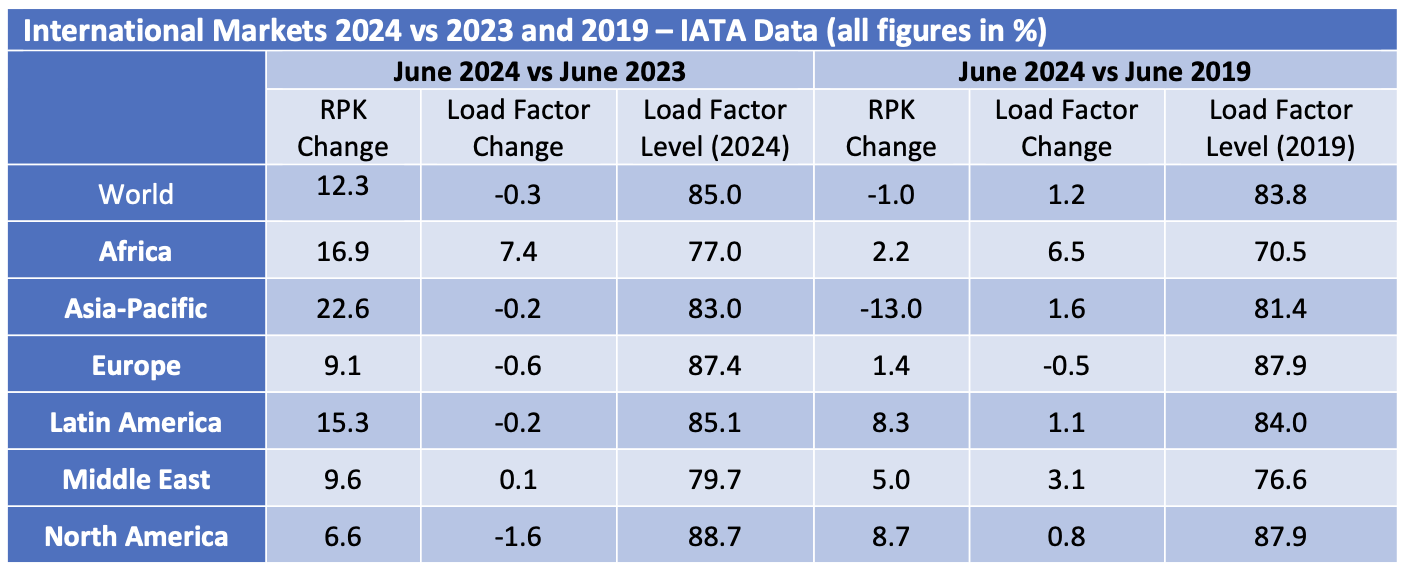

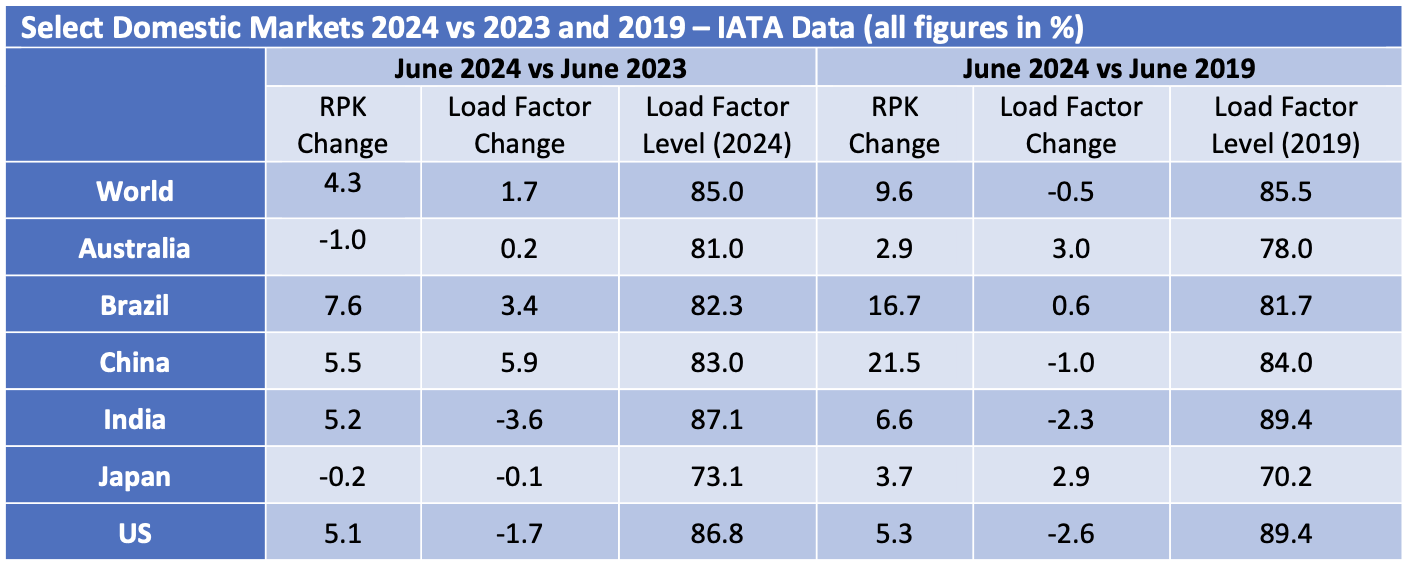

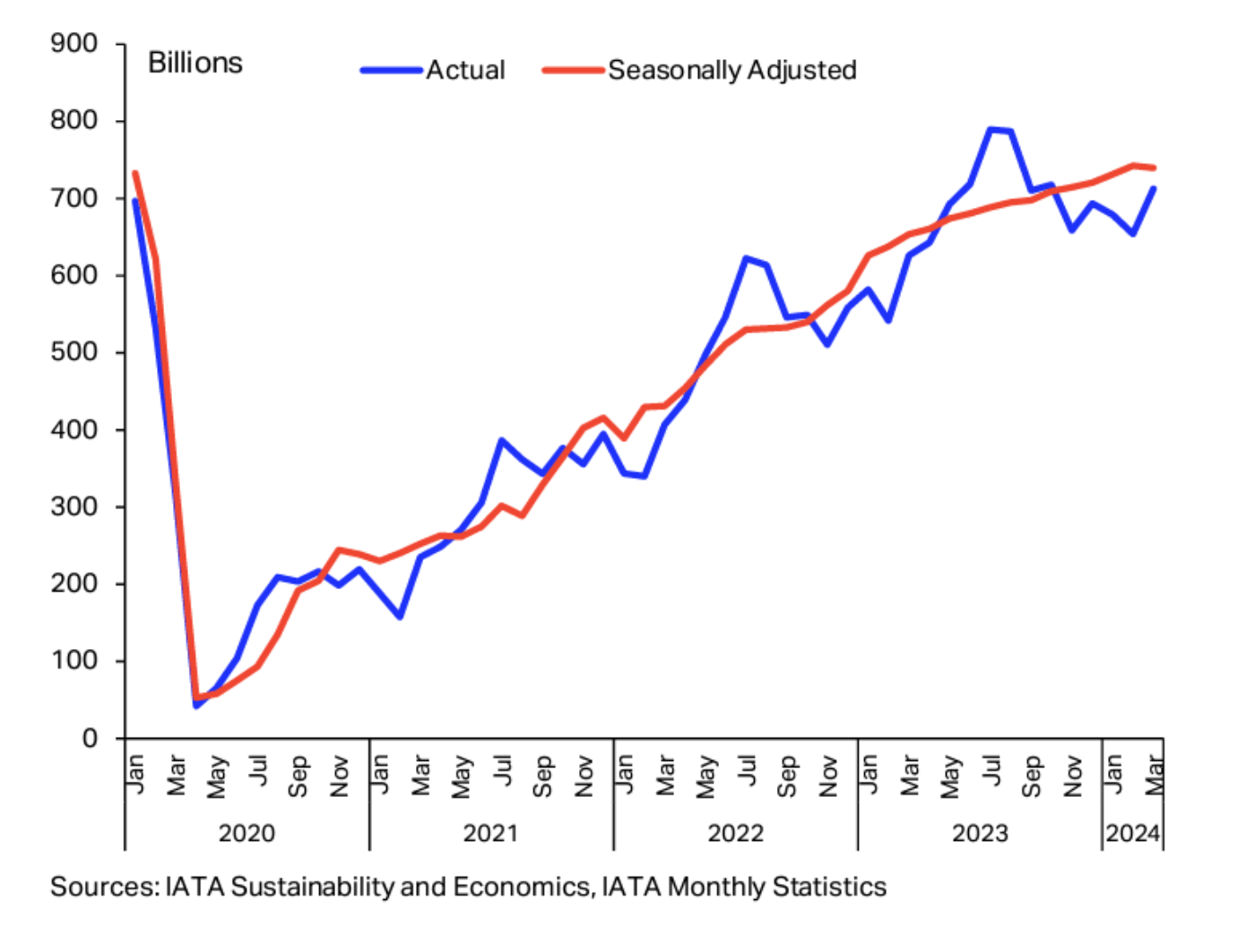

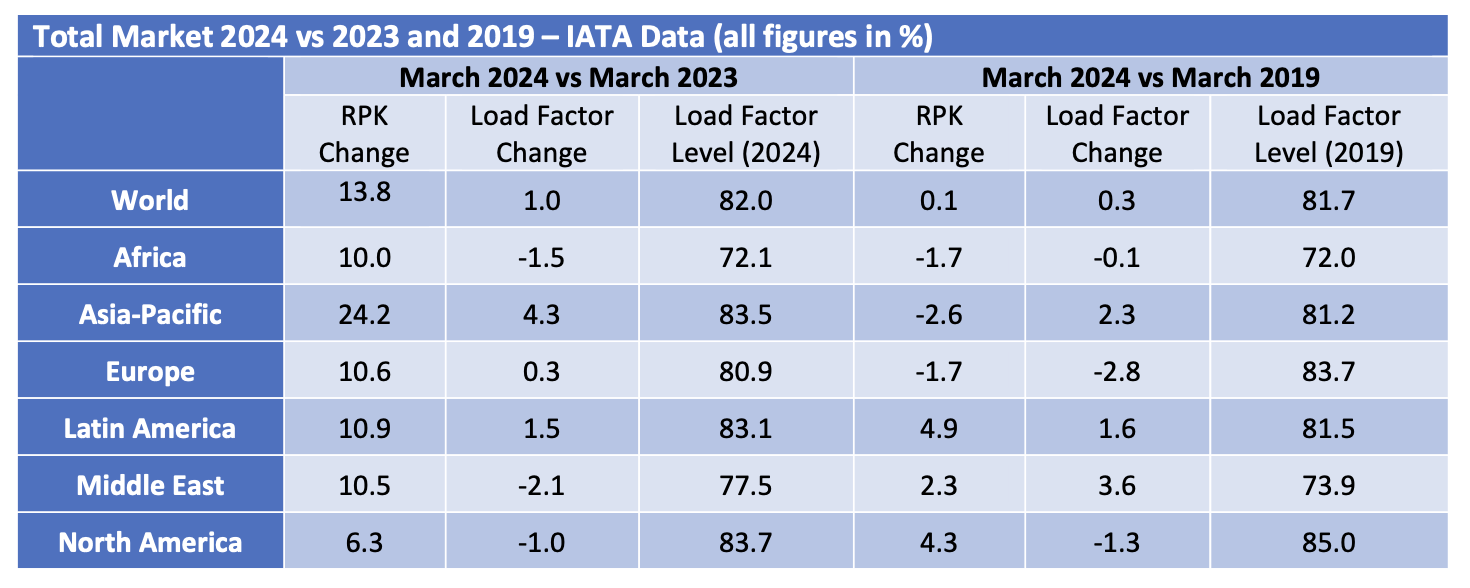

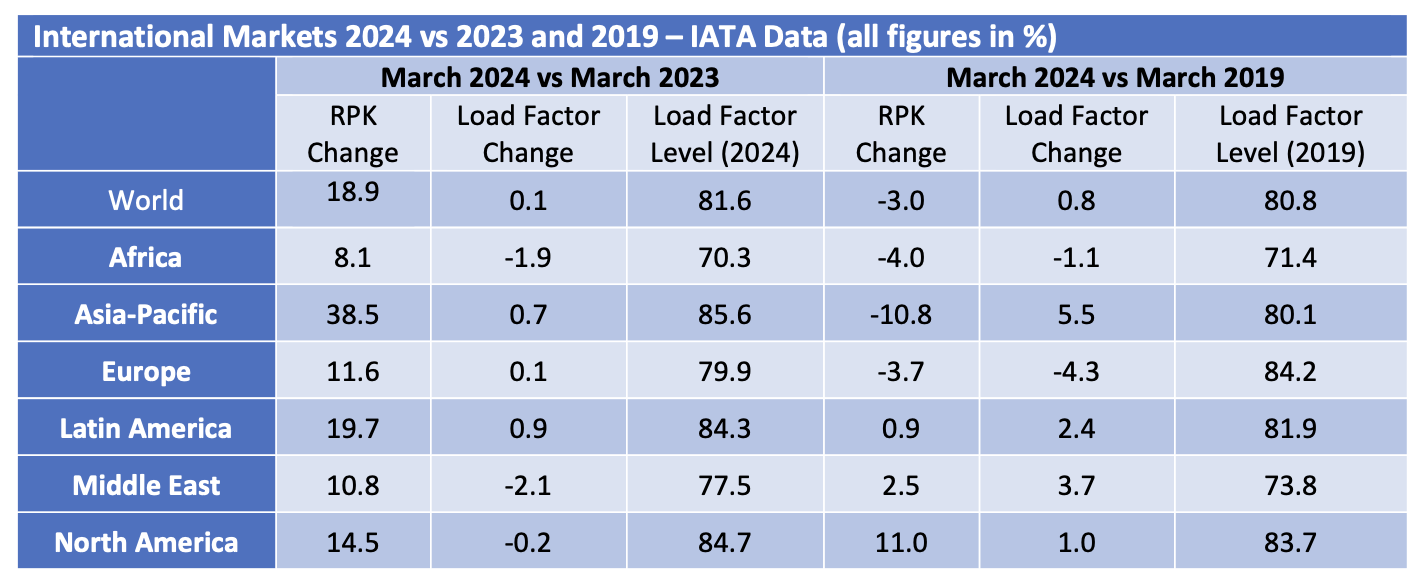

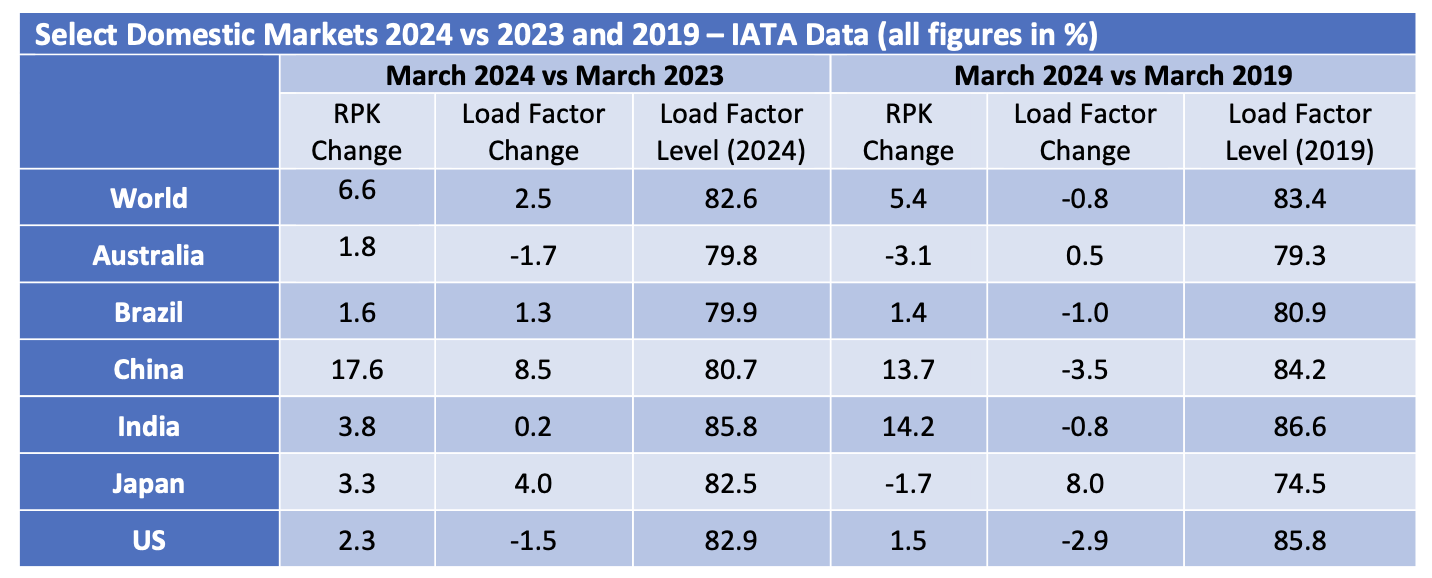

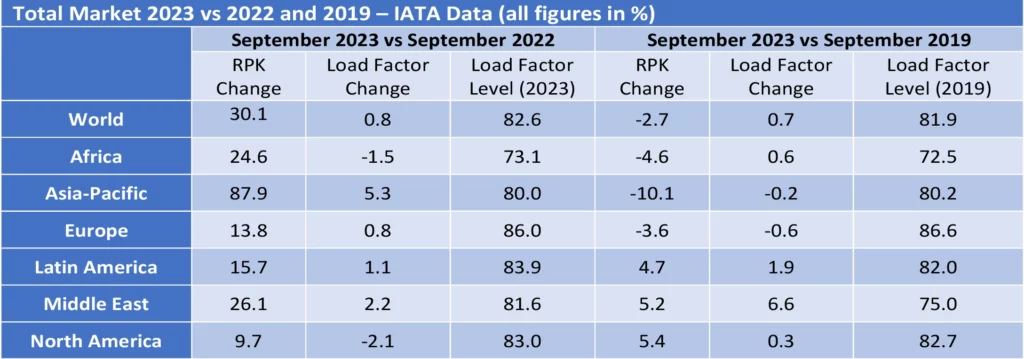

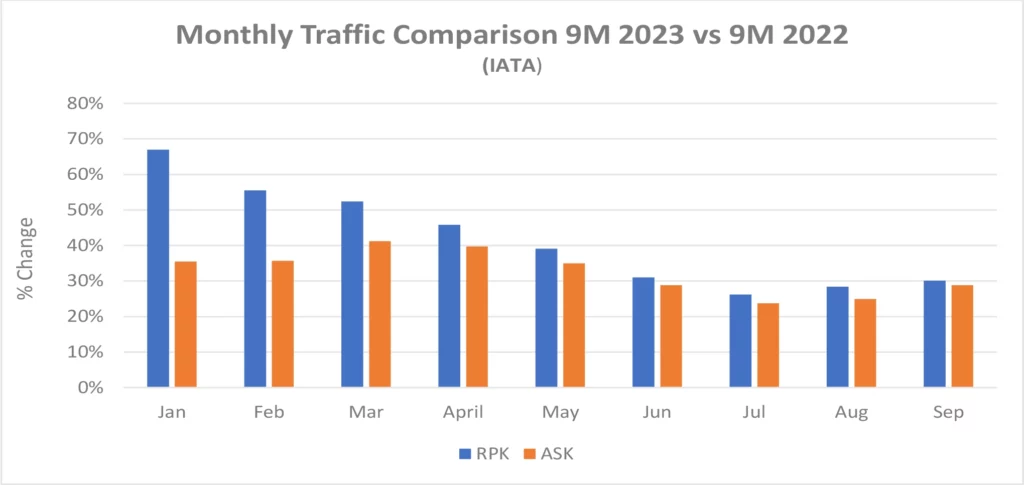

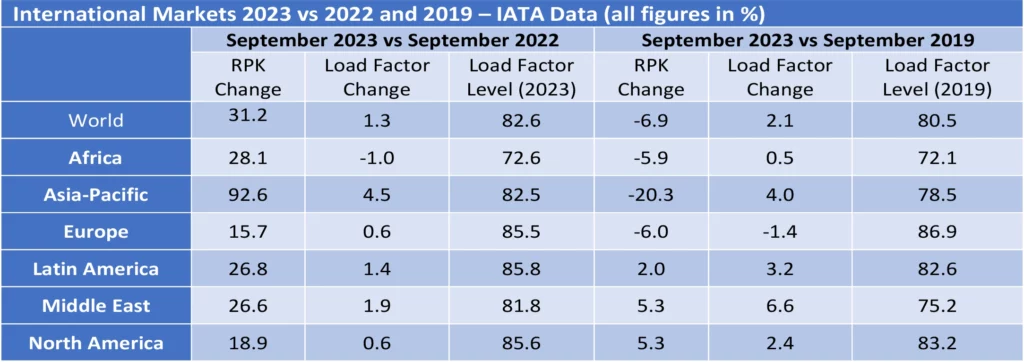

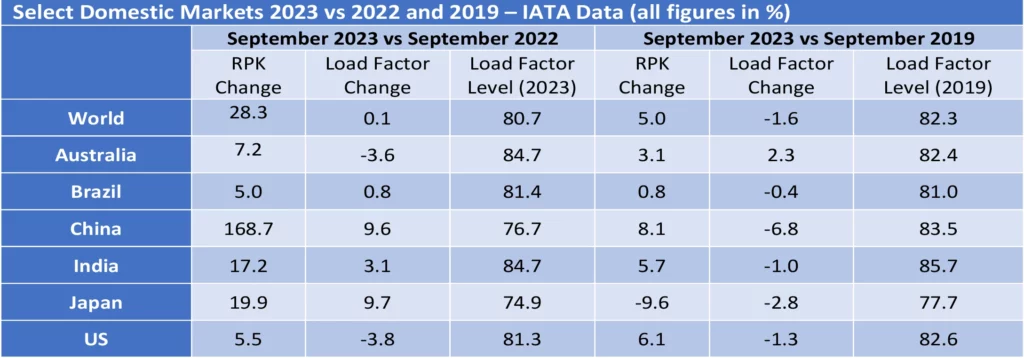

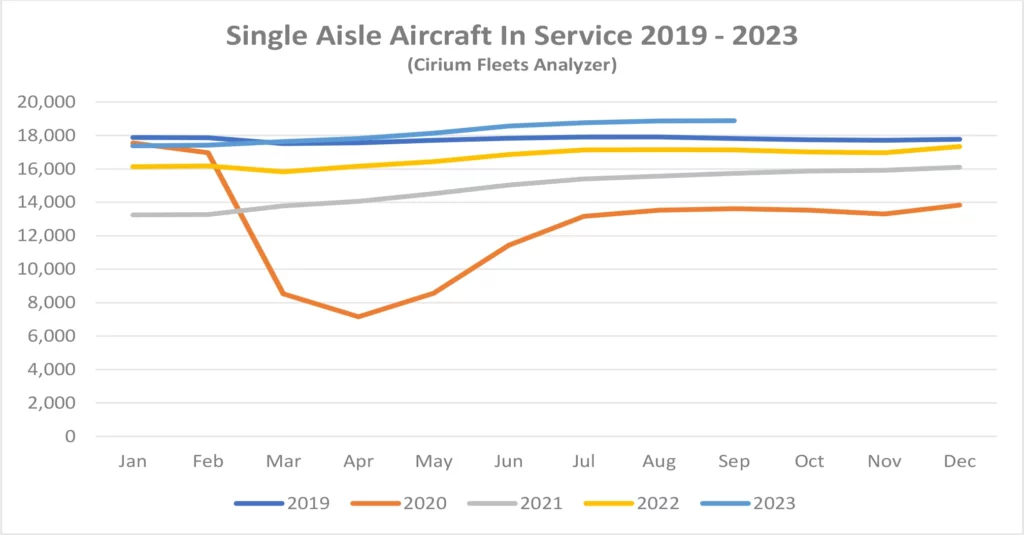

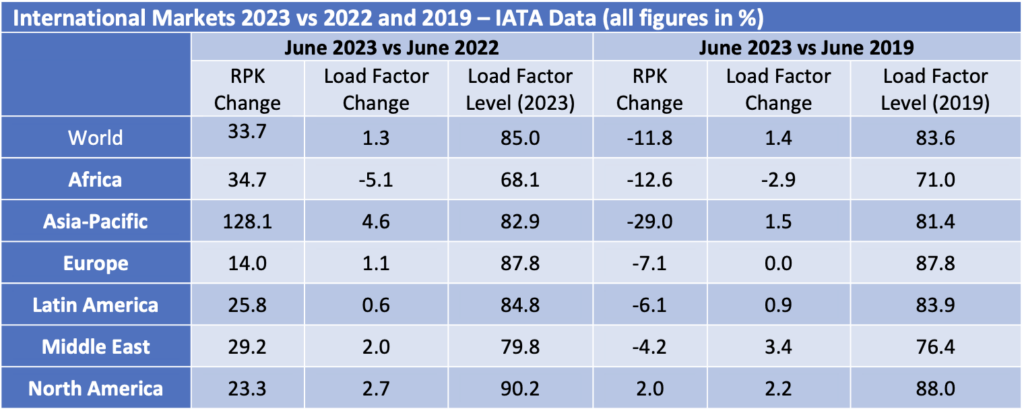

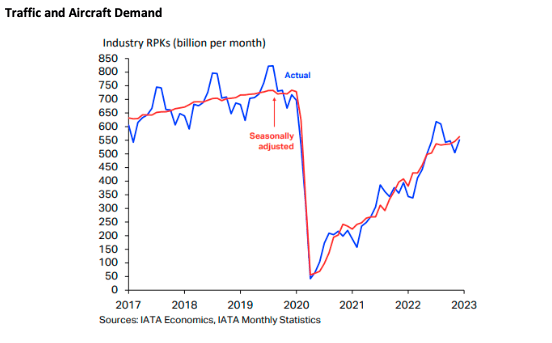

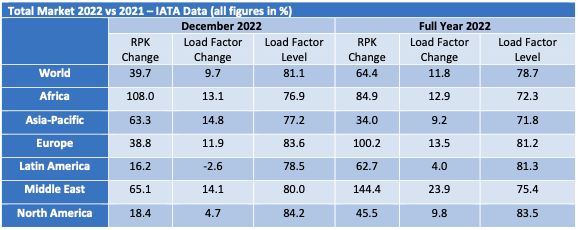

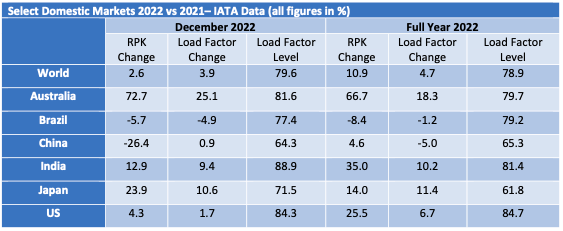

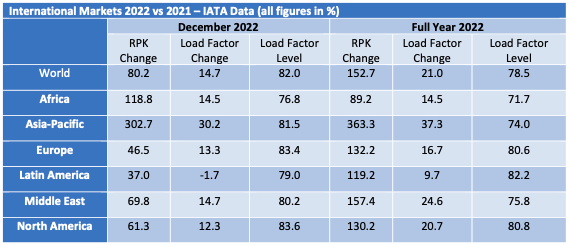

After a very strong January traffic global growth became relatively weaker, although RPKs[2] for the first quarter overall were up 5.3% and a slightly lower increase in ASKs[3] allowed for a modest improvement in load factor. The key growth driver was international traffic in Asia-Pacific which has lagged other markets in its post-pandemic recovery. This was significantly offset by weakness in both domestic and international North American traffic where volatile economic policy in the US appears to have had a negative impact on consumer confidence.

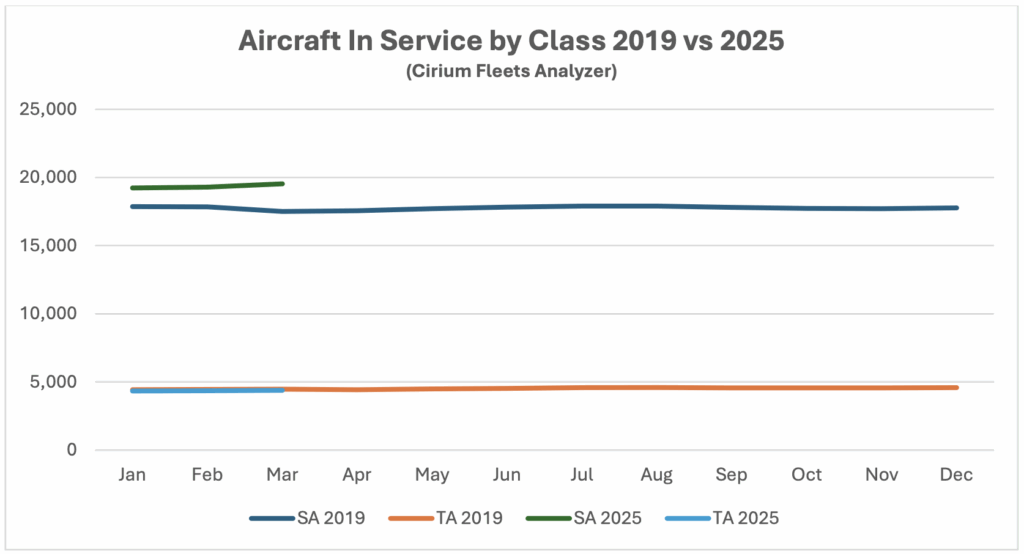

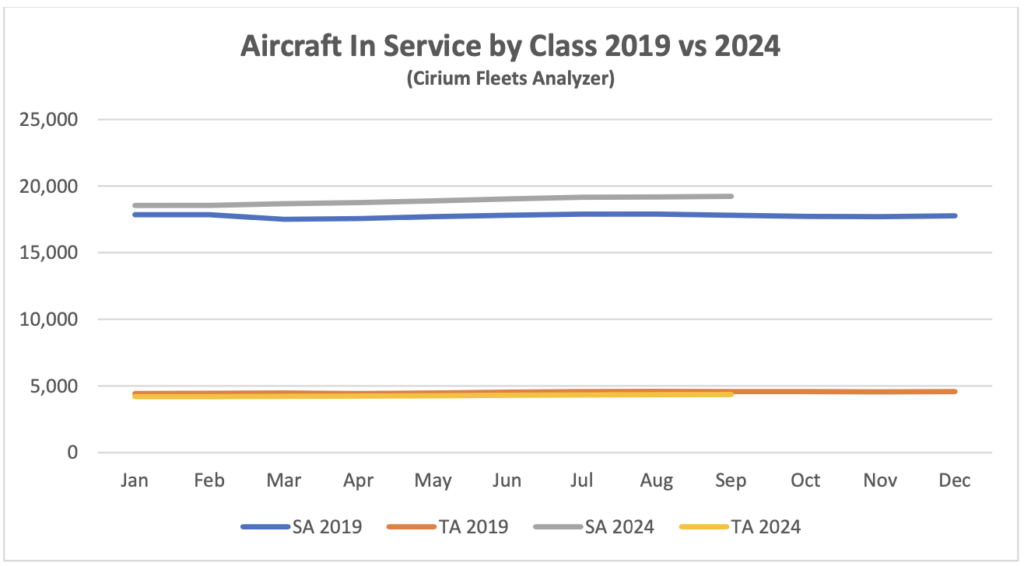

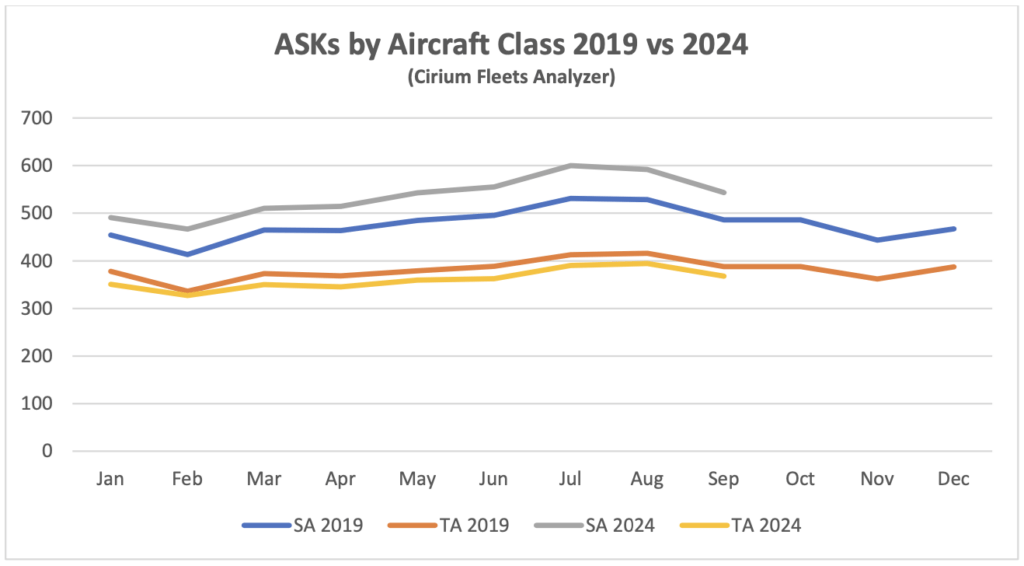

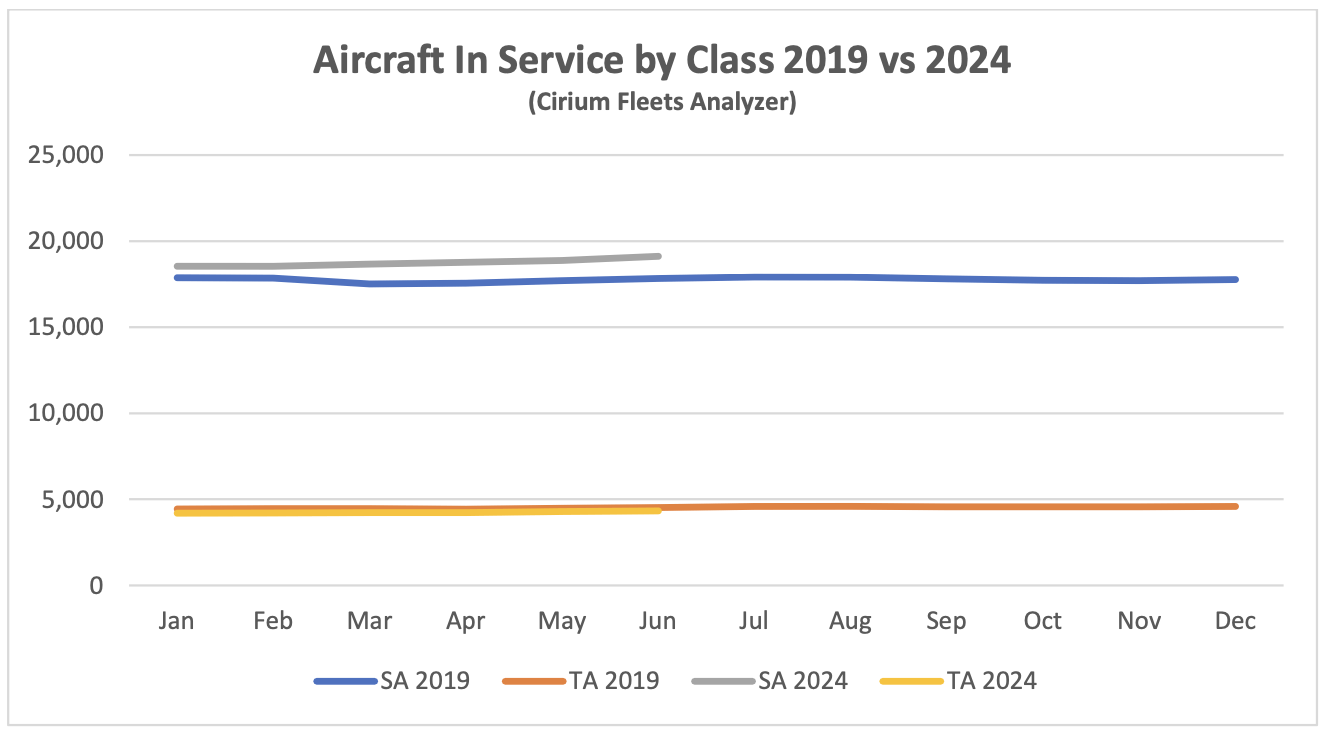

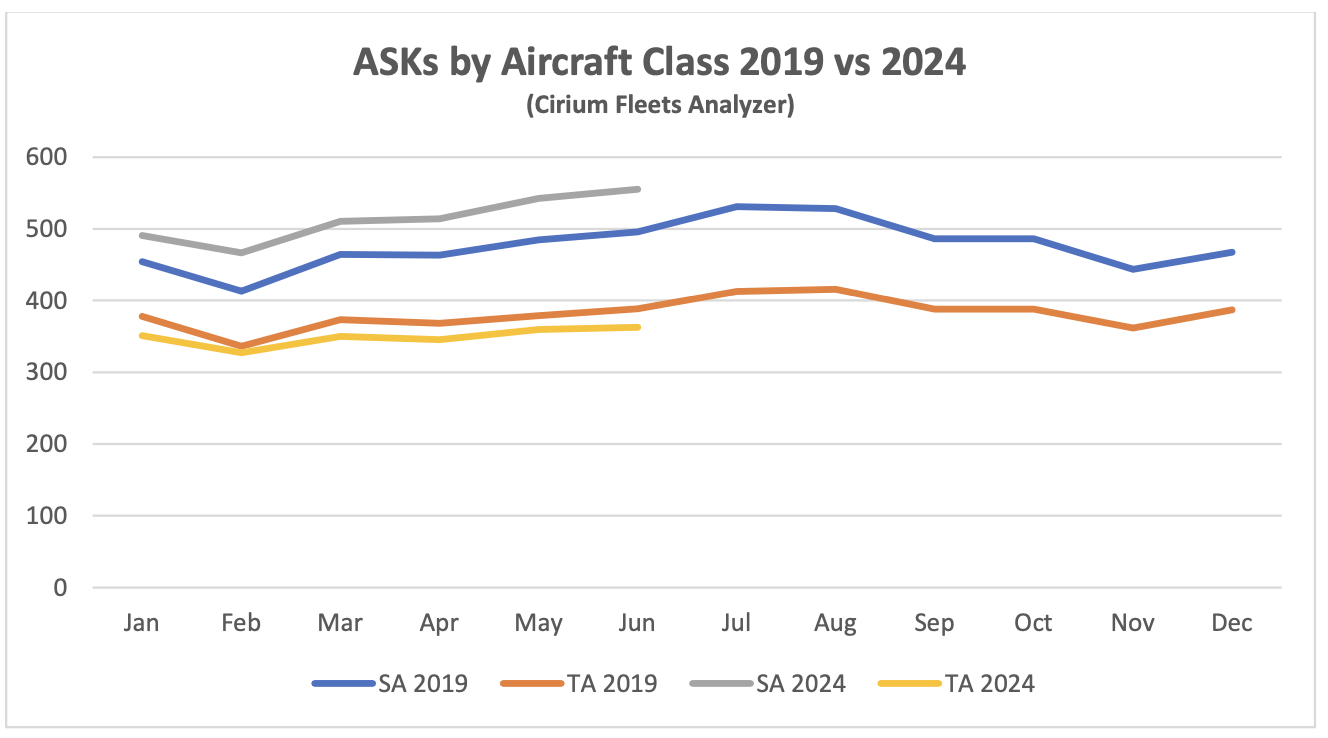

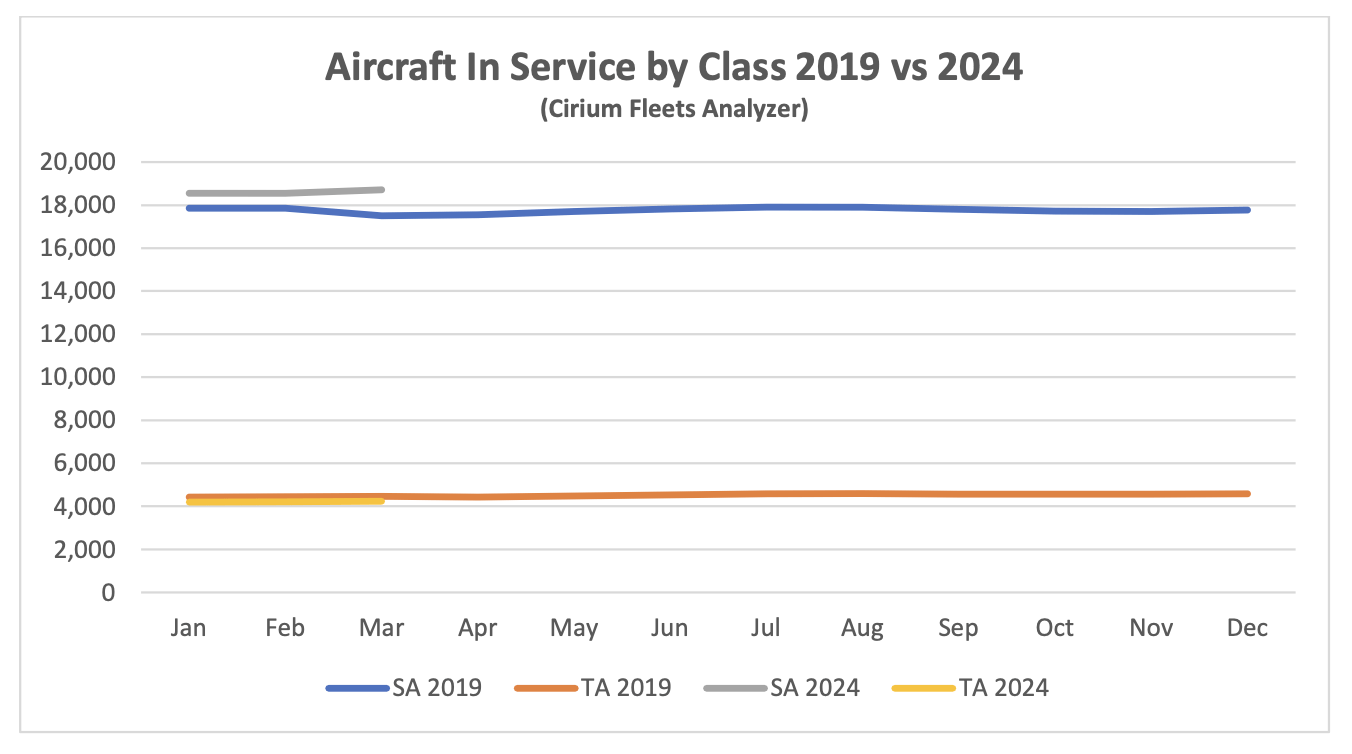

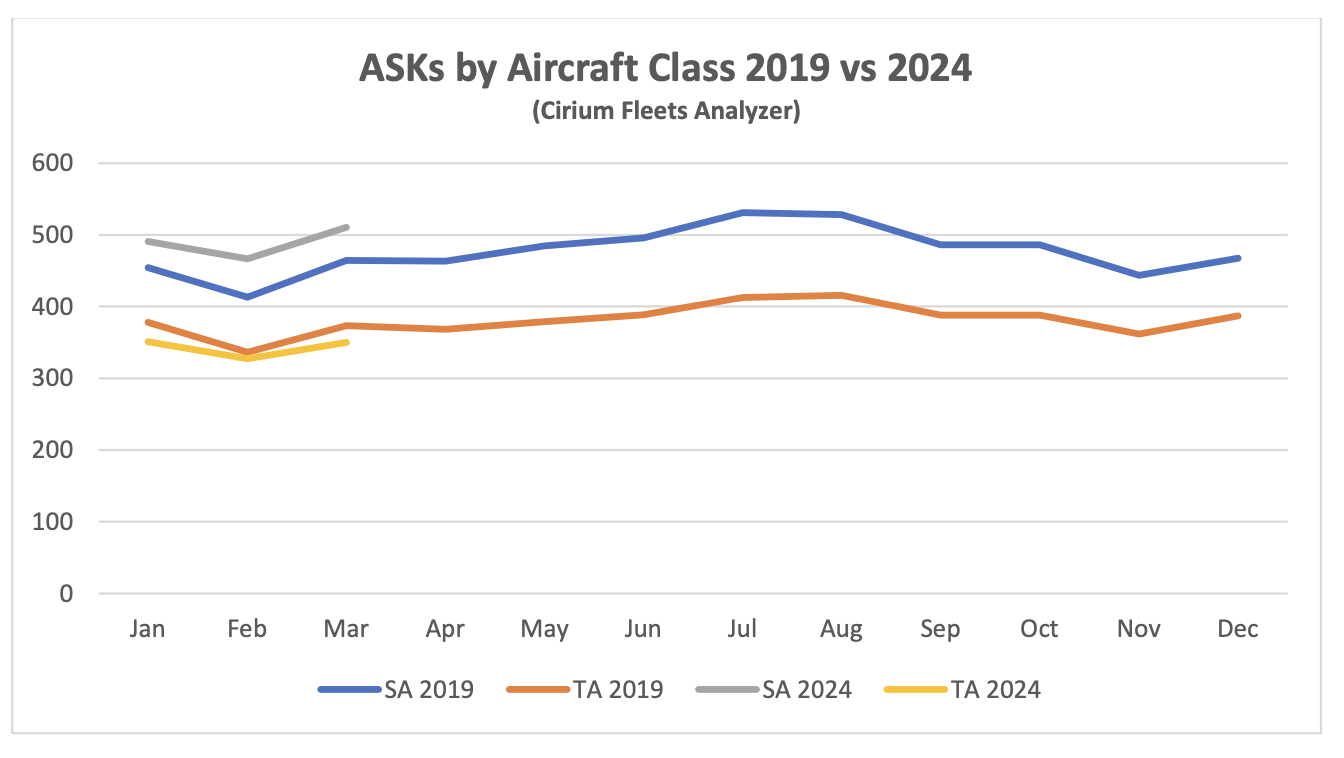

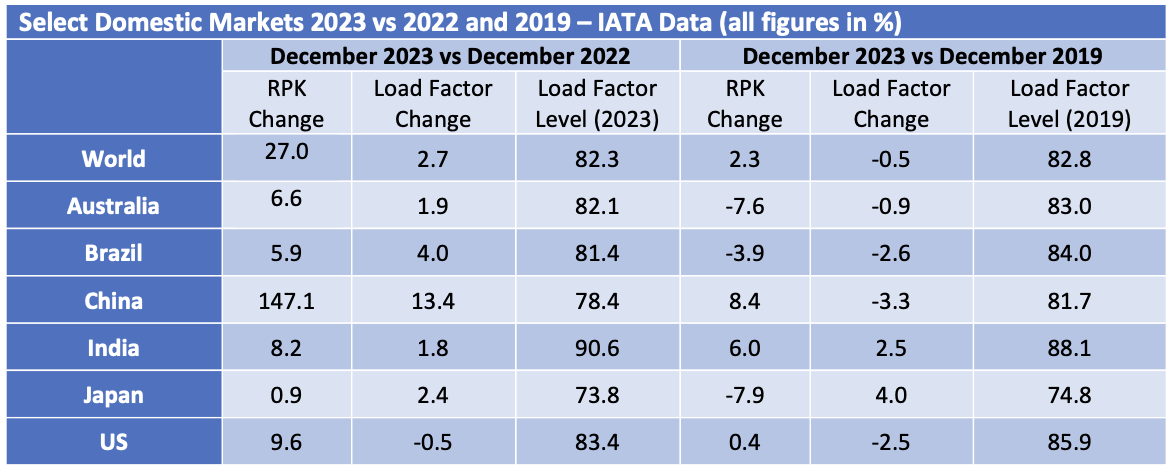

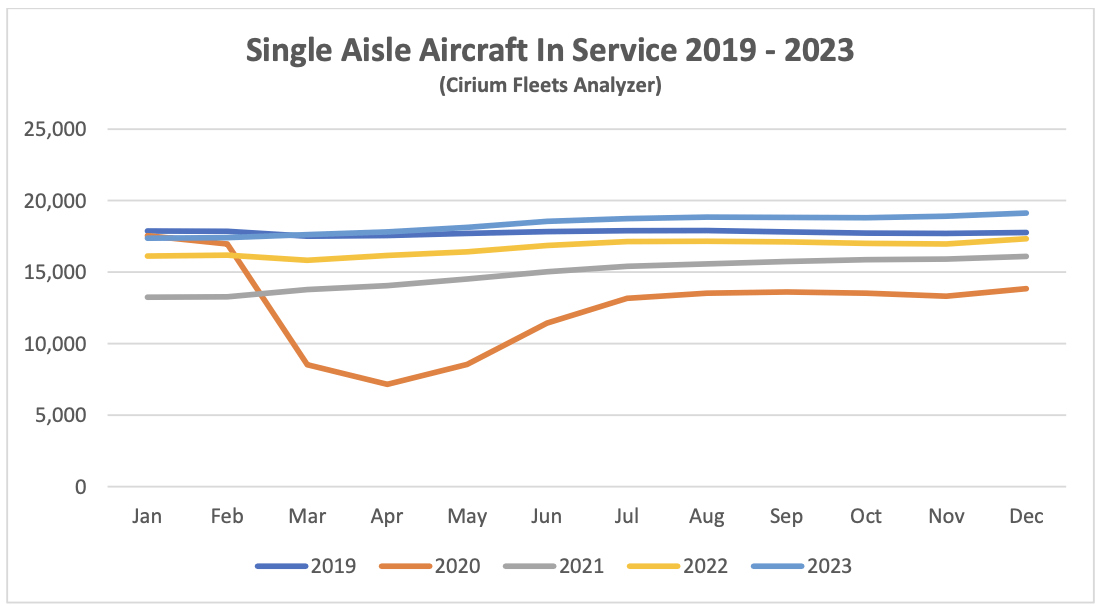

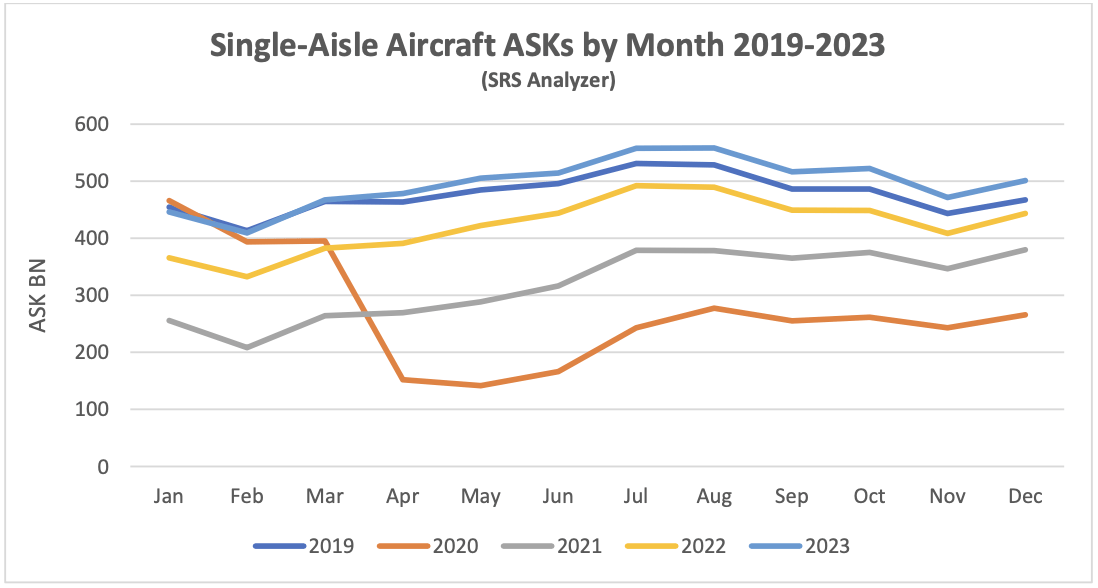

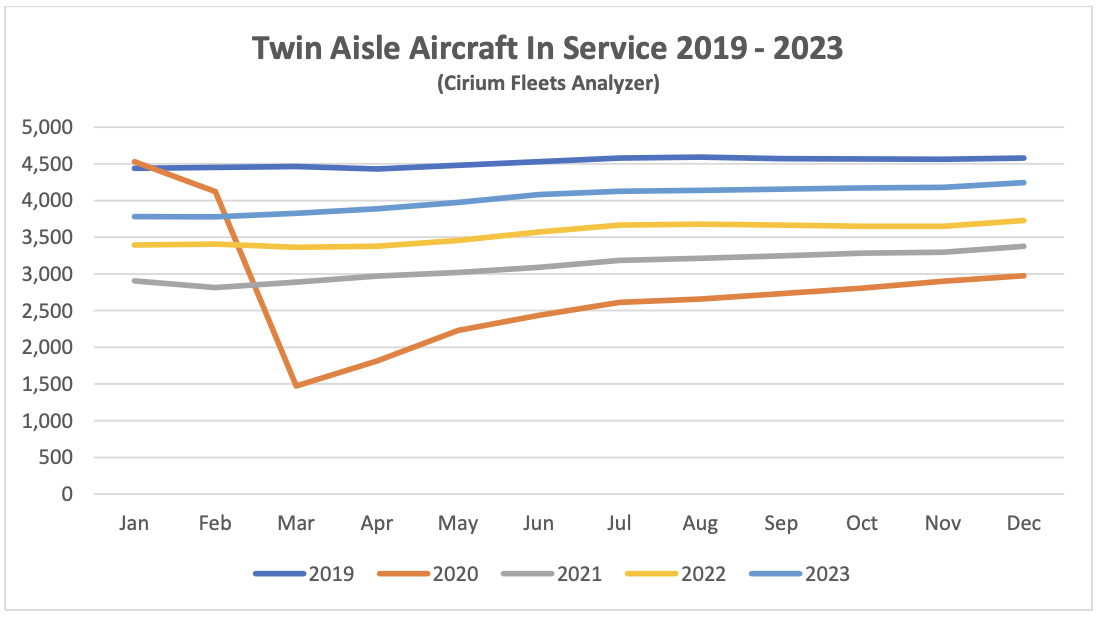

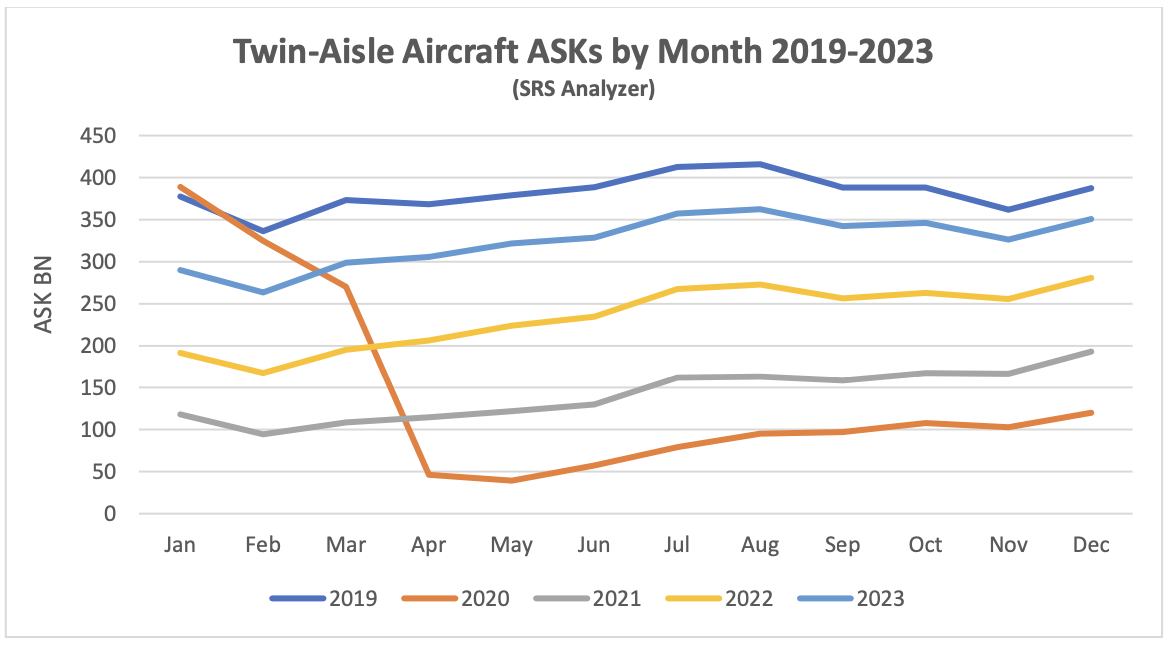

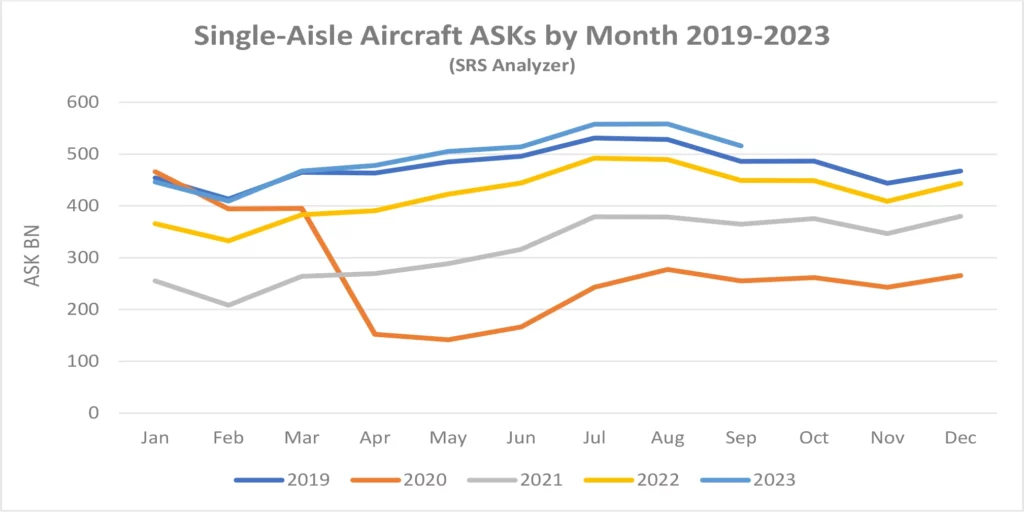

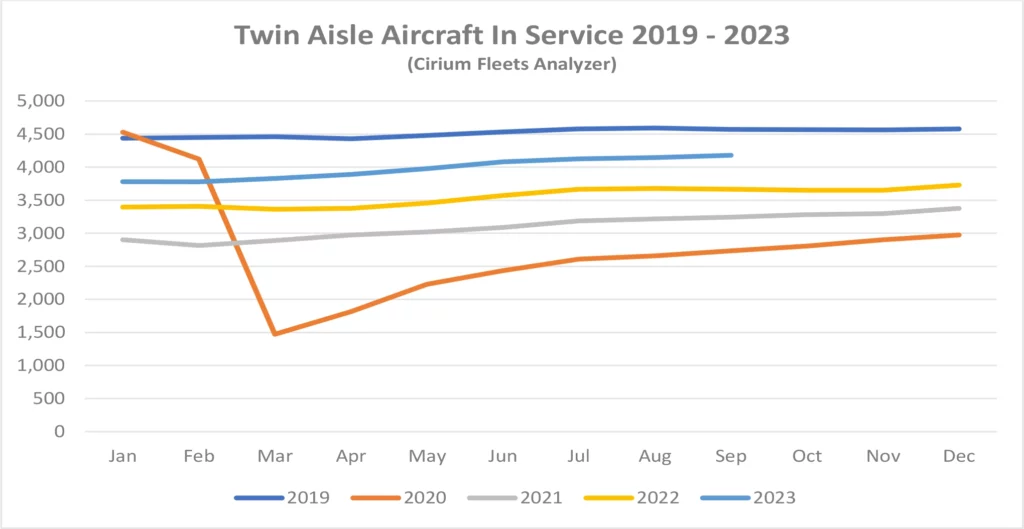

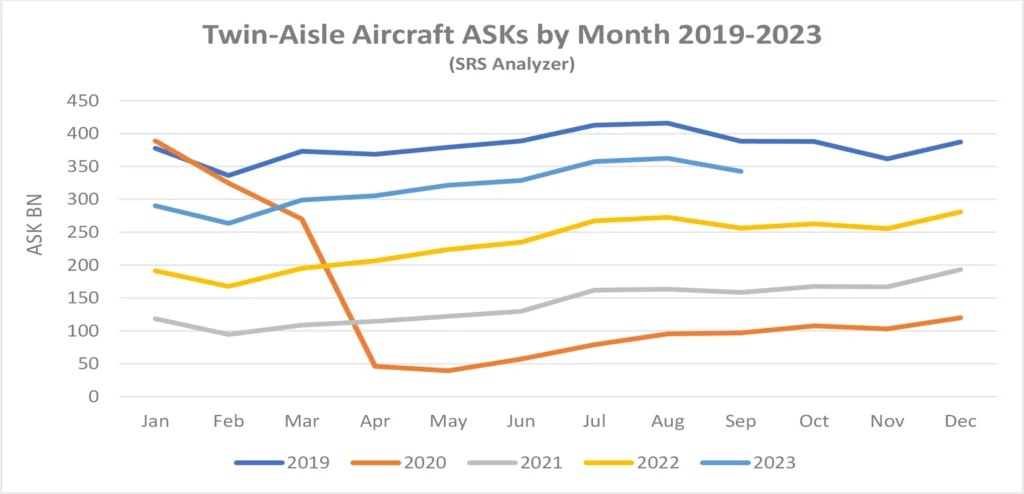

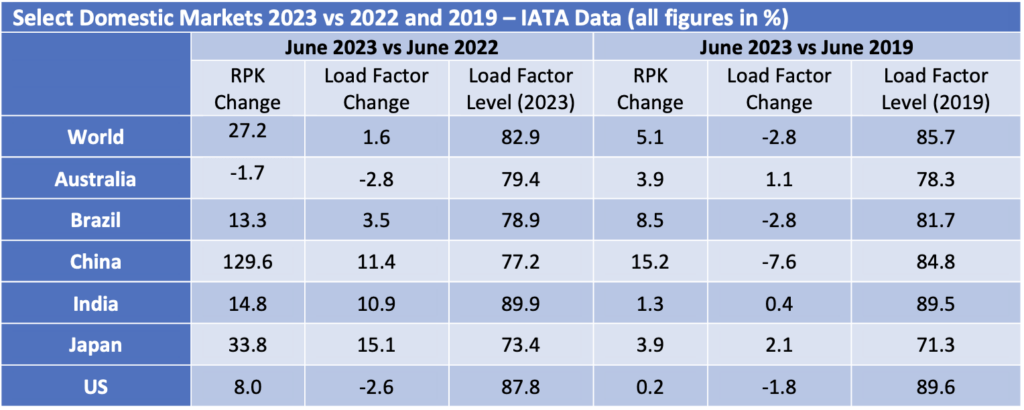

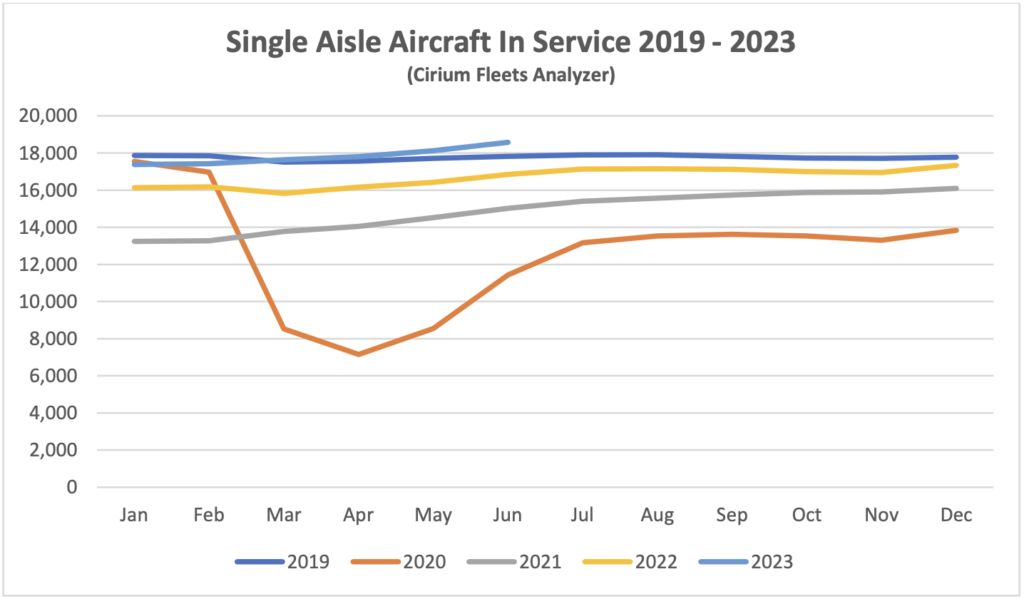

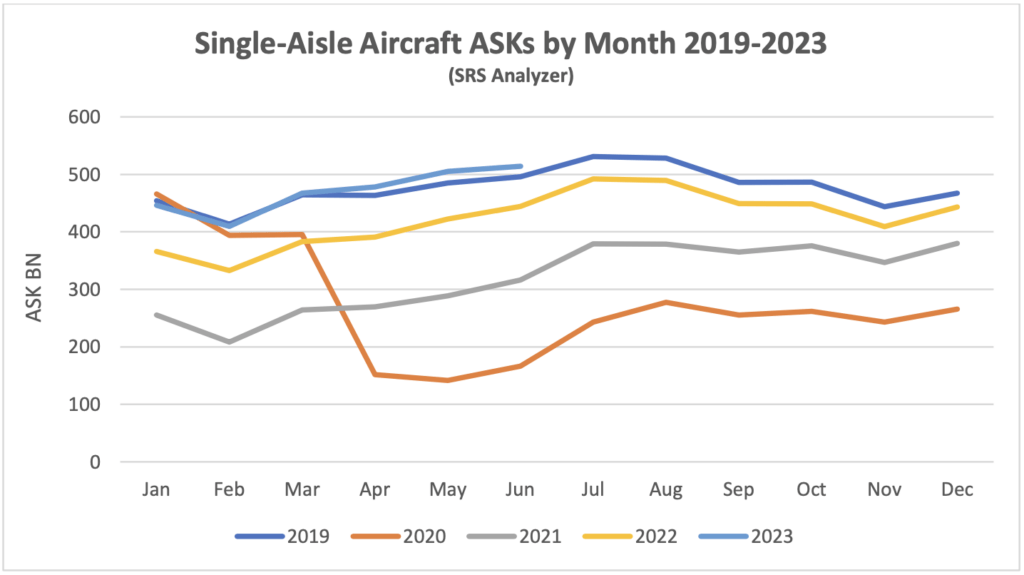

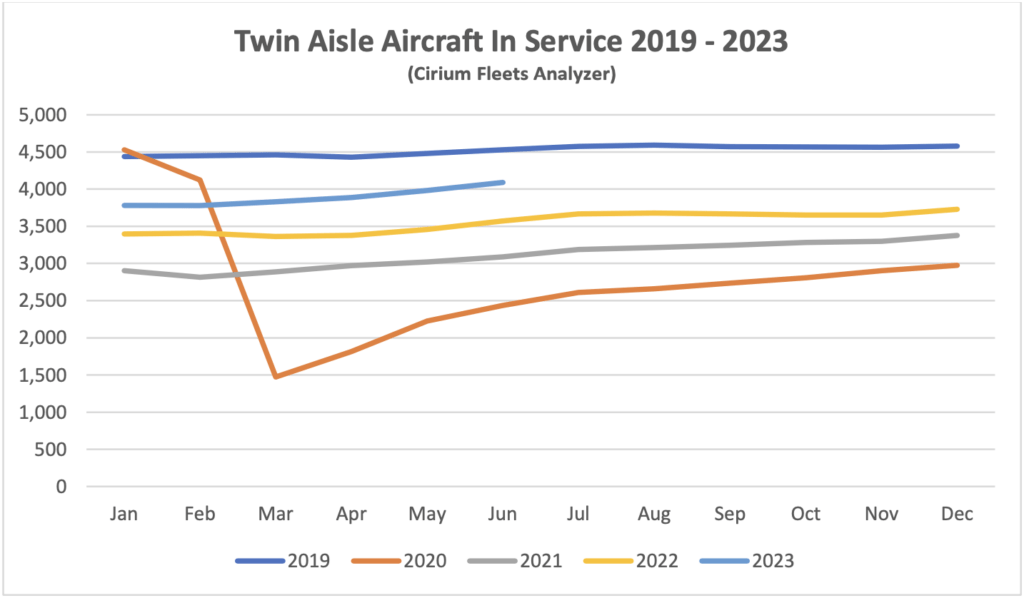

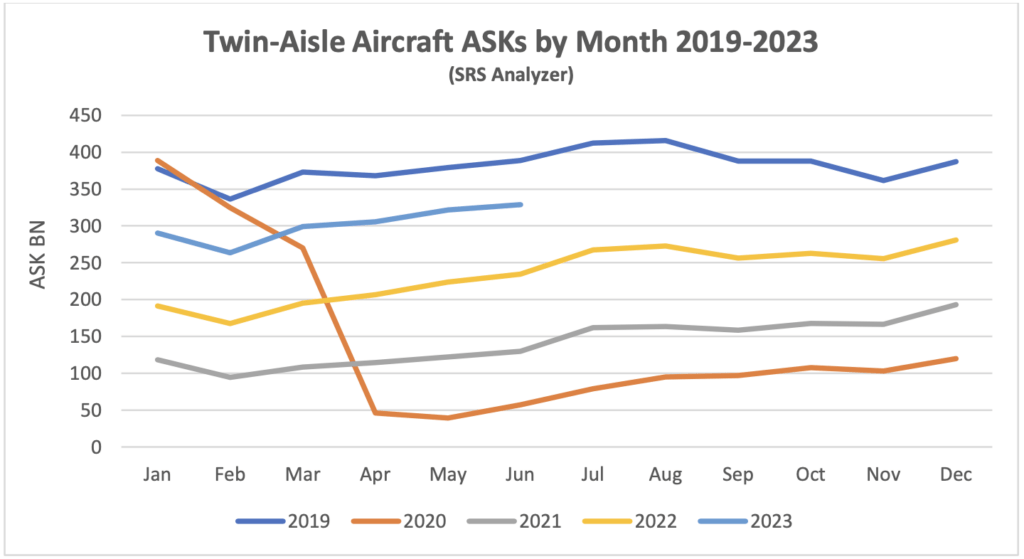

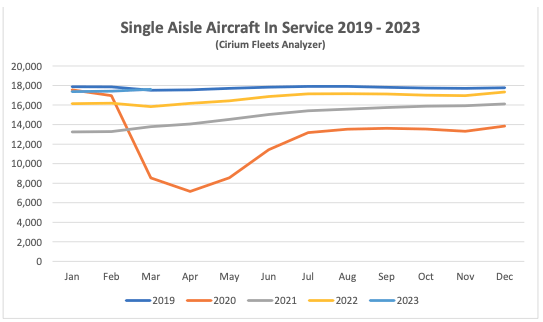

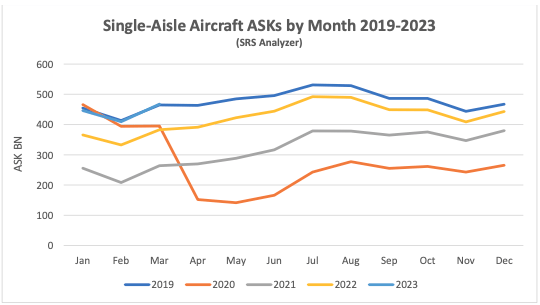

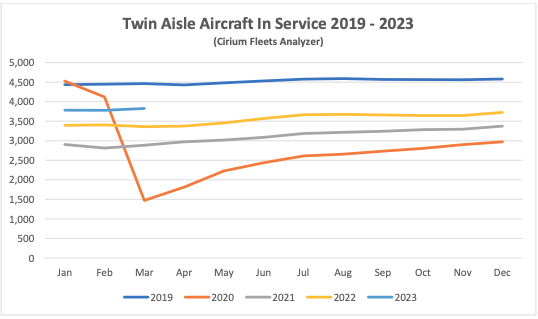

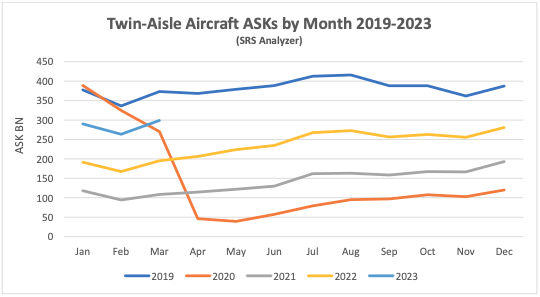

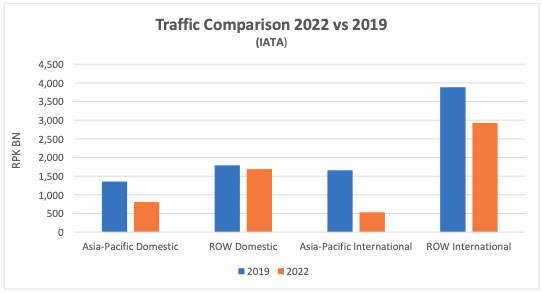

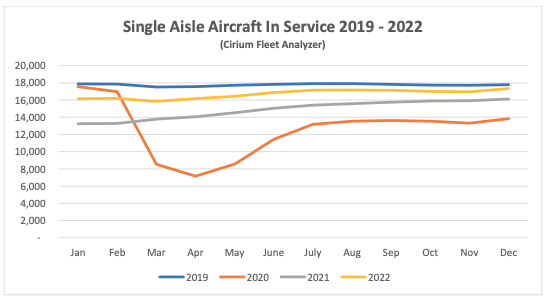

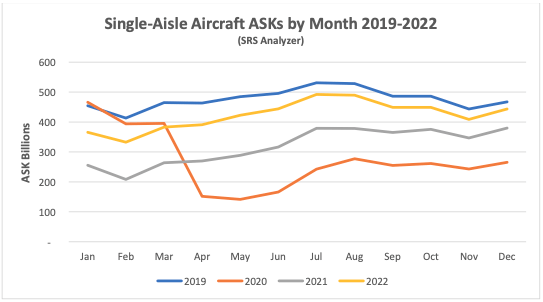

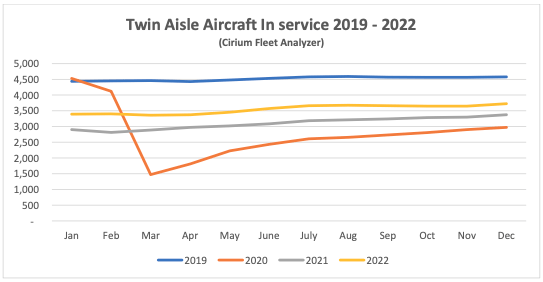

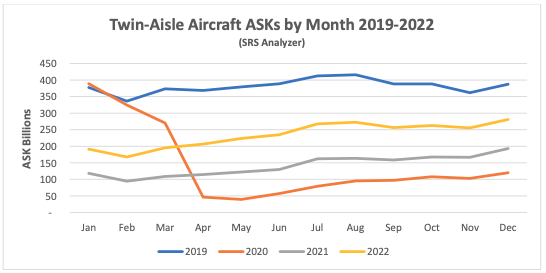

Although some short-haul aircraft serve international routes nearly all long-haul aircraft do so, and this is reflected in the relative demand for single-aisle (narrowbody) and twin-aisle (widebody) aircraft. Aircraft demand can be measured in terms of aircraft in service and ASKs, the standard measure of aircraft capacity deployed by airlines which indicates how intensively aircraft are being flown. Single aisle aircraft demand on both metrics is higher so far in 2025 than in 2019 whereas twin-aisle aircraft are in line.

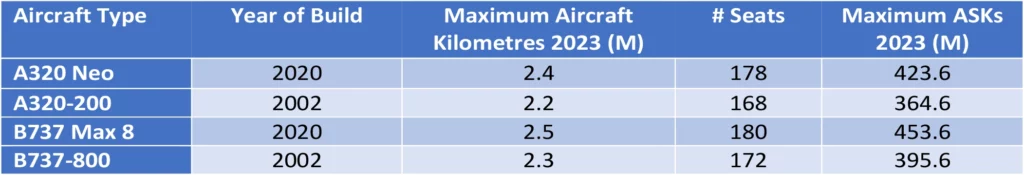

The softer recovery for twin-aisle aircraft is mainly due to weak traffic to and from, and within the Asia-Pacific region. The figures by region in the tables above are based on airline domicile, so weak Europe to Asia traffic reduces recorded international RPKs in other regions. This short-term effect is accompanied by a very gradual long-term increase in single-aisle aircrafts’ share of global airline capacity at the expense of twin-aisle aircraft, which is caused by better operator economics and an increase in the number of markets where single-aisle aircraft can be deployed because of the greater range of new technology aircraft such as the A320 Neo and the B737 Max.

Full recovery has yet to be achieved for twin-aisle aircraft, mainly due to weak traffic to and from, and within the Asia-Pacific region. The figures by region in the tables above are based on airline domicile, so weak Europe to Asia traffic reduces recorded international RPKs in other regions. Twin-aisle aircraft in service has shown a greater improvement relative to 2019 than ASKs which suggests that aircraft are being returned to service with lower utilisation in anticipation of continued recovery.

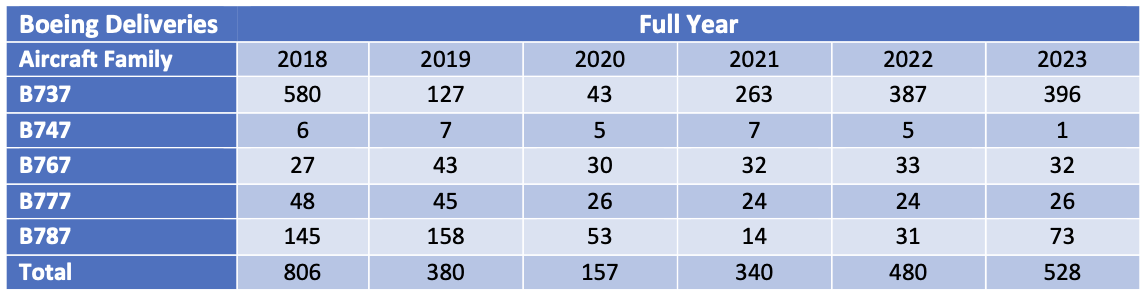

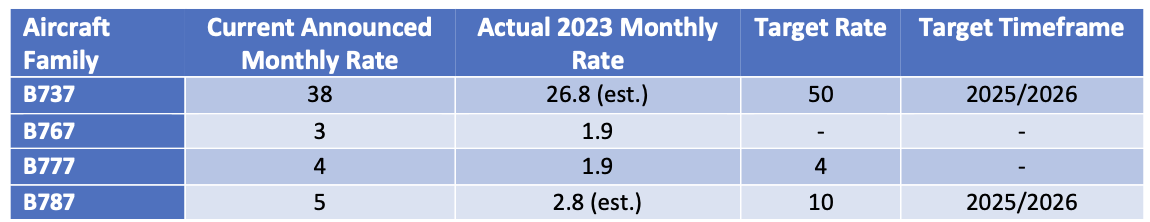

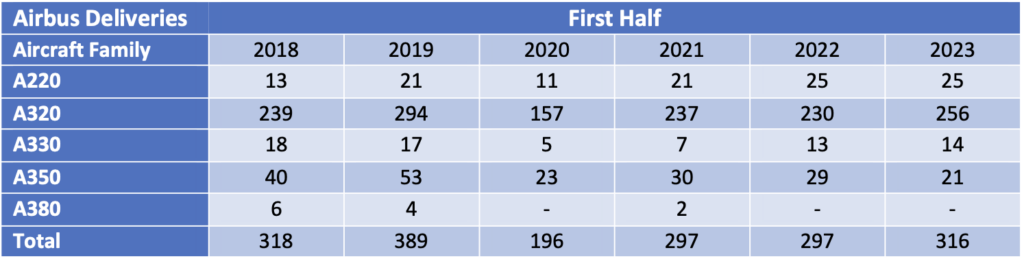

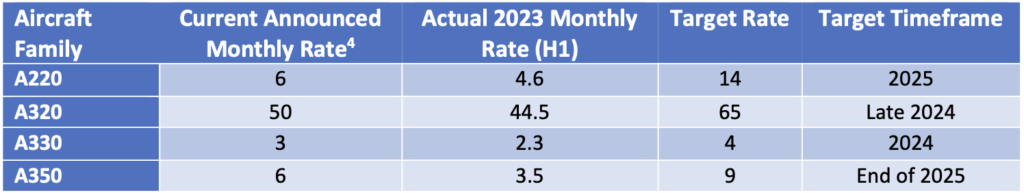

New Aircraft Supply

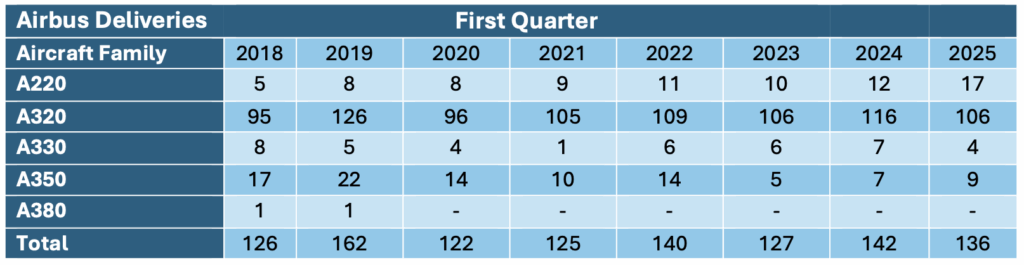

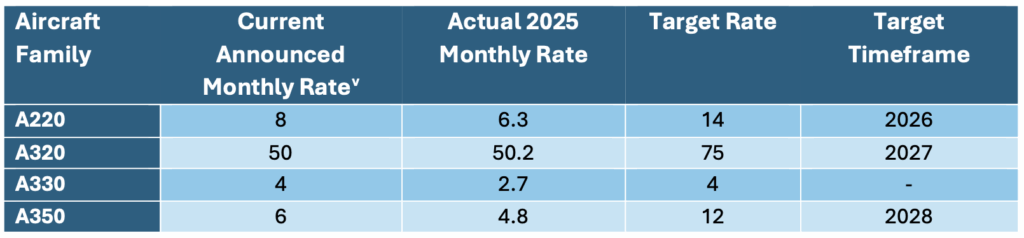

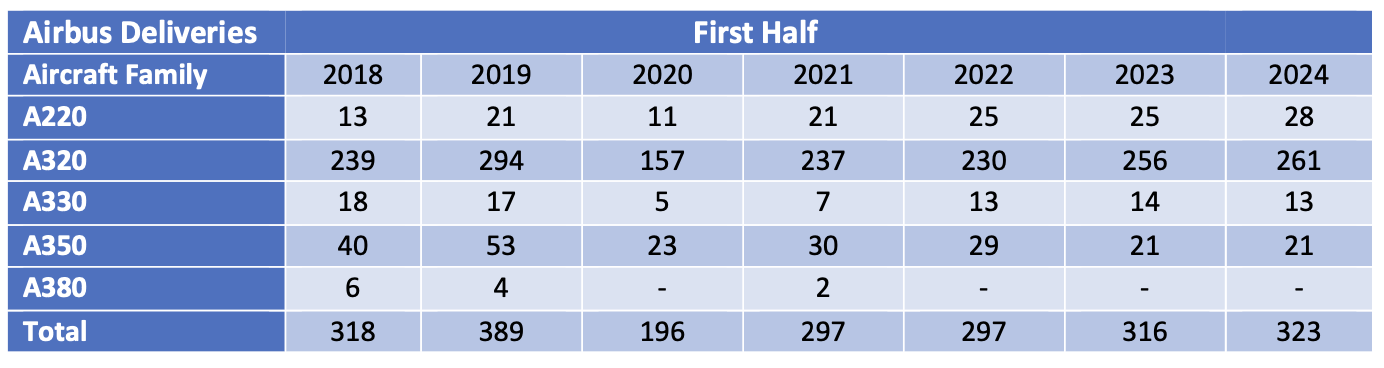

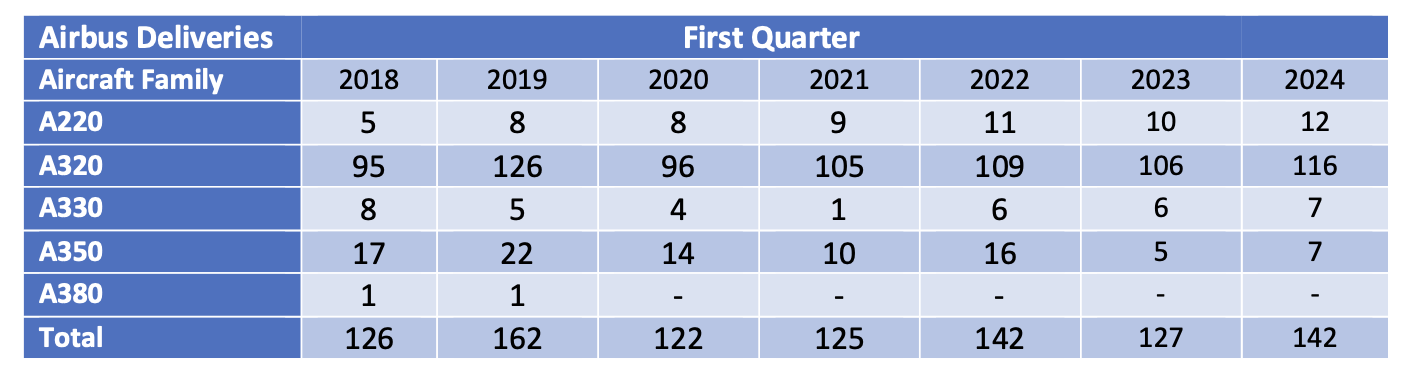

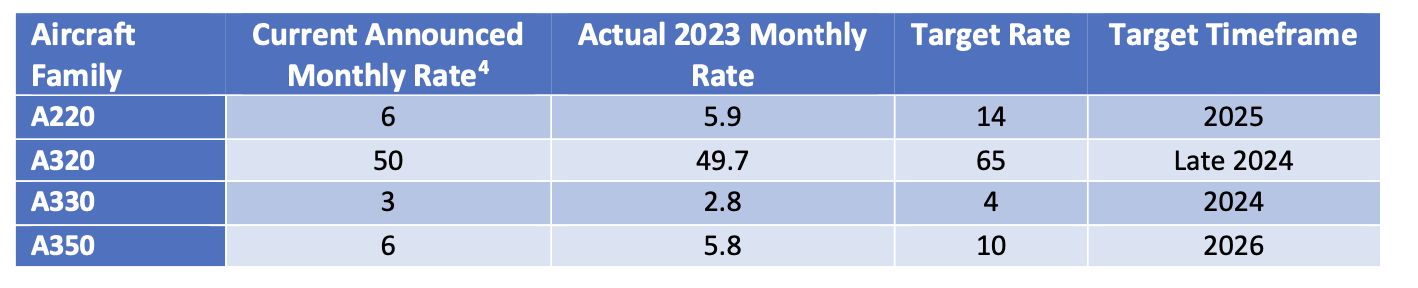

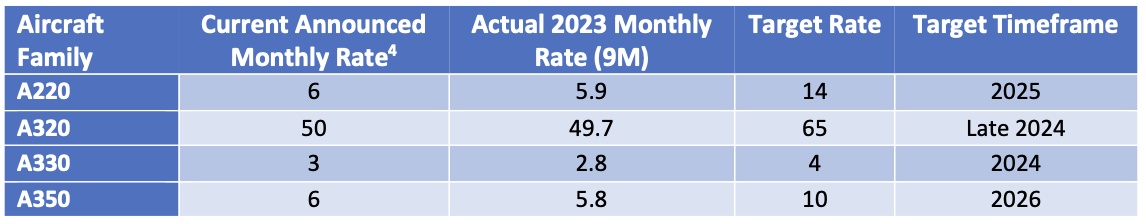

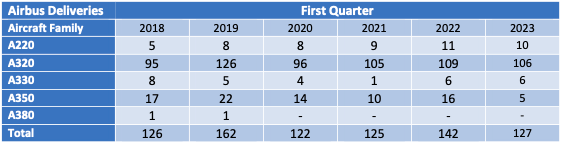

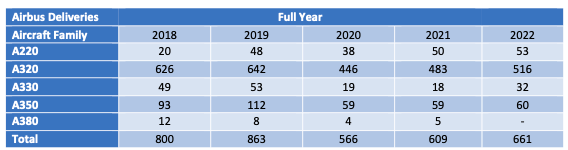

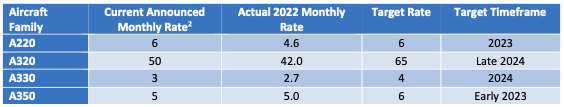

Airbus delivered slightly fewer aircraft in Q1 2025 than in Q1 2024 mainly due to continuing supply chain constraints which were aggravated by the acceleration of some CFM International LEAP engine deliveries into Q4 2024 to meet last year’s delivery target. According to Cirium there is evidence of an increased level of aircraft rolled out of final assembly, but which have not yet flown which indicates that Airbus has a reasonable prospect of meeting its 2025 delivery target of 820 aircraft subject to resolving its supplier issues.

There has been no change in Airbus’s production plans (the current production figures in the table above include some external estimates as well as official Airbus guidance). Where Q1 actual deliveries are lower than current production rates this is most likely due to the typical fall back after the “Q4 rush”.

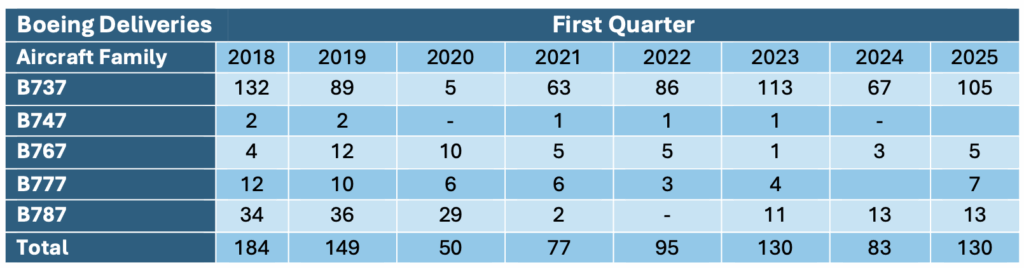

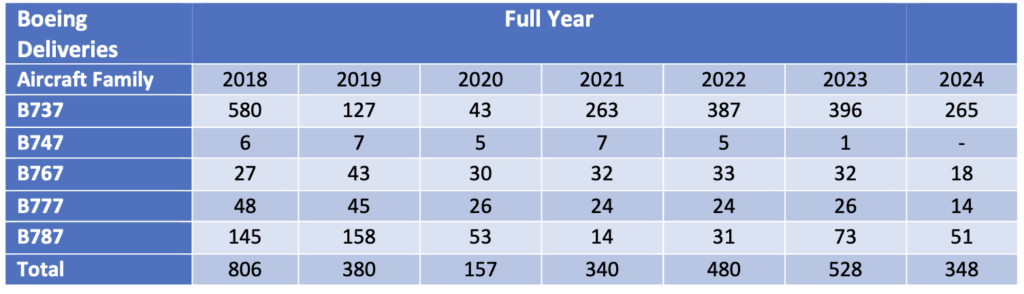

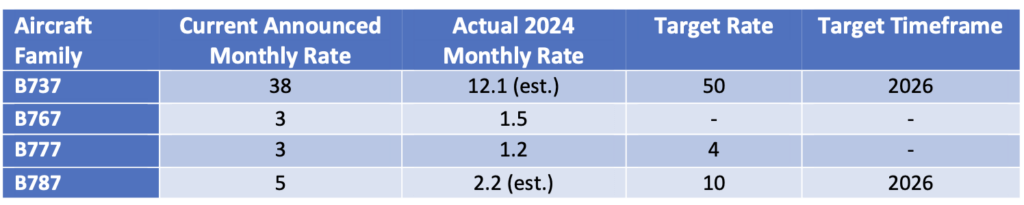

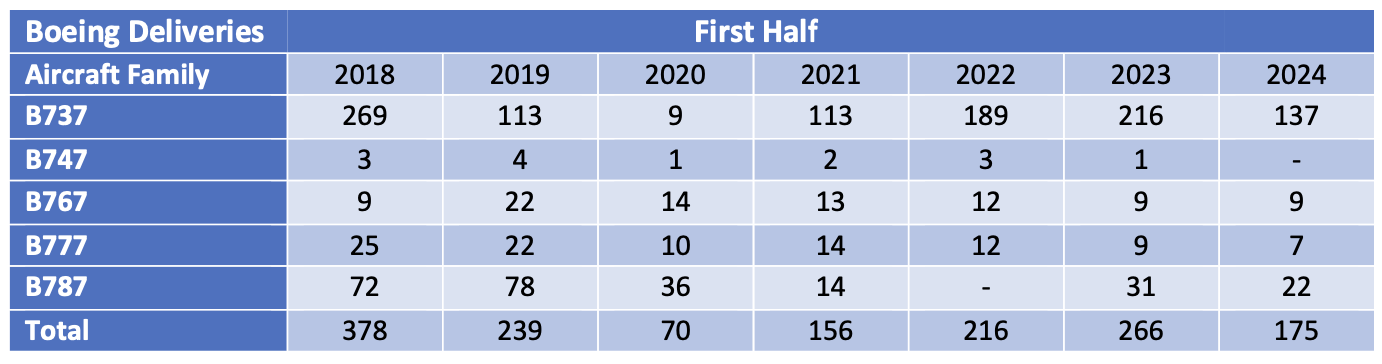

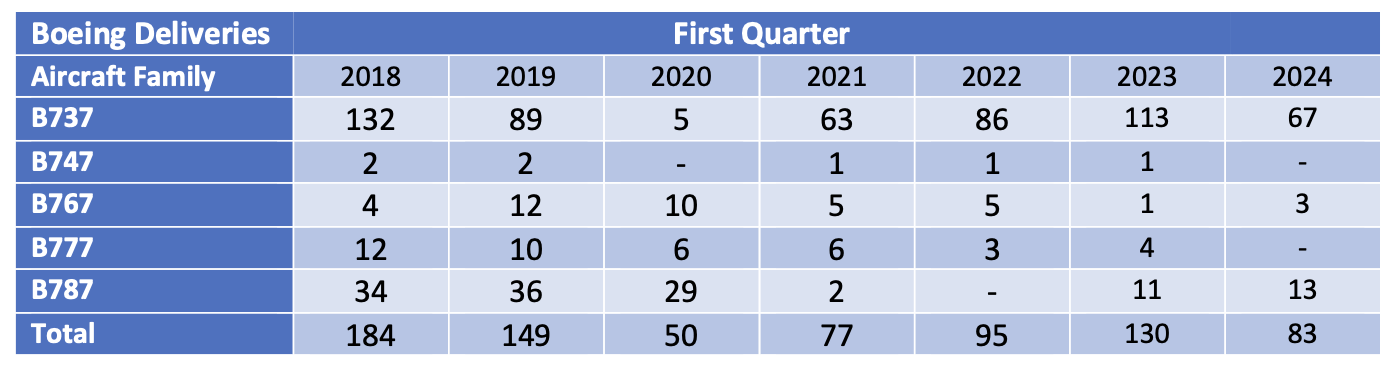

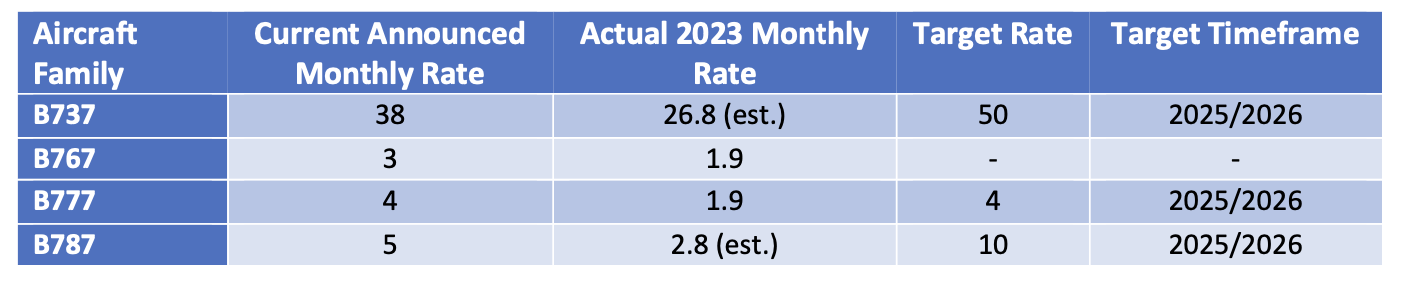

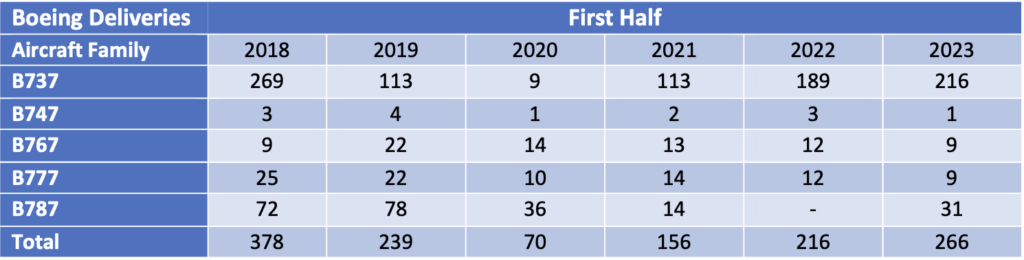

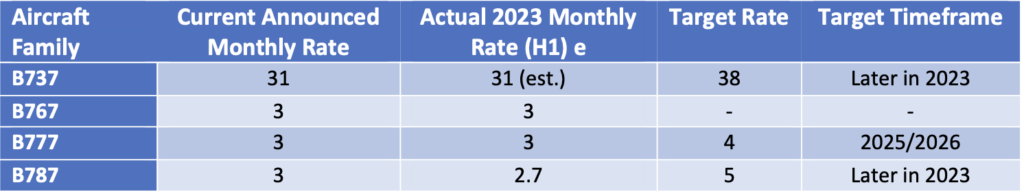

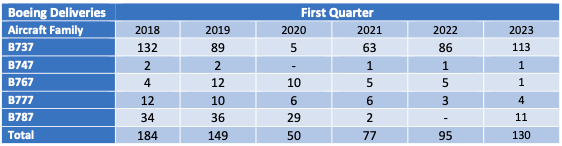

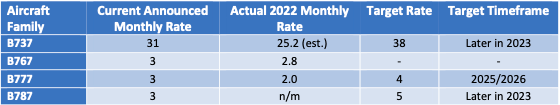

Boeing’s deliveries increased significantly year-on-year although at least some of these were accounted for by reductions in the number of aircraft in inventory. Boeing disclosed a drop of 20 in its B737 inventory in Q1 which we have deducted from Q1 deliveries to arrive at our estimated monthly actual production rate of 28.3. However, our approach relies on incomplete information as the inventory figures quoted by Boeing are in respect of aircraft produced prior to 2023 and there could well be other aircraft in inventory manufactured later. We have made another estimate for the B787 where the Q1 inventory reduction was 5 aircraft although this is subject to the same qualifications as for the B737.

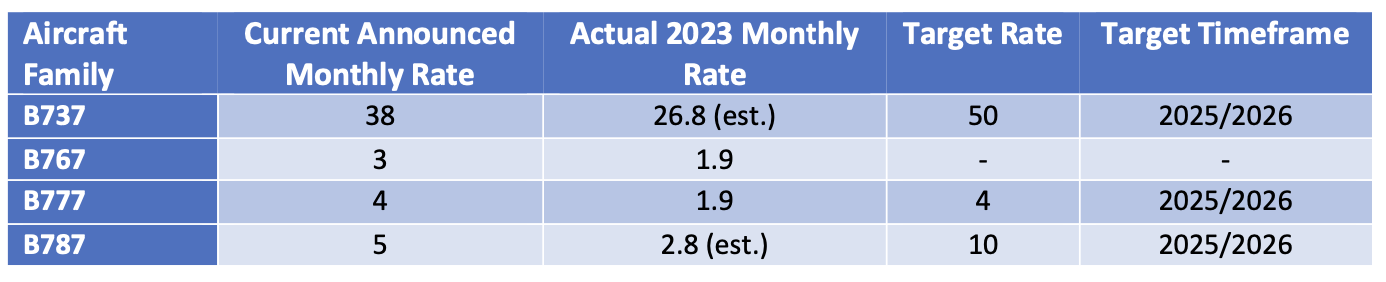

When reporting its Q1 results in April Boeing’s CEO Kelly Ortberg said that the B737 production rate is up to 31 per month and they are working towards the FAA-mandated maximum production level of 38 per month with a medium-term target of 50. The production target for the B787 is an increase from 5 to 7 by the end of 2025 with a further increase to 10 in 2026.

One additional complication for Boeing is the status of aircraft contracted for sale to Chinese airlines who have refused delivery because of tariffs. Boeing said in April that they have 50 B737s and 4 B787s scheduled for delivery to Chinese airlines in 2025. Where an aircraft is not completed there should be relatively little downside for Boeing because other customers will likely take them given the large backlog for both aircraft types. Where the aircraft are completed there would be significant expense and delay to change to a different customer’s specification, but this can be done. Obviously, the situation around tariffs is subject to a lot of uncertainty and this problem may be resolved through political negotiations.

The broader impact of actual and potential tariffs on aircraft manufacturers is very hard to envisage at the time of writing as the global nature of their supply chains creates a lot of complexity compared to e.g., cars. Already certain exemptions for major components have been announced such as the Chinese government’s exemption for CFM engines supplied to COMAC.

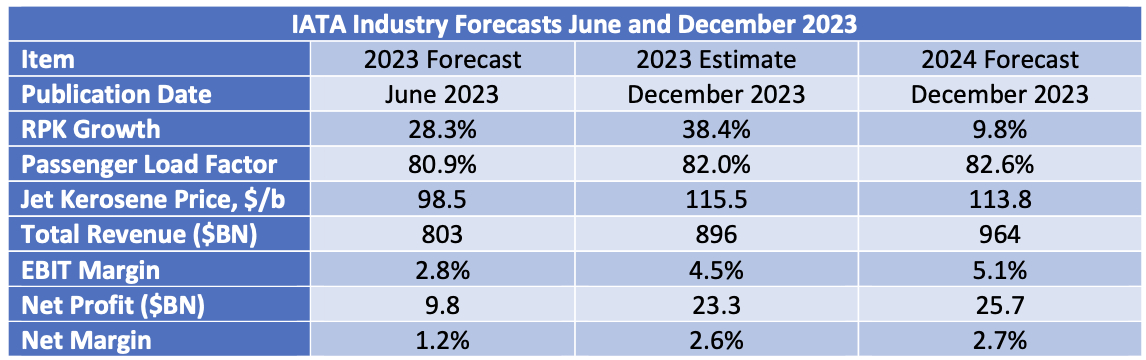

Airline Industry Financial Performance

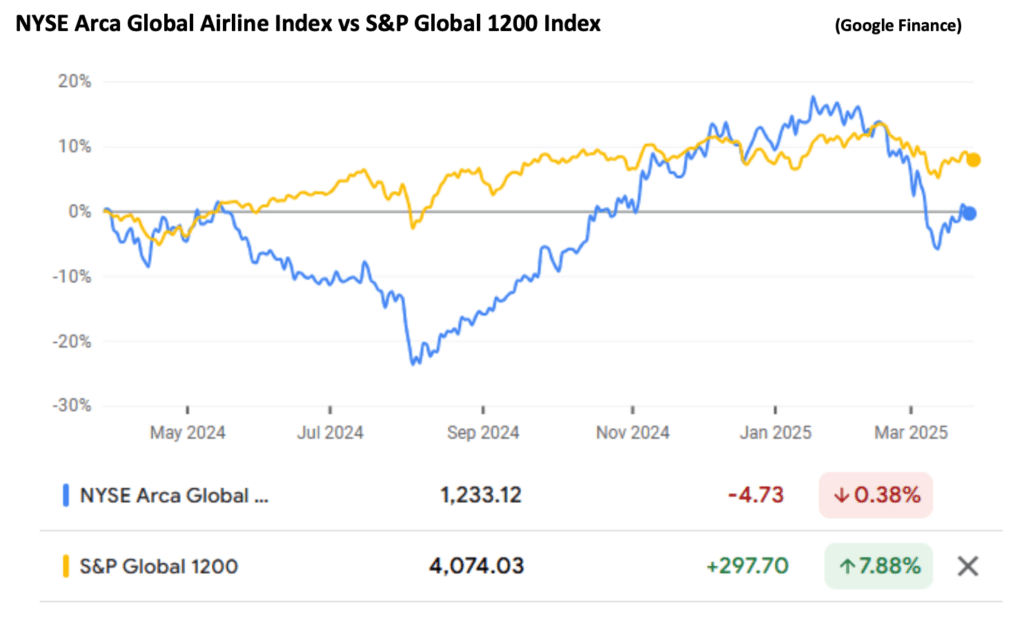

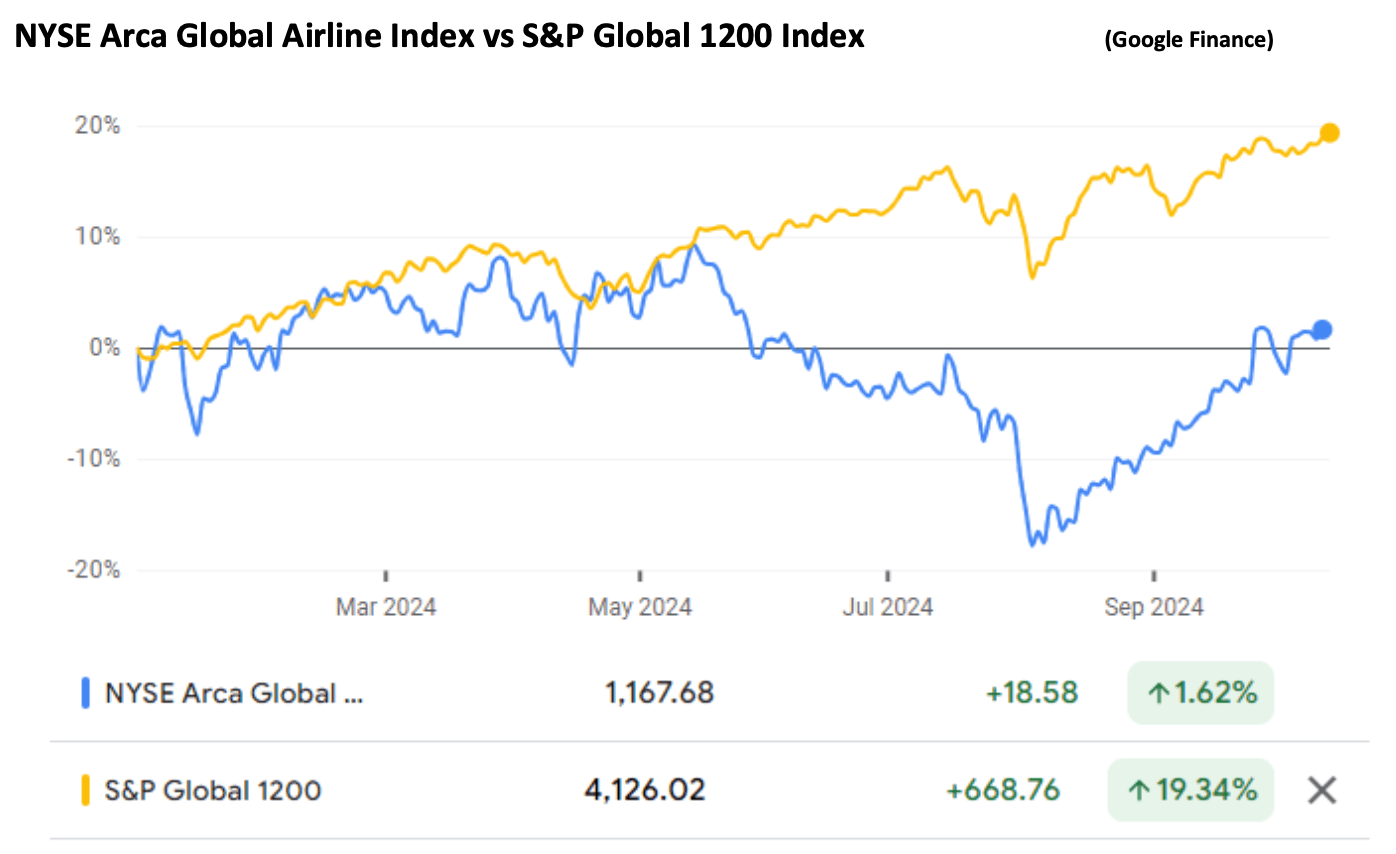

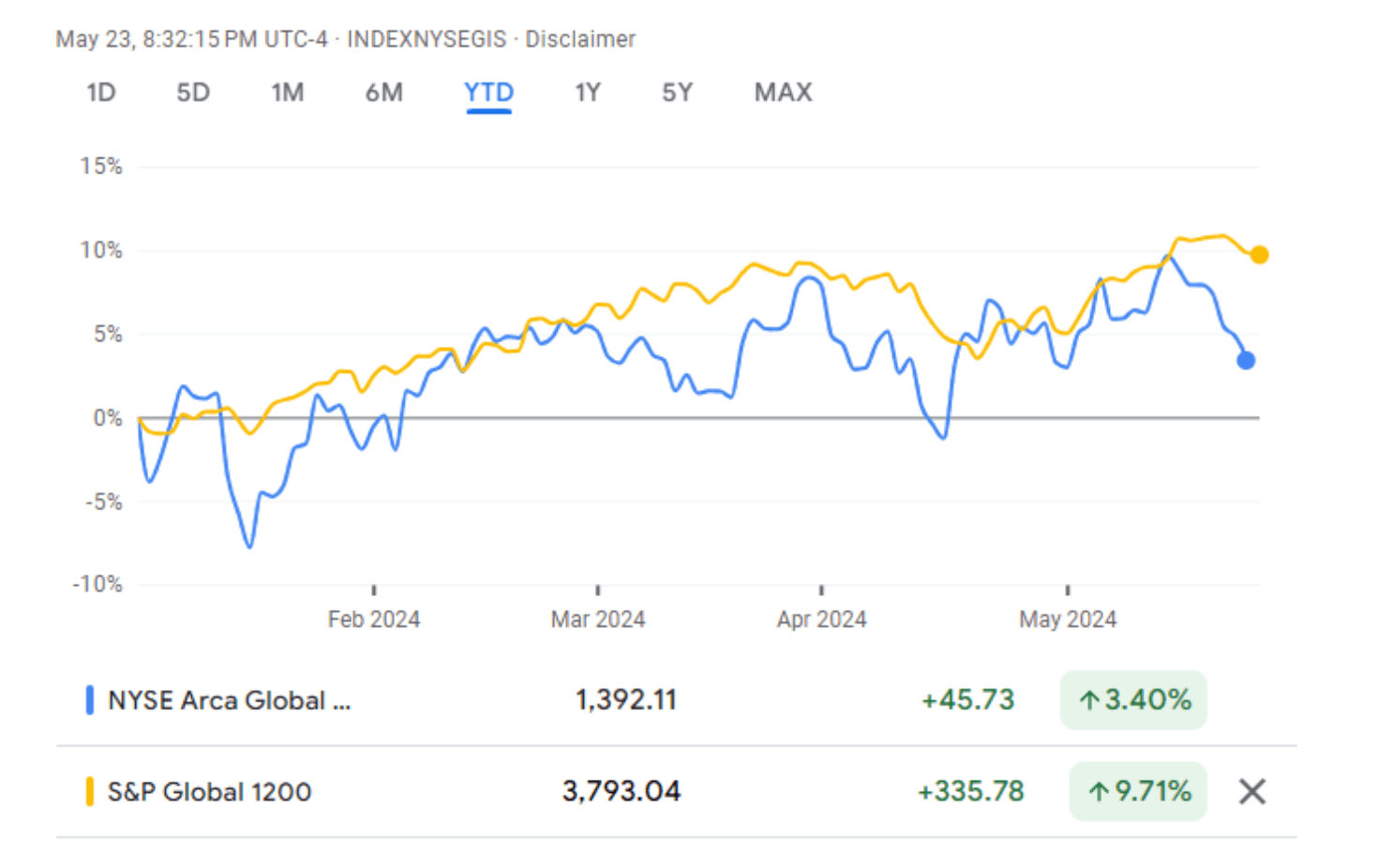

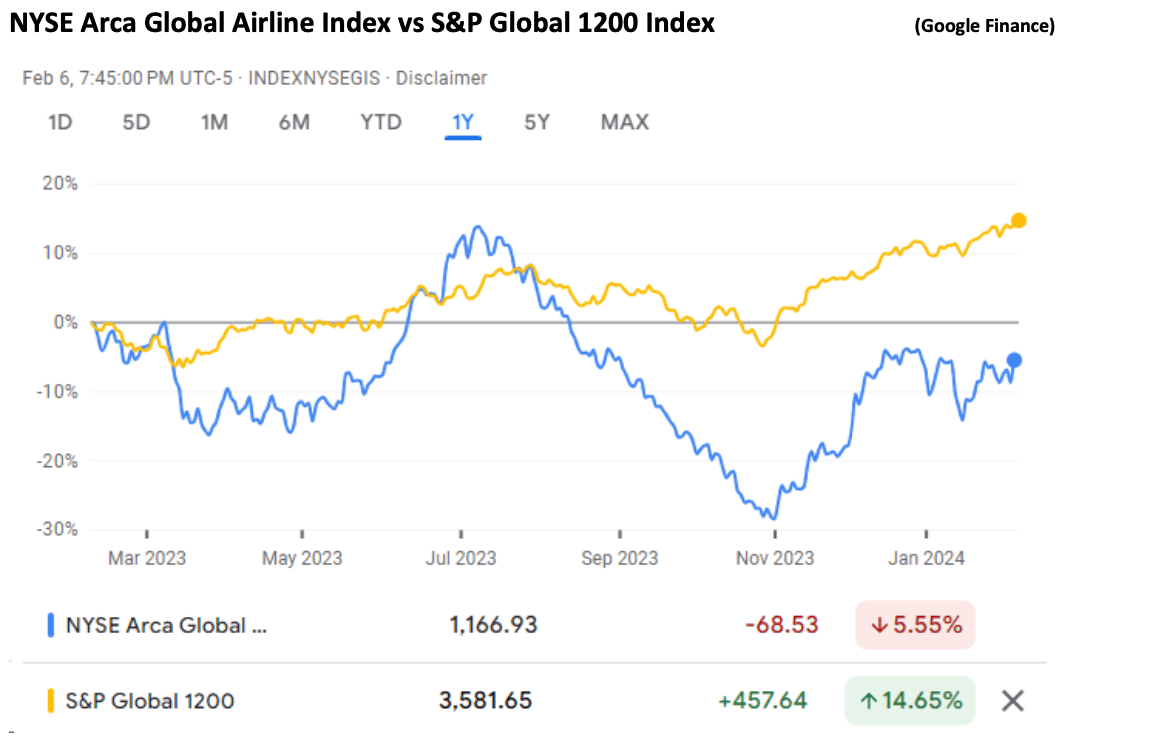

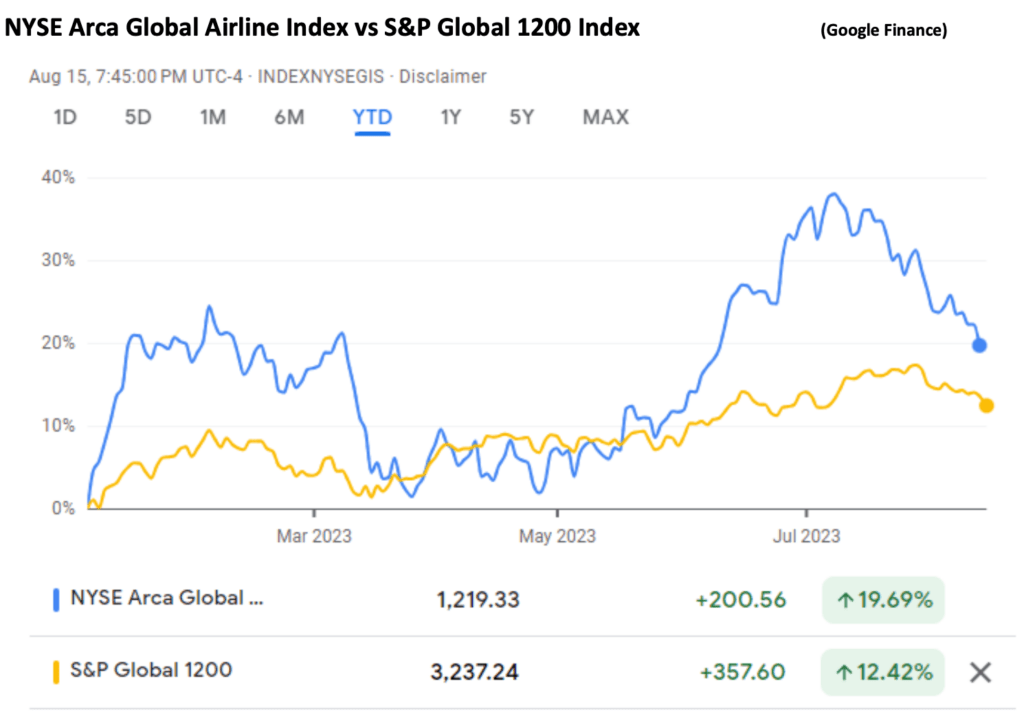

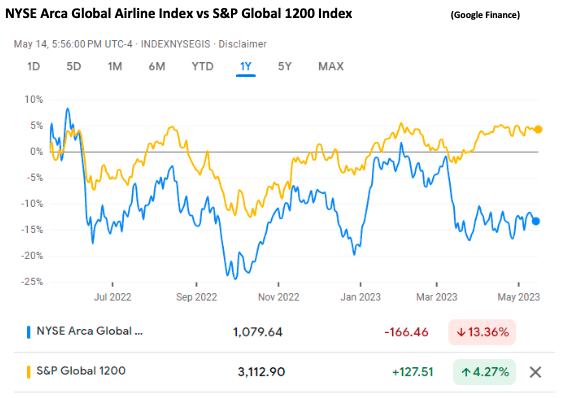

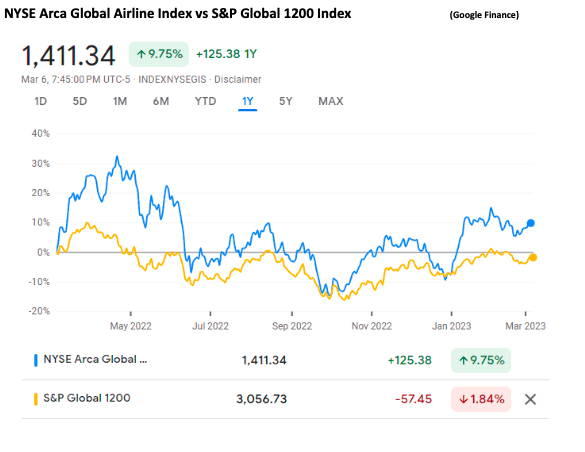

Airline stocks fell more heavily than the overall market in April, which is not surprising as the NYSE Arca Global Airline Index is heavily weighted towards US airlines and the latter have published several profit warnings on the back of weak travel demand.

There had been very few airline failures so far in 2025 until Azul filed for bankruptcy last month. Of the two largest bankruptcies in 2024 Spirit exited from bankruptcy in March and Gol will likely follow in June. Azul’s bankruptcy is another example of how difficult it is to avoid this procedure if all one’s competitors have availed of it (see above). Our historical analysis suggests that there will be more financial distress over the rest of 2025 than has occurred to date.

Appendix – Airline Industry Default Study Methodology

Our study has some limitations mainly driven by practicality. We only cover all airlines that have operated more than 5 passenger jet aircraft at any year end since 1970 according to Cirium Fleets Analyser. This reduces the number of airlines we need to research from 2,914 with no size cut-off to 1,163, but we still cover 98% of the passenger jet fleet by units.

We also limit our statistical analysis in time to start in 1990 because certain key characteristics of the industry changed around this time, notably deregulation and the rise of aircraft leasing as a source of capital. Going back to 1970 would lower our estimated average annual default rate but we believe that conditions prior to 1990 were not comparable.

We due diligence the history each airline based on public sources and record defaults captured by this research. We also add defaults for airlines in emerging market countries that experience sudden fleet reduction as the events caught by this rule may well represent informal defaults that occur without court proceedings. Our final output is adjusted defaults which combines both research-based and rules-based defaults after eliminating mergers and double-counts. The number of adjusted defaults is c.50% higher than for research-based defaults alone. We measure adjusted defaults based on the number of airlines and the number of affected aircraft. Our airline fleets data source is Cirium Fleets Analyzer.

- Airline population limited to airlines with 6 or more aircraft at year end during study period – There are 1,163 airlines that had a fleet of 6 or more aircraft out of 2,914 total airlines

- Historic default events are Research based, or Rules based.

- Research based events are derived from study of relevant academic/government publications and online resources (Airlines for America, Wikipedia)

- Single airlines can default on multiple occasions

- Cessation/suspension of operations assumed to result in default unless there is clear evidence that this was not the case

- Every single airline with its own licence (“AOC”) counts as a default e.g., both the LATAM and Avianca groups filed for bankruptcy in 2020, and as a result each of their subsidiaries, which also had distinct licences, experienced a default and is counted separately

- Research based events are derived from study of relevant academic/government publications and online resources (Airlines for America, Wikipedia)

- A Rules based event only occurs for airlines based in an emerging market country (per World Bank classification) where default processes are assumed to be more informal. A Rules based event occurs if:

- An airline with 15 or more aircraft has a year-on-year fleet reduction of 20% or more, or

- An airline with less than 15 aircraft has a year-on-year fleet reduction of 3 or more aircraft

- Some events are eliminated if research shows there clearly was no default i.e. Copa Airlines Colombia

- An airline cannot default two years in a row e.g. bankruptcy shortly followed by cessation of operations in the following year is treated as a single default

- Adjusted Defaults by Airline are the combination of Research Based and Rules Based events which are filtered to eliminate mergers and duplication of events.

- Adjusted Defaults by Aircraft take the fleet size the year before the defaults occurs, not the max fleet size for the airline.

[1] Although 2020 was a record year for defaults there were also significant rent deferrals granted by lessors to airlines which can reasonably be considered as additional payment delinquency that is not captured by our methodology. As most of these deferred amounts have been repaid this was a strong case of enlightened self-interest on the part of the lessors, although this is clearer with hindsight than it was at the time.

[2] RPKs is the acronym for revenue passenger kilometres, which is the product of the number of paying passengers times distance flown.

[3] ASKs is the acronym for available seat kilometres, which is the product of the number of available seats flown times distance flown.

Disclaimer

Industry Update Q4 2024

- Special Topic – Aircraft Economic Life

- Macro-Economic Background

- Traffic and Aircraft Demand

- New Aircraft Supply

- Airline Industry Financial Performance

Where are all the early retirements? Is it different this time?

Aircraft Economic Life

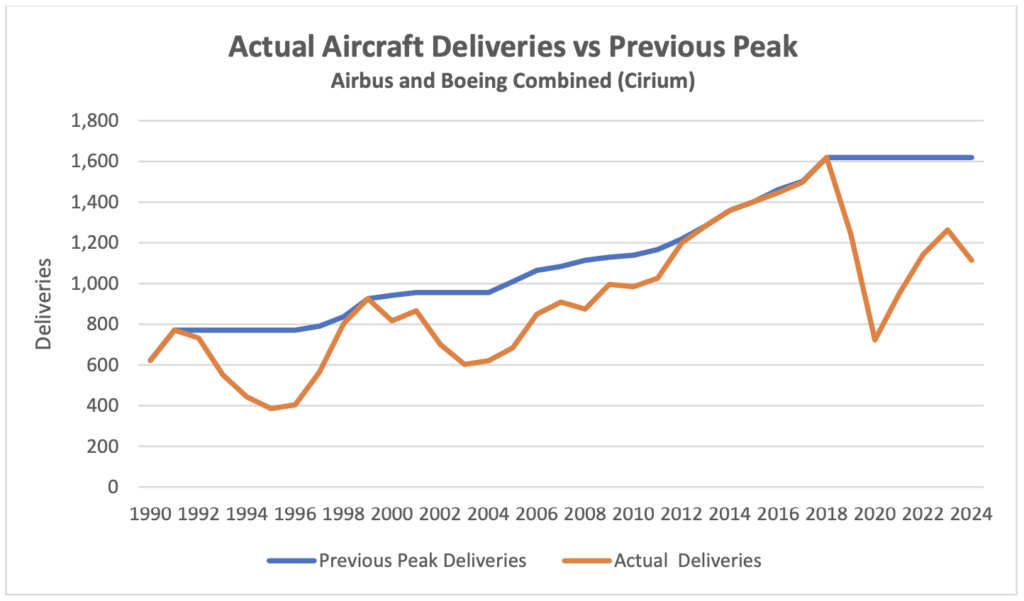

As we discuss in more detail below 2024 was another very weak year for new aircraft deliveries. The recent decline is unprecedented as the delivery trough was 723 aircraft, 45% of the prior peak of 1,619, but on this metric, it is not much more severe than the decline of the early 1990s where the trough was 385, 50% of the prior peak of 771 (these figures include McDonnell Douglas although it had not yet been acquired by Boeing).

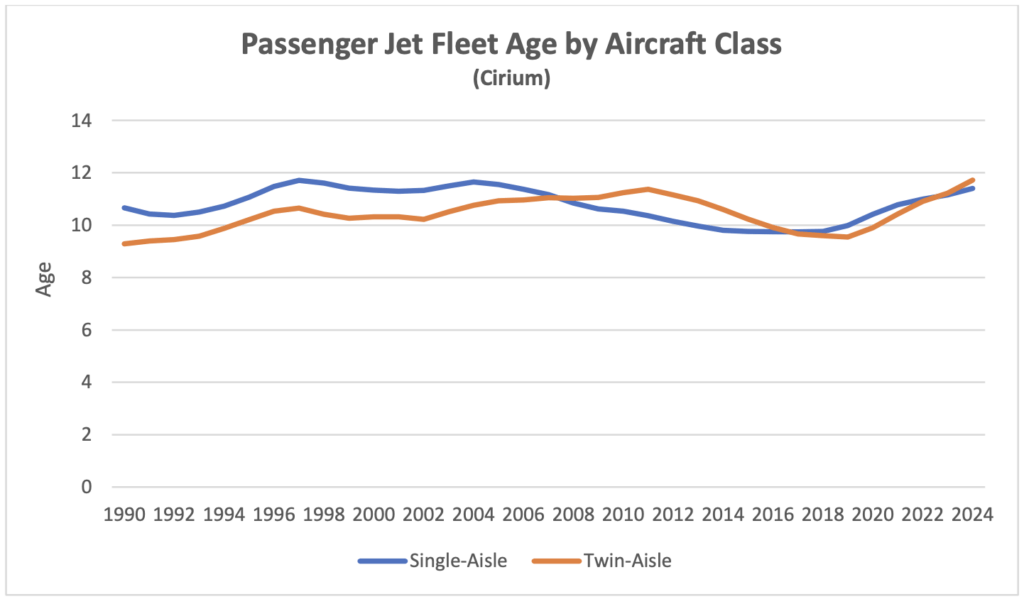

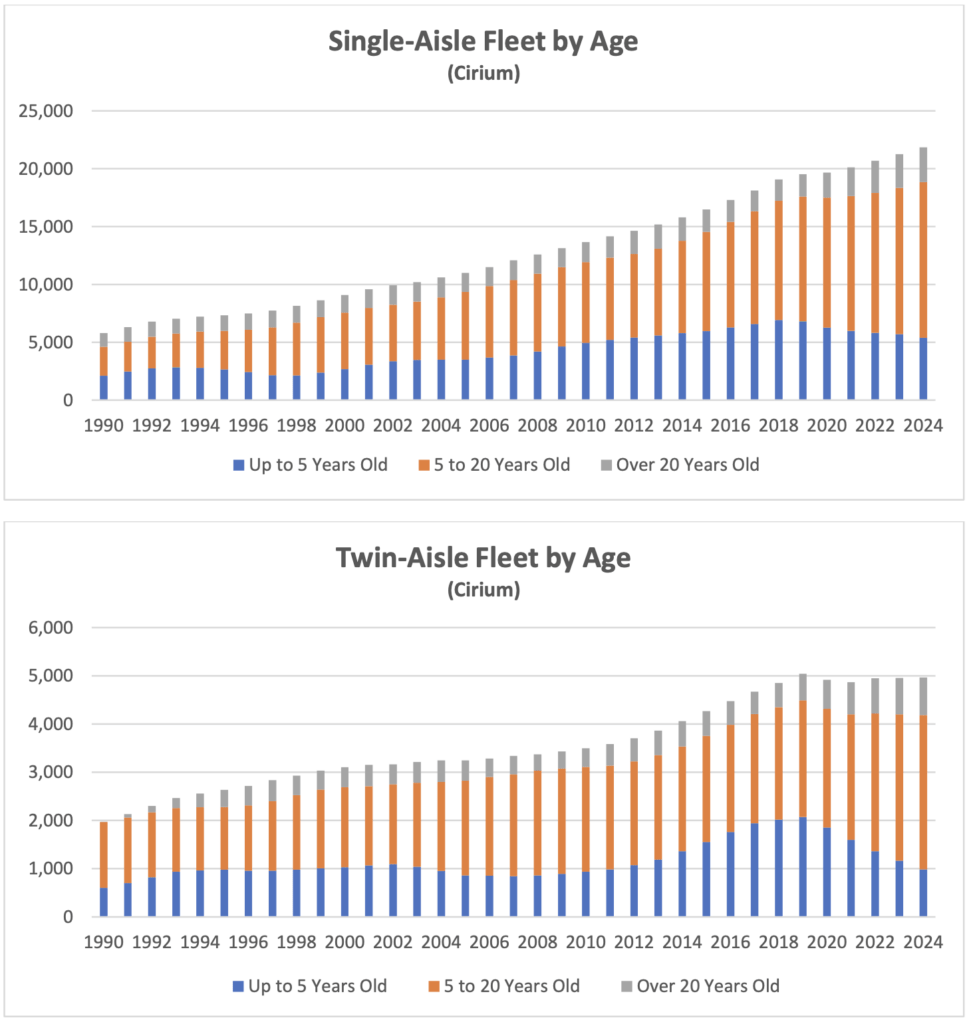

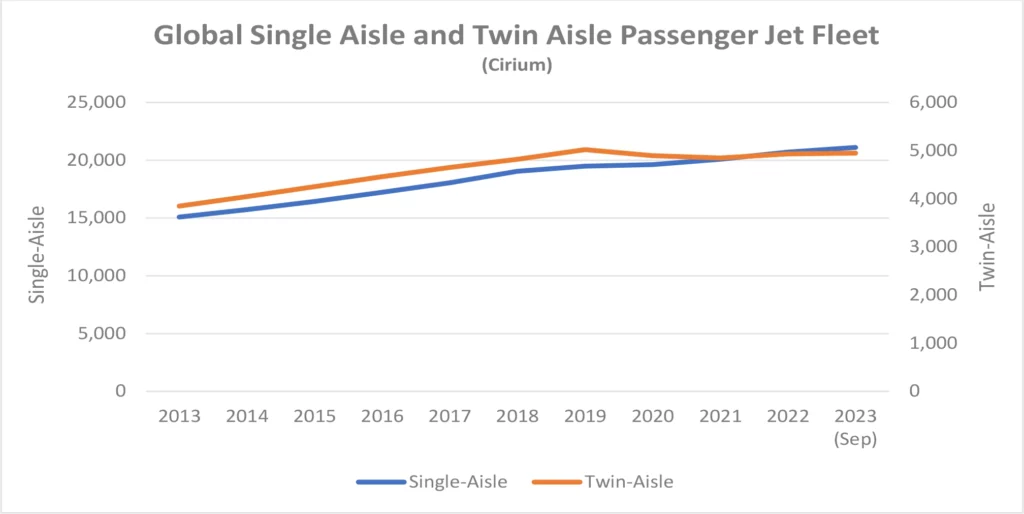

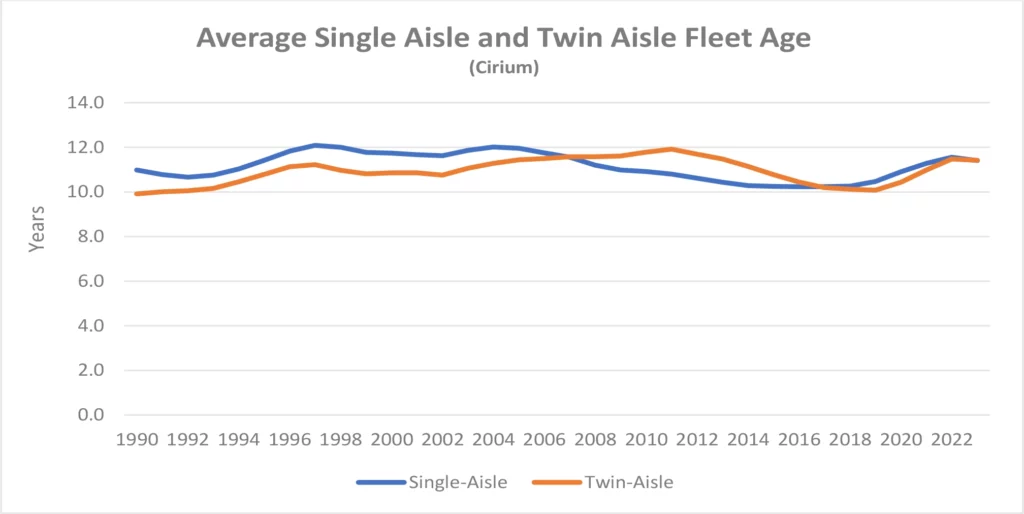

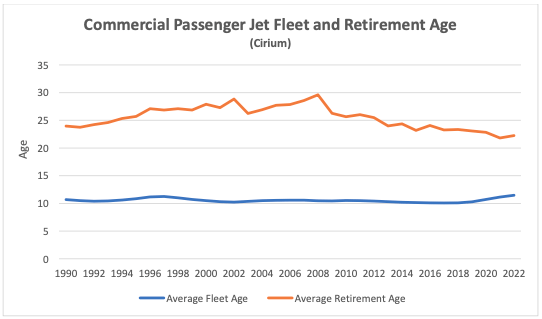

It took until 1998 for deliveries to exceed the level achieved in 1991. We are now in 2025, which is also 7 years after peak deliveries, but we are probably still some years away from the level achieved in 2018. There is strong evidence of increased demand for used aircraft because of the shortfall in new capacity and as one would expect the average age of aircraft has increased (the charts below refer to passenger aircraft only – although some passenger aircraft have their lives extended by conversion to freighter and other uses the numbers are relatively small).

As one might expect a low level of new aircraft deliveries has led to an increase in average fleet age, which is now as high as it has ever been since 1990 for both single-aisle and twin-aisle aircraft (twin-aisle average aircraft age has gradually increased relative to single-aisle aircraft as the latter had a “head start” with entry into service 6 years before the first twin-aisle delivery).

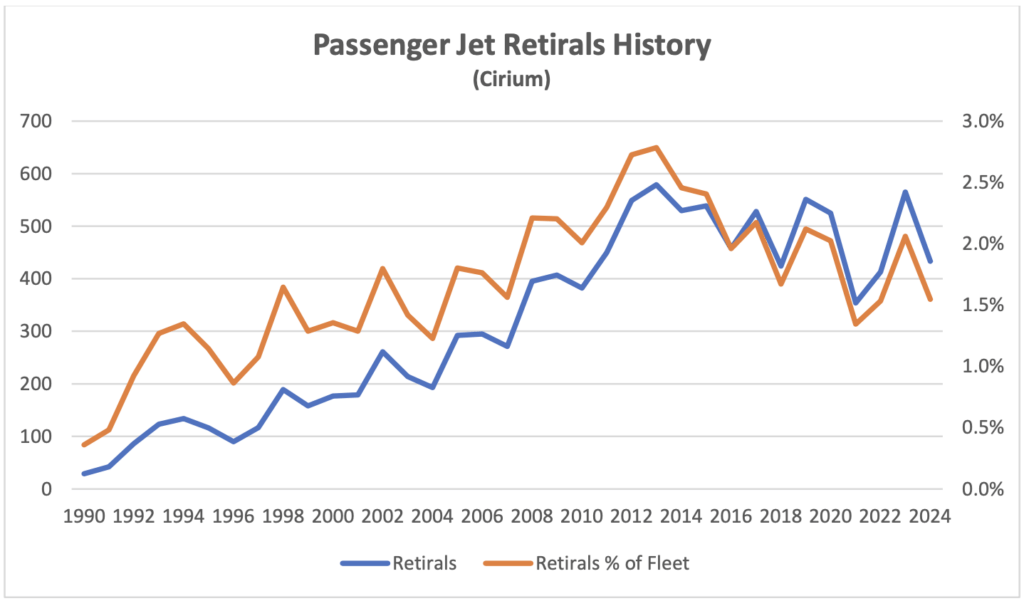

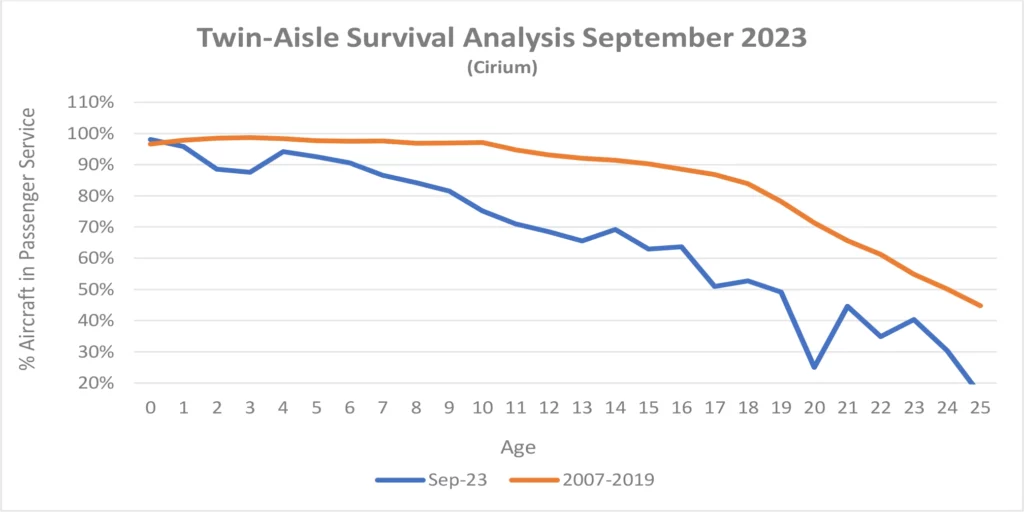

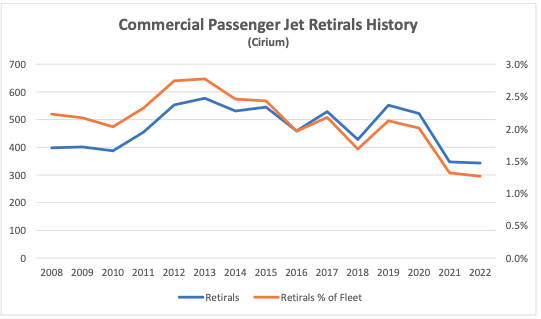

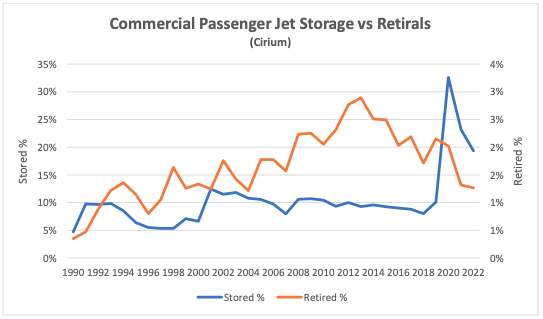

This increase in fleet age suggests it’s worthwhile to look at trends in aircraft retirals as these should be related. This raises the question of what the most useful data is to look at. If one considers the number of aircraft retirals, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of the world fleet, the results do not show any particular trend after 2010 – the increase prior to 2010 is largely due to the maturing of the world fleet as hardly any aircraft had been retired prior to 1990 other than obsolete early technology types.

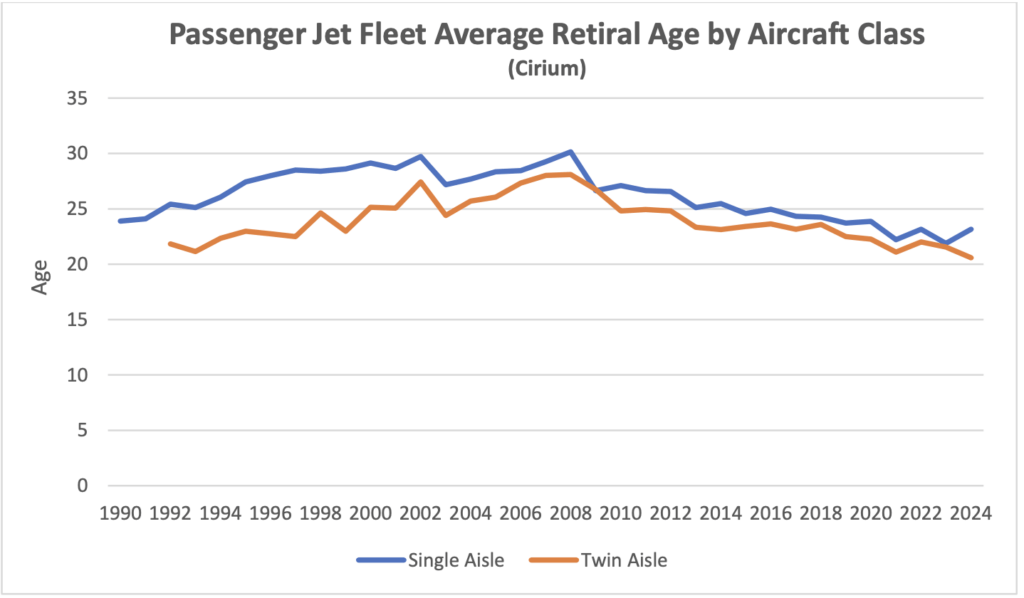

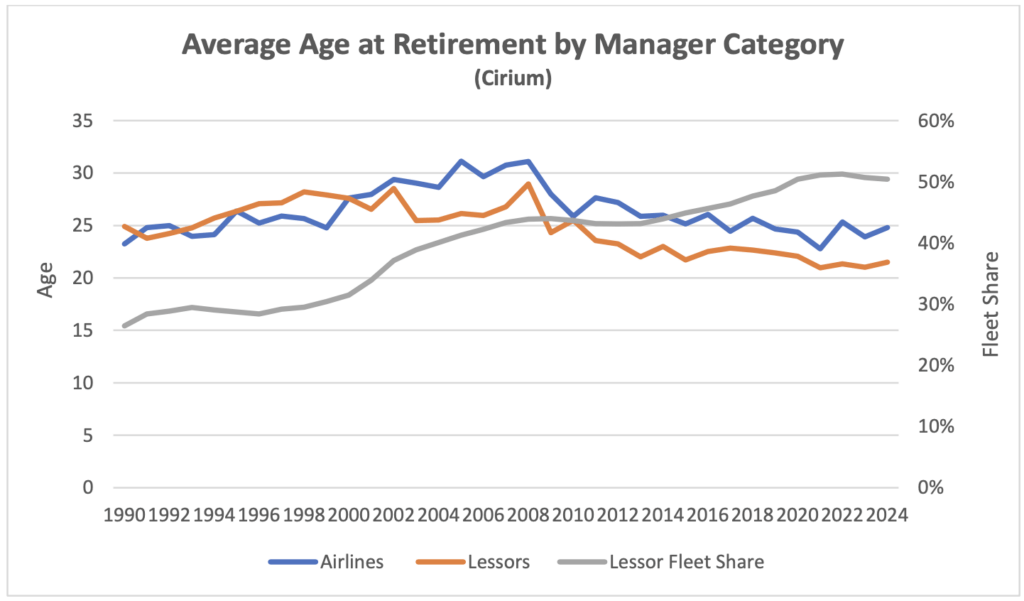

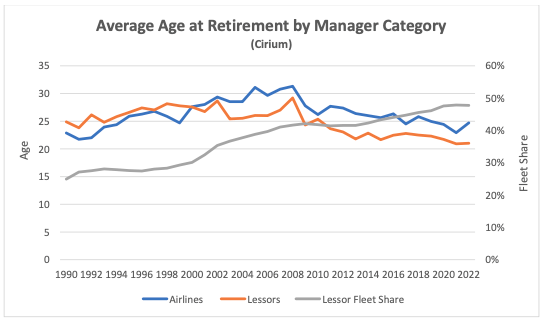

A more helpful way to analyse retirals data is to look at average age at retiral where a much stronger pattern emerges with a “plateau” from around 2001 to 2008 with a gradual decline thereafter. This helps to explain why retiral volumes are volatile – if retirement ages only change very gradually but the level of historic new aircraft delivery volumes was volatile it follows that retiral volumes will also be volatile. It is also noteworthy that retiral ages are consistently higher for single-aisle aircraft because they are less exposed to several important risks especially improvements in technology which have a greater relative impact for aircraft that fly long-haul.

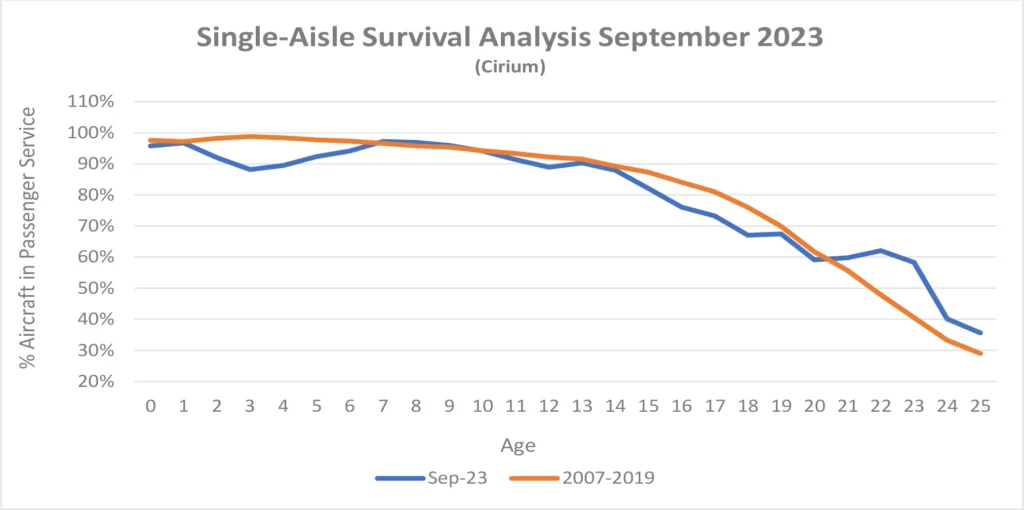

The impact on retiral age of reductions in new aircraft deliveries in the early 1990s and from 2019 has been very different. In the 1990s there was a sharp increase in age at retiral which one would expect given the drop in deliveries and increase in average fleet age. Although both these conditions have also prevailed since 2019 the long run drop in average age at retiral that started in 2008 has broadly continued.

We believe that the most important cause of this difference is the increased share of the fleet owned by lessors. As investors seeking to maximise the present value of their assets, lessors are typically reluctant to commit additional capital to redeploy an aircraft with a new airline operator once it reaches c. 18 years old because there is very little time in which to recoup this investment.

Lessors consistently retire aircraft at younger age than airlines as the redeployment cost issue does not arise for the latter.

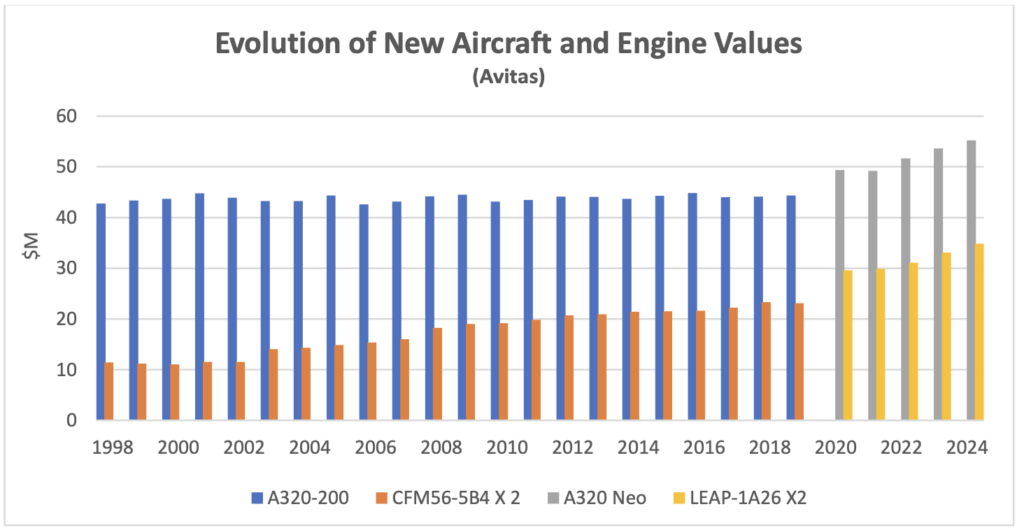

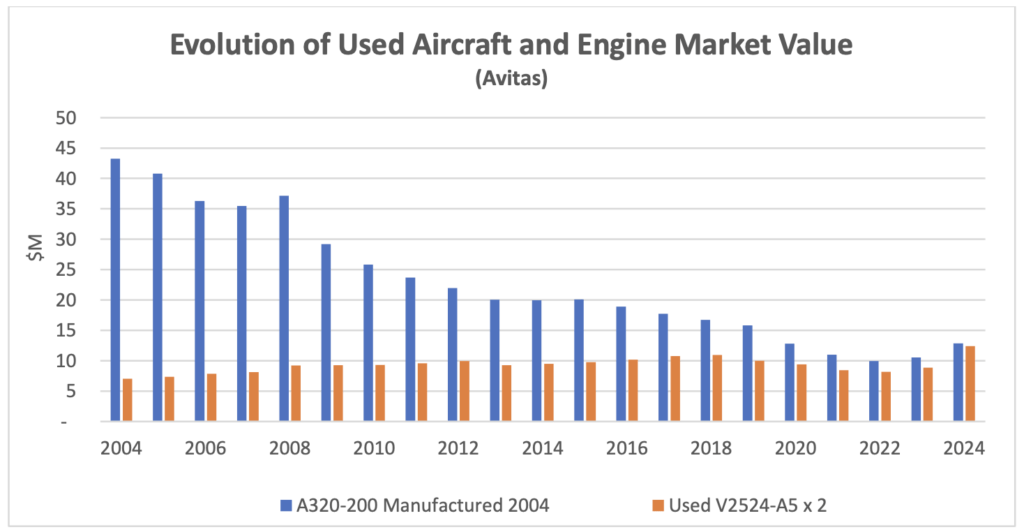

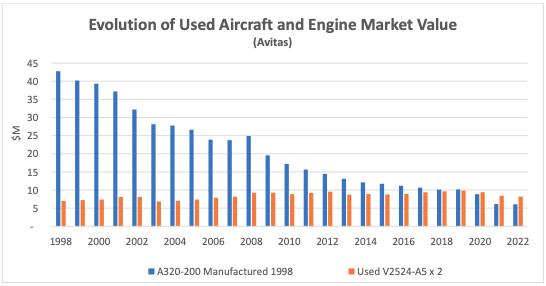

The key factors affecting a lessor’s decision whether to reinvest are the break-up value of the aircraft and the cost of redeployment. Break-up values have been increasing relative to value in use for many years, mainly because the value of an aircraft’s principal components, its engines, have been increasing in relative terms. In 1998 engines accounted for c. 25% of the cost of a new aircraft whereas in 2024 the proportion was over 50%.

Break-up value is largely driven by engine values, which are in turn very dependent on the value of engine spare parts. The engine manufacturers have an effective monopoly on new spare parts and have historically enjoyed significant pricing power until c.10 years from when the relevant aircraft type ceases production. For many years engine spare parts prices have increased by 6-7% p.a. while new aircraft prices have increased by 1.0-1.5% p.a.

These trends have created a situation where stand-alone engine values can exceed an aircraft’s value including engines well before the point where the aircraft has reached its potential service life. Where an existing airline operator is happy to extend a lease, a lessor will have very little cost associated with extending its revenue stream and is likely to choose this option so not all aircraft will be broken up at the same age.

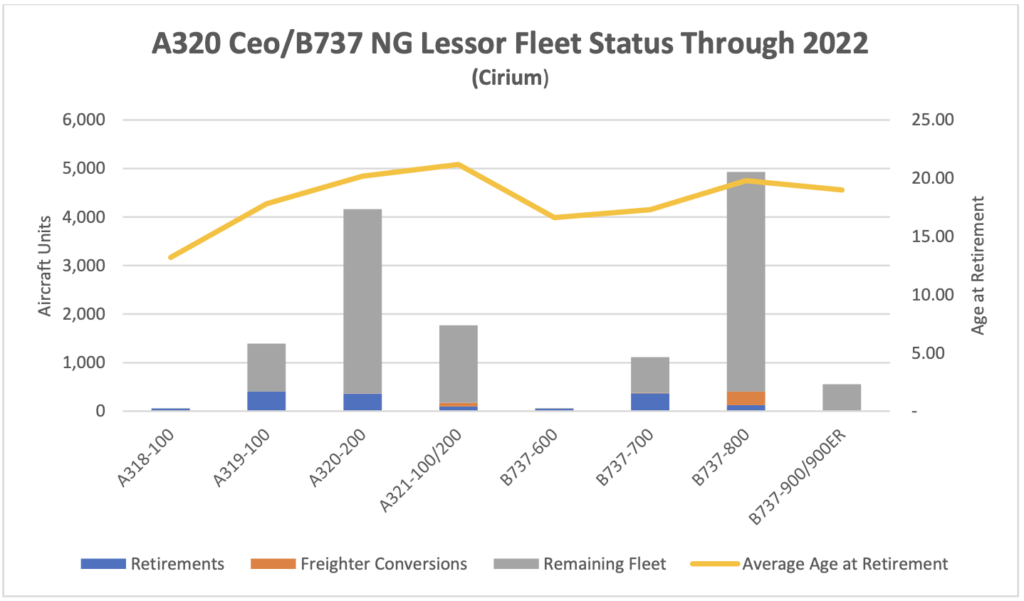

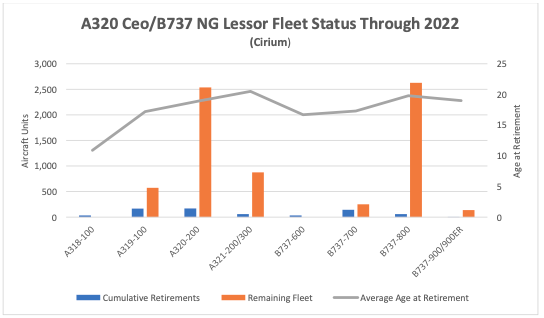

One way to test the importance of break-up values is to look at what has happened with different members of the A320 Ceo and B737 NG families. Break-up values are very similar for all family members, but the larger models command higher rents, so if break-up values matter, we should expect to see smaller types retired earlier and in greater numbers. The chart below shows how the different family members have performed through 2024 and supports this view. Smallest to largest aircraft types are presented left to right.

We believe the “pull factor” of attractive break-up values has been the main driver of reduced age at retiral for single-aisle aircraft but not for twin-aisle aircraft. It should be borne in mind that not all engine types have the same level of marketability. The CFM56 and V2500 engine types associated with the A320 Ceo and B737 NG aircraft families[1] are overhauled by several different market participants who compete to buy used engines. Most twin-aisle aircraft engines are subject to a total care agreement with the engine OEM which also dominates maintenance activity, so market dynamics are much less favourable for engine owners.

There are also major differences in relative redeployment costs because twin-aisle passenger cabins are more heavily branded and customised. A 12-year-old A320-200 with an Avitas market value of $22M would be very unlikely to cost more than $1M to redeploy, whereas an A330-300 of the same age with an Avitas market value of $31M could cost anything from $15M to $25M. Based on this we believe that falling ages at retiral for twin-aisle aircraft are more a function of “push factors”.

Whatever the causes the fall in deliveries and the continued reduction in age at retiral has created a very unusual distribution of aircraft by age compared to any time since 1990. Aircraft aged 5 to 20 years old account for an unprecedented fleet share and if anything, this is likely to increase.

These unusual circumstances have not led to a “capacity crunch” so far. This is mainly because global RPKs remain well below their long-term trend (see our Industry Update for Q1 2024 Traffic Growth Outlook). Airlines have been very keen to extend leases as much because of uncertainty surrounding the timing of future deliveries as because of any immediate shortage of capacity.

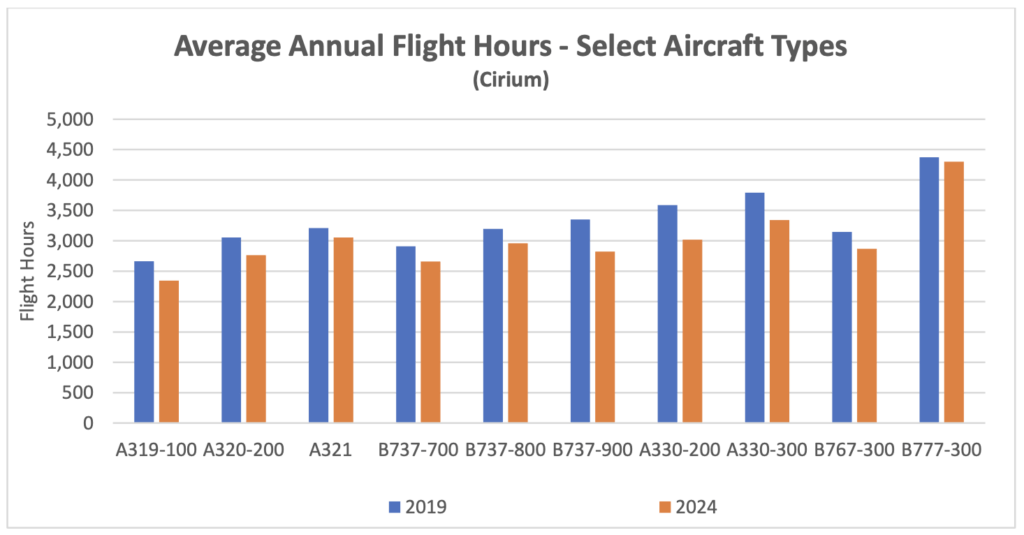

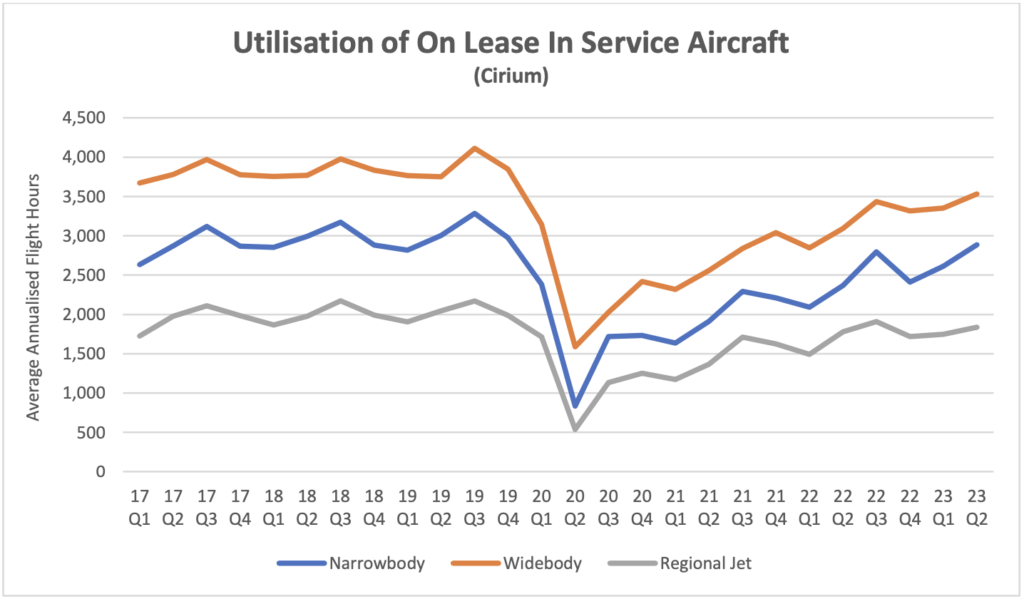

As a cross-check on the fleet data in the charts above we have looked at the utilisation of the aircraft types that are key constituents of the 5–15-year-old fleet. In all cases flight hours are lower than in 2024 than in 2019 with a greater gap for twin-aisle aircraft. A modest reduction in flight hours should be expected as these aircraft types were largely out of production around 2019 so on average, they were 5 years older in 2024 and aircraft productivity reduces with age. Load factors also influence aircraft productivity, and these were slightly higher in 2024 compared to 2019 (see below). To conclude it seems likely that either a continuing shortfall in new aircraft deliveries or a recovery in traffic towards its long-term trend (or a combination of the two) could lead to a significant tightening in the aircraft market.

Macro-Economic Background

The IMF’s January 2025 update to its World Economic Outlook had very similar projections for global GDP growth as in October 2024. The chart below compares the 2024 forecast with its three most recent predecessors. The forecast horizon moves forward each year, so it is helpful to create indices that help visualise the rate of change – obviously steeper is better. The October 2024 forecast was notably more positive than the previous two years. The next full WEO will be published in April 2025, and it will be interesting to see if their view has changed given the threat of significant disruption of international trade.

Economic growth is a key driver of long-term growth of air travel. However, since early 2020 its impact has been overshadowed by the fall and recovery in traffic associated with the pandemic. In time the influence of overall economic conditions on air travel is likely to reassert itself, but industry forecasts published by Airbus, Boeing and IATA assume much higher rates of traffic growth than GDP growth over the rest of the 2020s as the former catches up to its long-term trend (see our Q1 2024 Industry Update for a more detailed discussion).

The US Dollar has recently surpassed its previous 2022 peak, creating pressure for airlines outside the US for dollar-denominated costs such as fuel, aircraft rents and aircraft spares. The price of jet fuel has remained volatile, but it has continued its gradual decrease from February 2024. This reduction has mainly been driven by a reduction in the “crack spread” from c.$30 to less than $17.

Another indicator that is potentially important to aircraft investors is the breakeven inflation rate on US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). This indicator measures inflation expectations and it matters because used aircraft values are strongly influenced by the cost of new aircraft and over time this cost is linked to US Dollar inflation. In the short term this linkage is driven by escalation clauses in aircraft purchase contracts and in the long term by the general input cost environment for the aircraft manufacturers. The chart below compares the breakeven rate for 10-year and 5-year TIPS.

Although medium or long-term inflation expectations have never gone higher than 3.5%, actual inflation experience has been much higher in the last few years. This has led to higher appraised values for new aircraft. If tariffs are applied to aircraft and/or aircraft components this is likely to increase the cost of new aircraft.

Traffic and Aircraft Demand

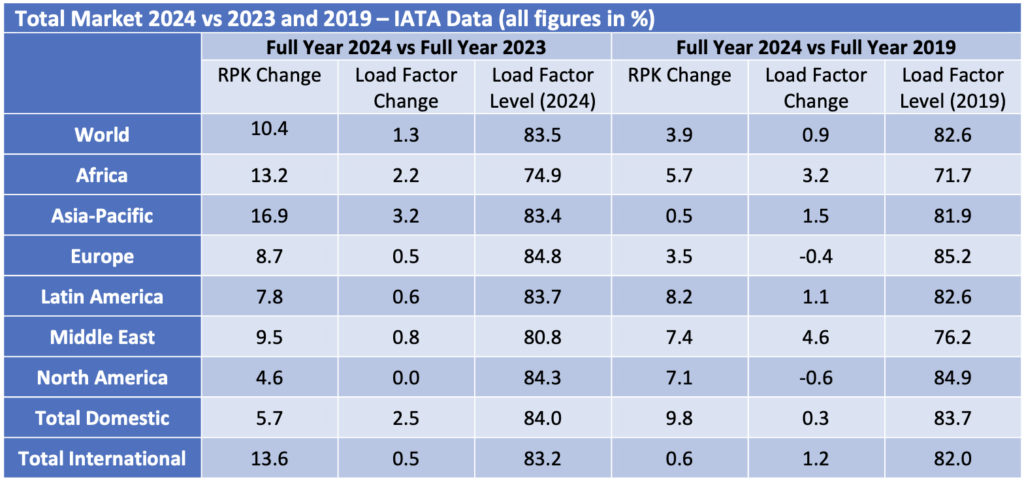

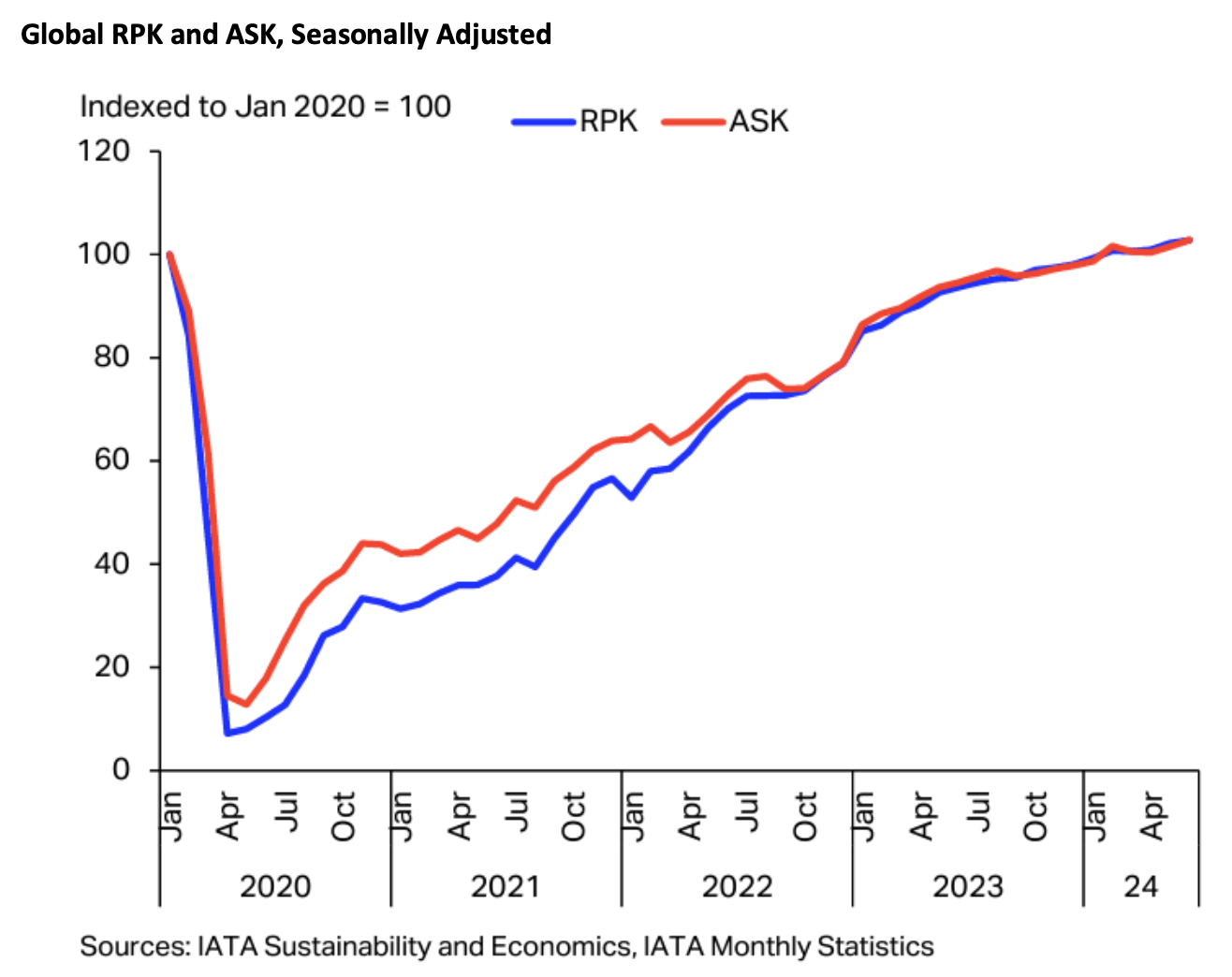

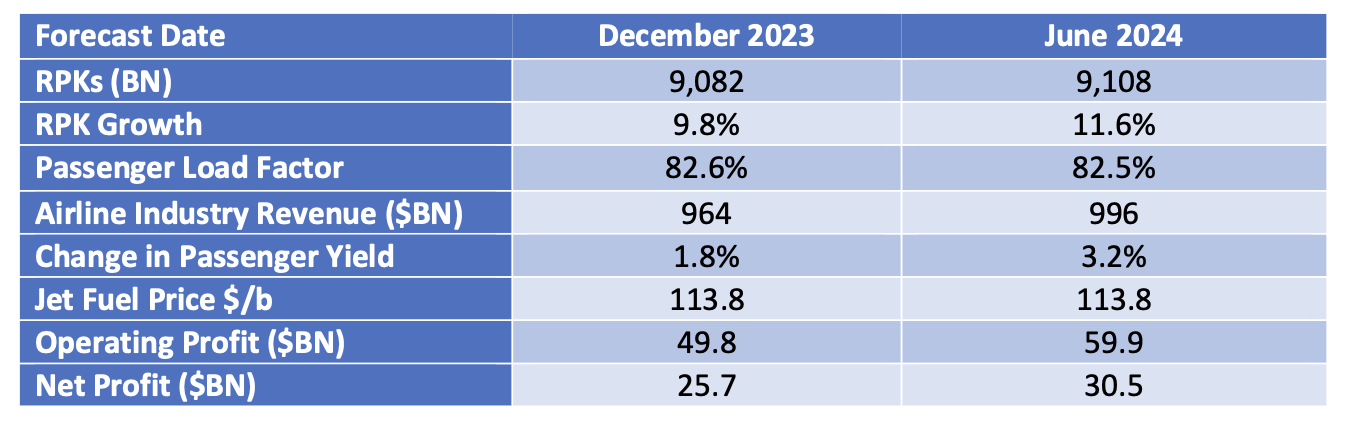

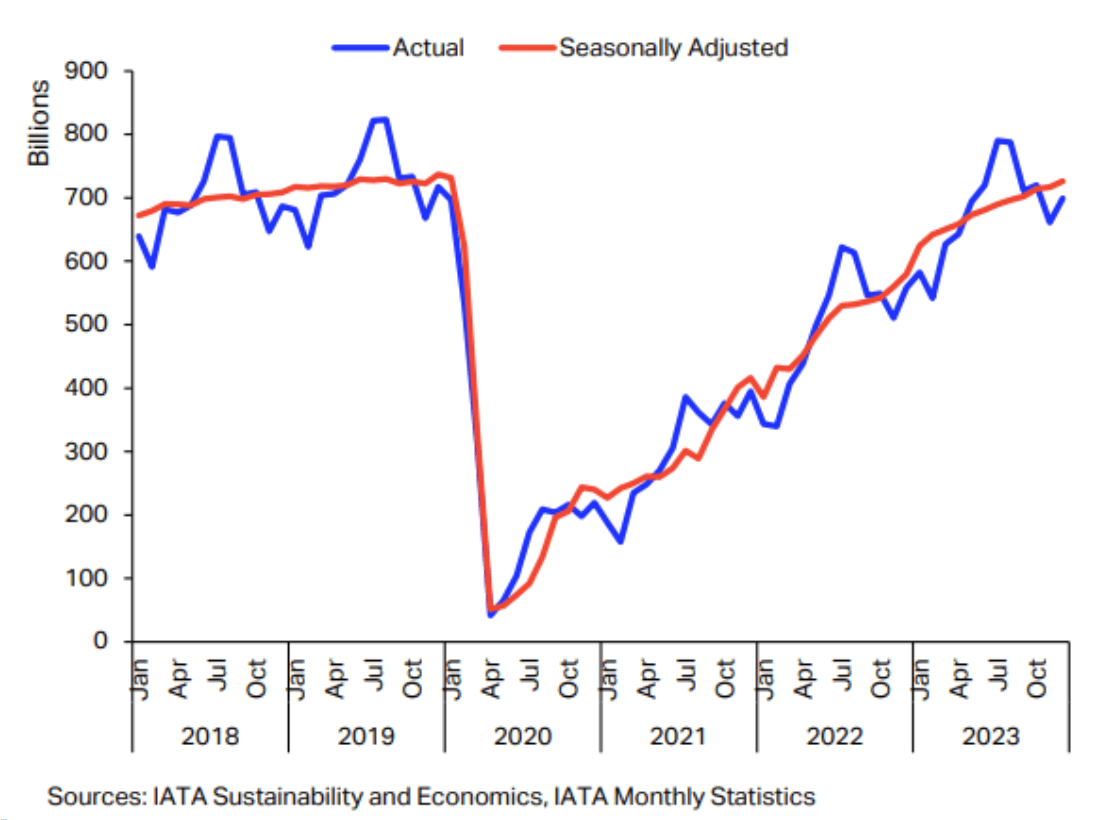

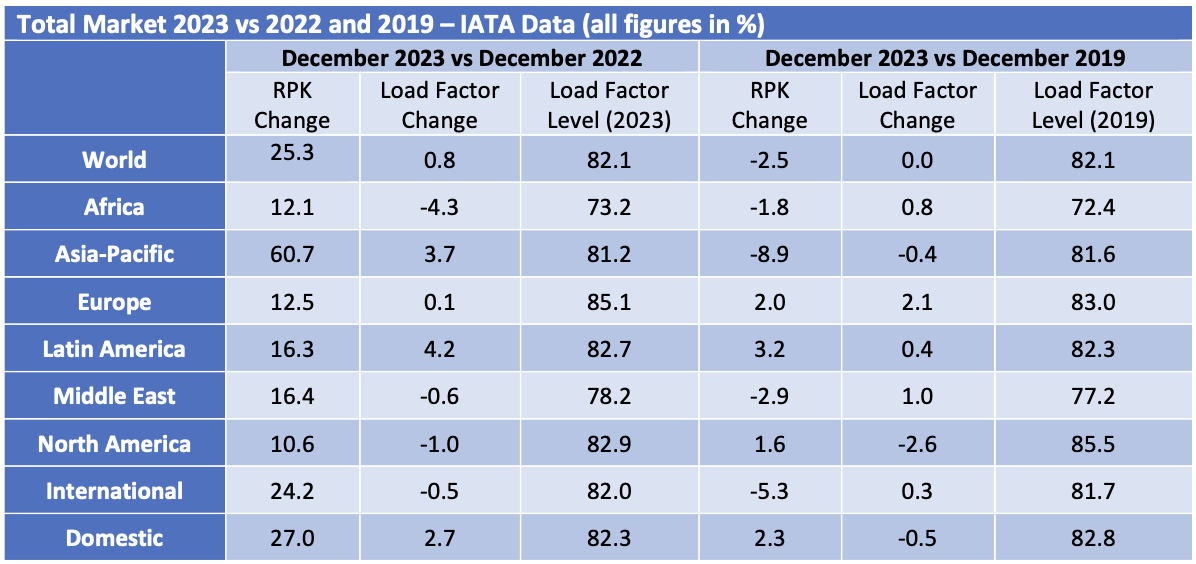

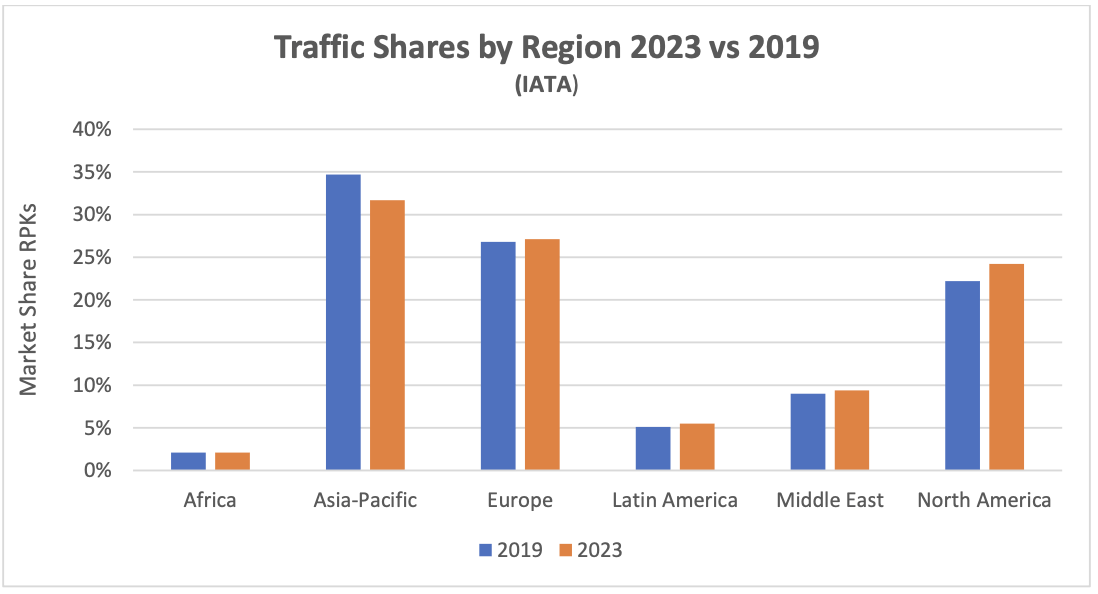

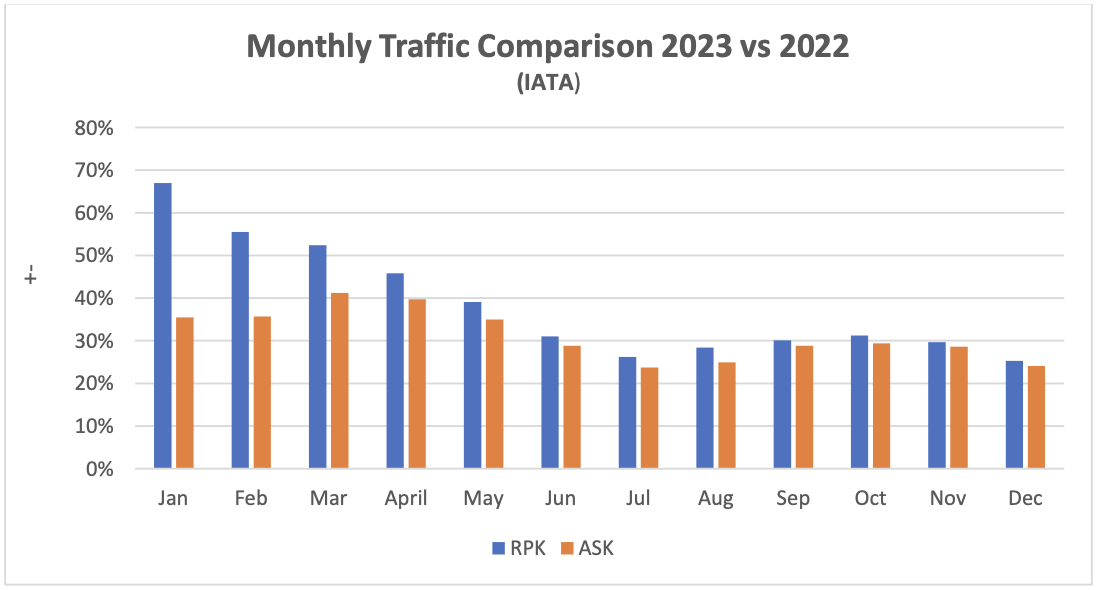

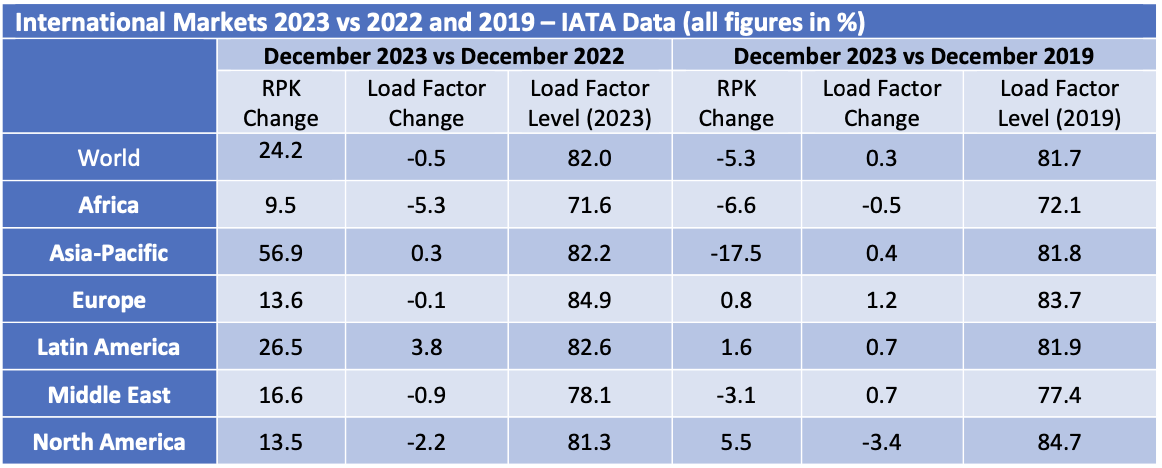

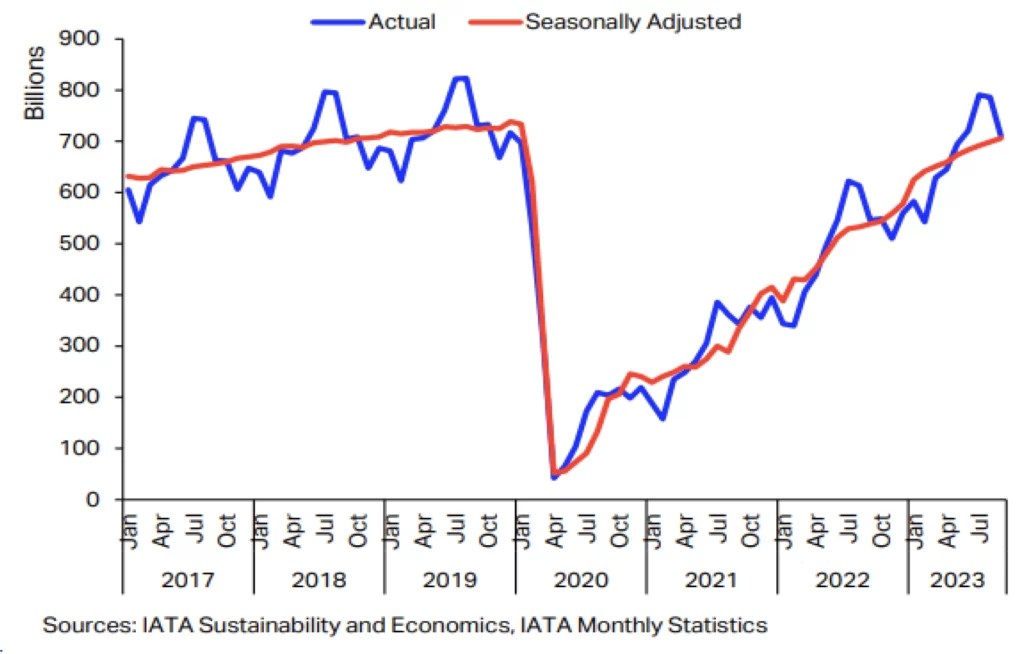

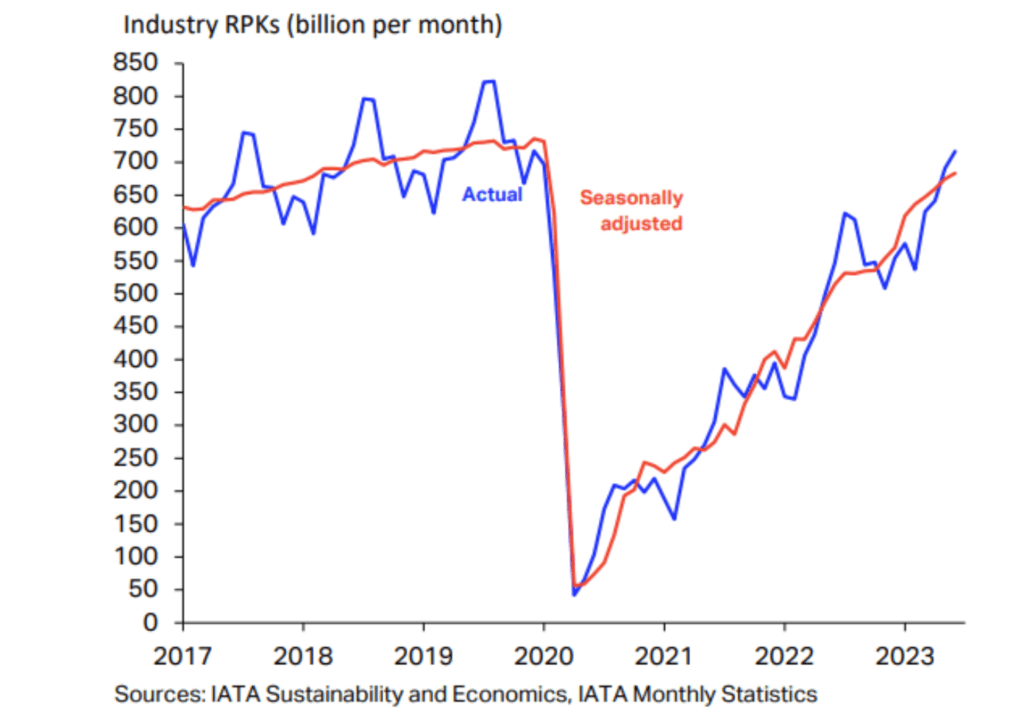

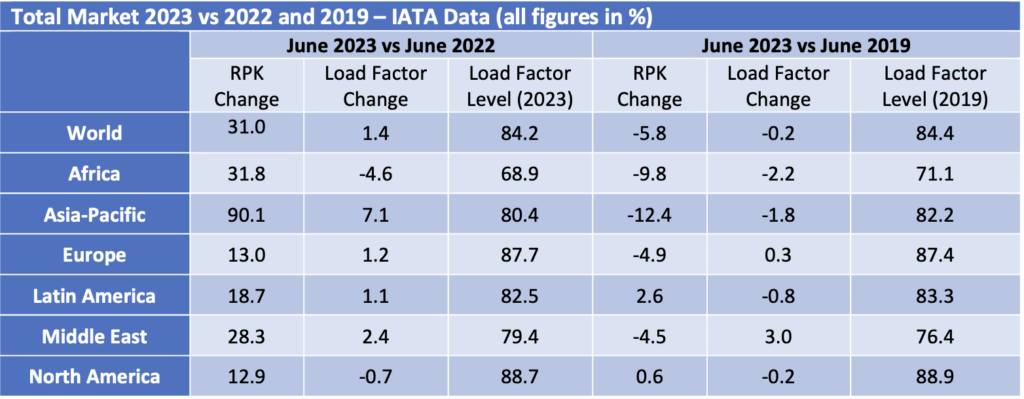

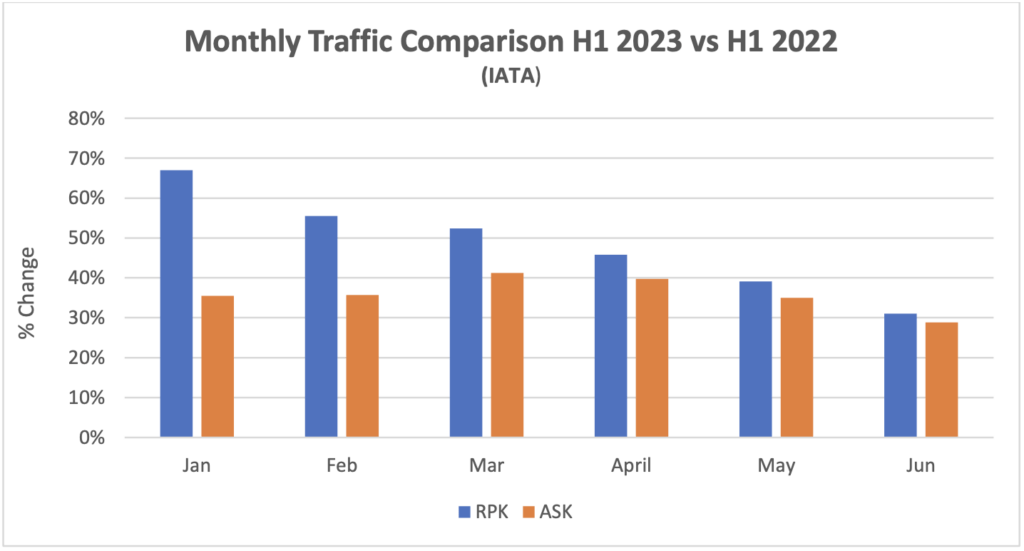

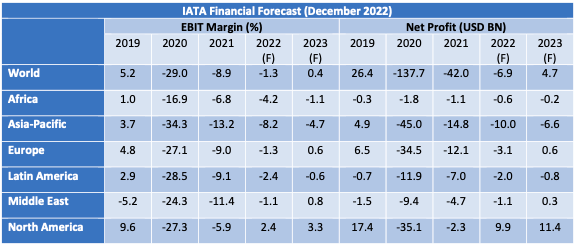

During 2024 RPKs [2] grew 10.4%, slightly faster than ASKs[3] leading to an improvement in load factor, and broadly in line with IATA’s full year forecast of 11.2%. 2024 also was the first year where total RPKs exceeded 2019. Growth by region was strongest in Asia-Pacific mainly because its recovery has been delayed compared to the rest of the world due to the relative persistence of pandemic-related government travel restrictions. International traffic growth was higher than domestic for the same underlying reasons.

The month of December 2024 was a bit weaker than expected (the IATA forecast referenced above was updated just weeks before the end of the year). However, growth improved significantly in January 2025, suggesting that December’s figures did not presage a persistent weakening trend.

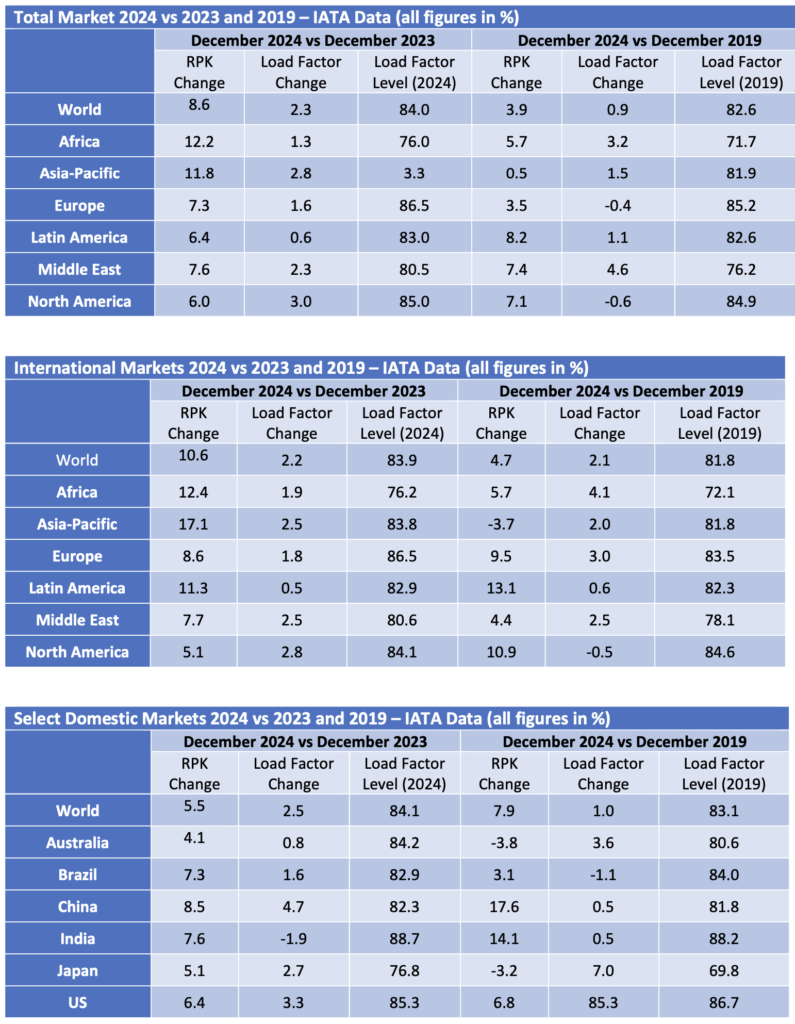

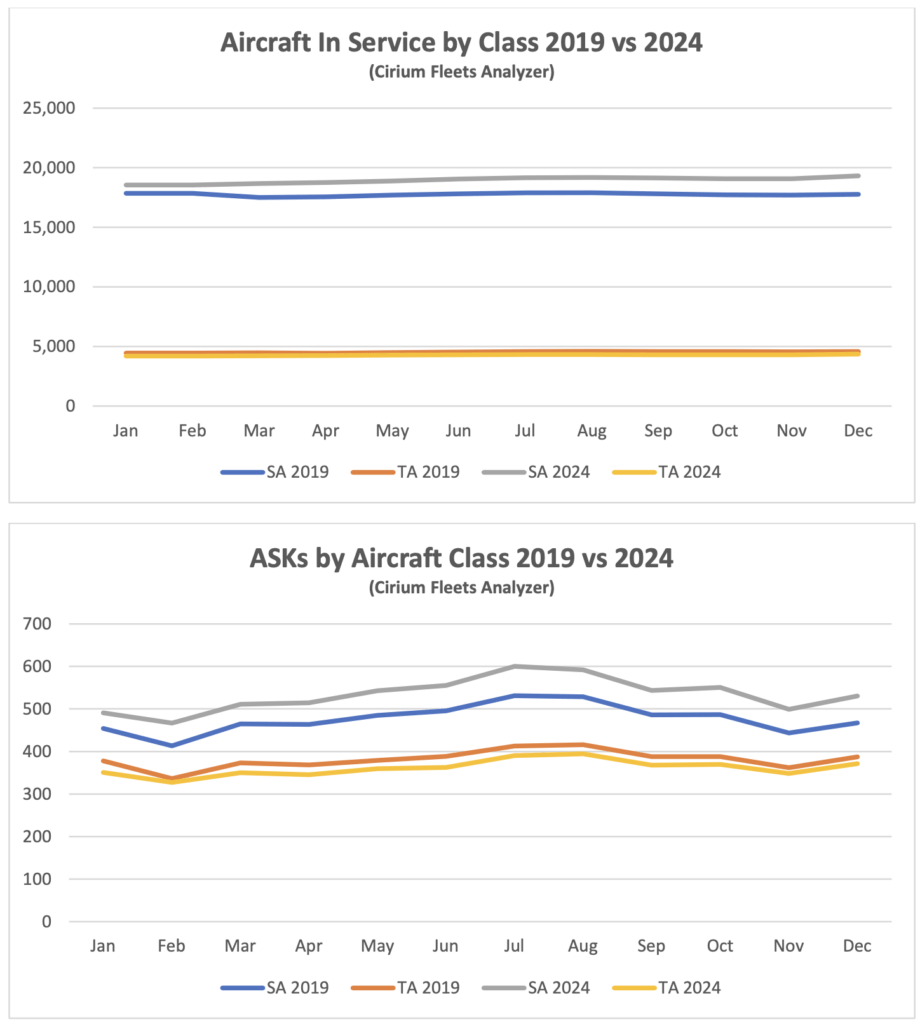

Although some short-haul aircraft serve international routes nearly all long-haul aircraft do so, and this is reflected in the relative demand for single-aisle (narrowbody) and twin-aisle (widebody) aircraft. Aircraft demand can be measured in terms of aircraft in service and ASKs, the standard measure of aircraft capacity deployed by airlines which indicates how intensively aircraft are being flown. Single aisle aircraft demand on both metrics is higher so far in 2024 than in 2019 whereas twin-aisle aircraft are marginally weaker by aircraft in service and lagging more in terms of ASKs. The difference between the two metrics may be down to the gradual move away from very large aircraft such as the B747 and A380 towards the smaller B787 and A350, resulting in fewer ASKs per aircraft unit. It is hard to see the TA 2024 data series because it is only very marginally lower than TA 2019.

Full recovery has yet to be achieved for twin-aisle aircraft, mainly due to weak traffic to and from, and within the Asia-Pacific region. The figures by region in the tables above are based on airline domicile, so weak Europe to Asia traffic reduces recorded international RPKs in other regions. Twin-aisle aircraft in service has shown a greater improvement relative to 2019 than ASKs which suggests that aircraft are being returned to service with lower utilisation in anticipation of continued recovery.

New Aircraft Supply

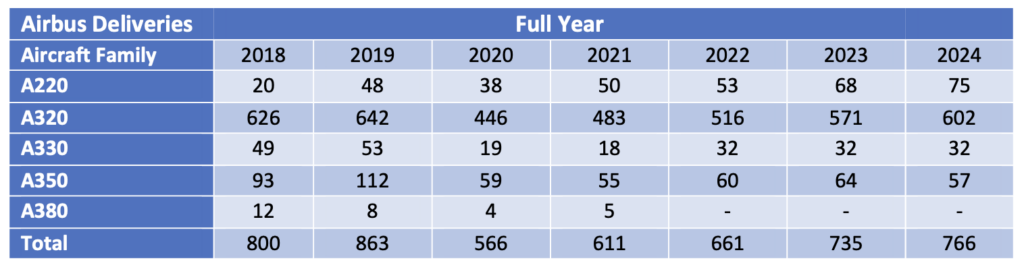

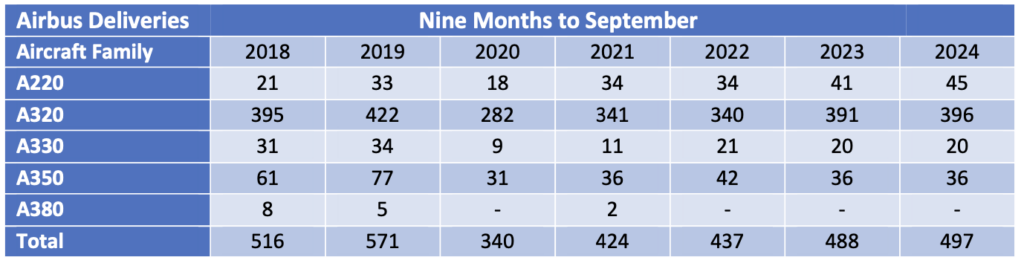

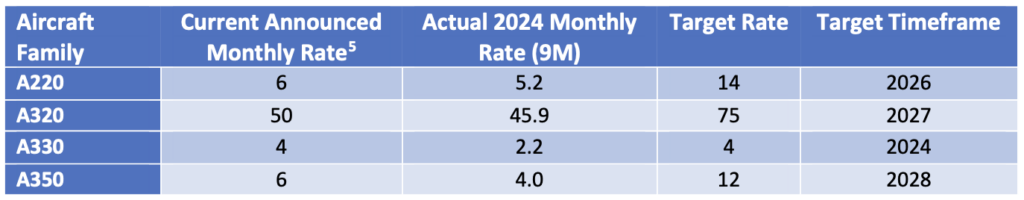

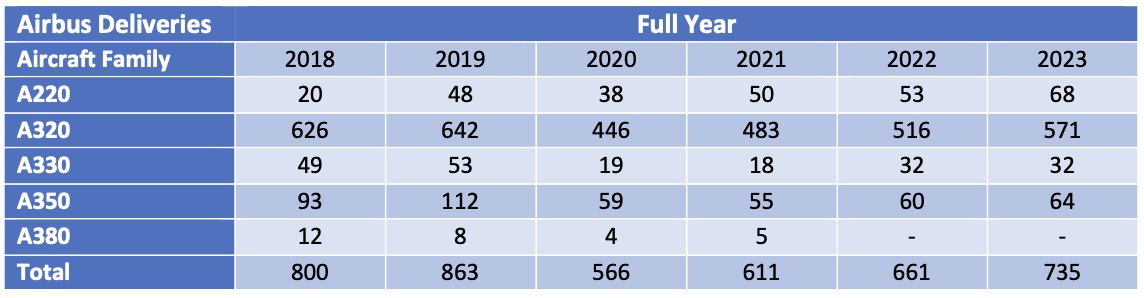

Airbus achieved 766 total deliveries in 2024, very close to its revised target of 770, and is guiding a 7% increase to 820 in 2025. The only change to medium-term production targets by model was a delay of the projected entry into service of the A350 freighter to the second half of 2027. The Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury singled out supply chain problems at Spirit Aerosystems as causing delays in production increases for the A200 and A350.

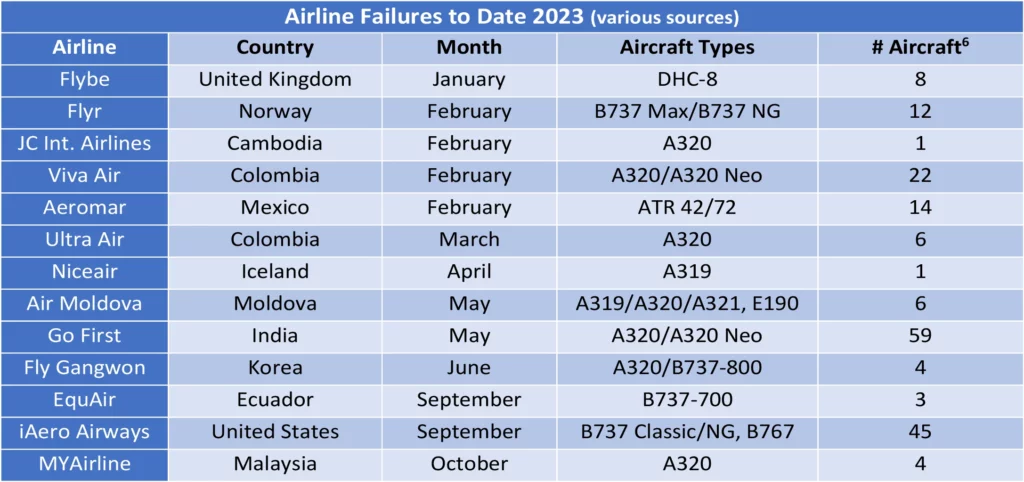

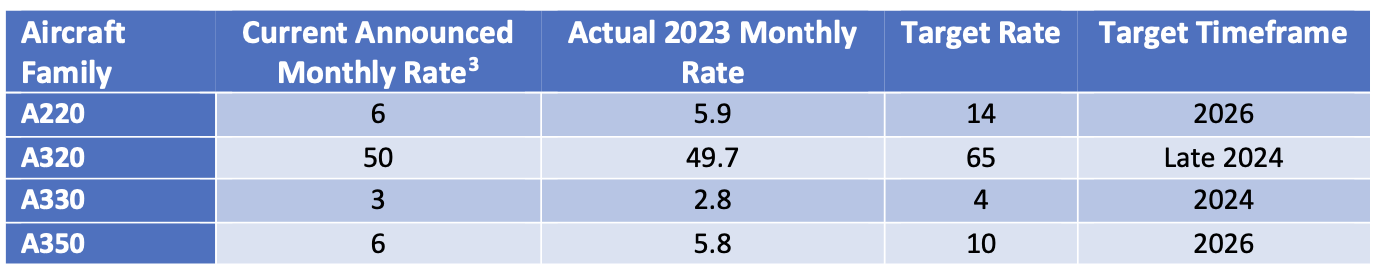

The status of Airbus’s production plans is:

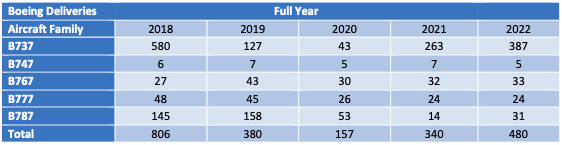

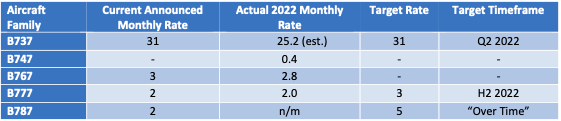

Boeing’s deliveries fell in 2024 because of the impact of a strike by members of the IAM and the FAA’s oversight of its production processes. Its inventory of B737s produced prior to 2023 fell from 175 to 55, implying that only 145 aircraft were built and delivered in 2024. The B787 inventory decreased from 50 to 25, implying that 26 aircraft were built and delivered in 2024. It is worth noting that these estimates assume that Boeing is using consistent definitions for inventory numbers which may not be accurate. Boeing plans to deliver all aircraft in inventory by the end of 2025.

Boeing has stopped providing official production guidance, so the monthly rates below come in shades of grey. Its long-term target for B737 production is 56 per month but this is clearly several years away. Fitch reports that B737 production is currently running at 20 per month, and the company plans to reach its maximum permitted rate of 38 by the middle of the year with a possible increase to 42 by year end subject to FAA approval. It plans to raise B787 production to 7 per month by the end of 2025 and to 10 by the end of 2026.

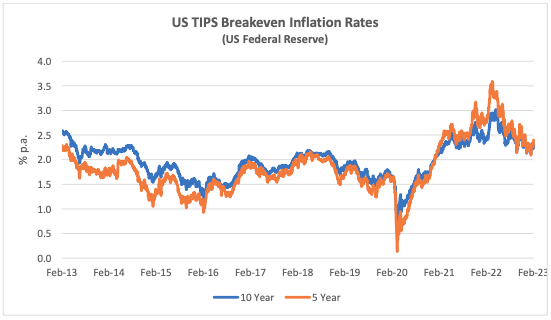

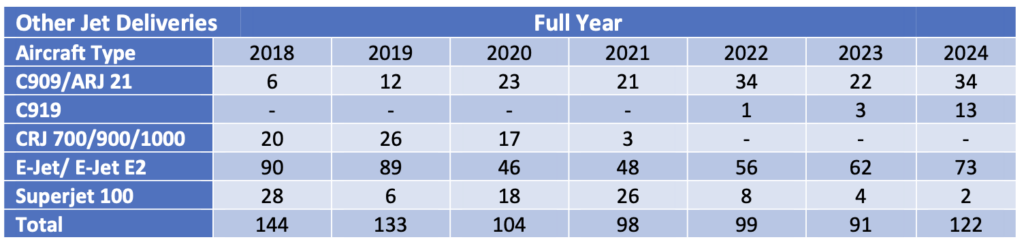

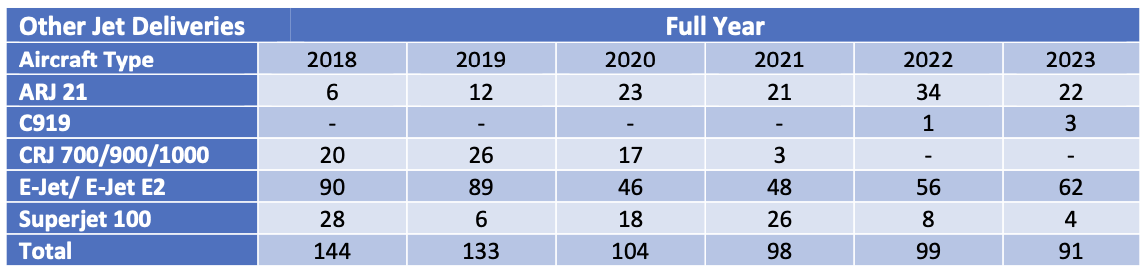

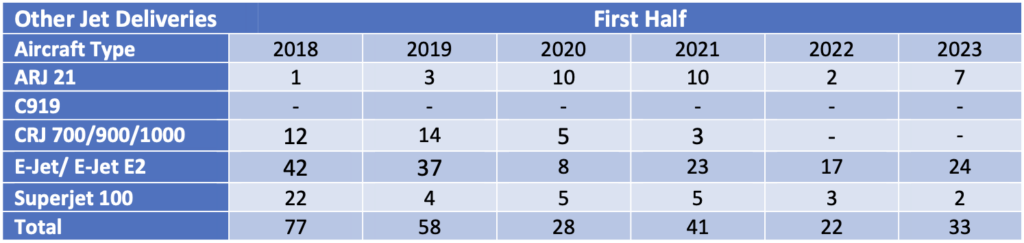

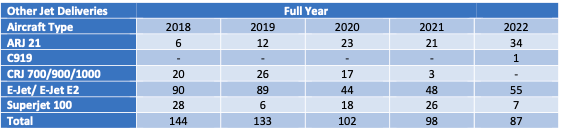

The number of commercial jets delivered by OEMs other than Airbus and Boeing showed a significant increase in 2024 which is likely to continue in 2025. Embraer increased commercial jet deliveries to 73 in 2024 and is guiding total deliveries between 77 and 85 in 2025. COMAC of China achieved a significant increase in C909 (a rebrand of the ARJ 21) and C919 deliveries to a combined 47 aircraft in 2024. Although there is no indication in any change of the current C909 production rate of 3 aircraft per month, company announcements indicate plans to deliver 30 C919s in 2025 and an increase in capacity to 50 aircraft a year.

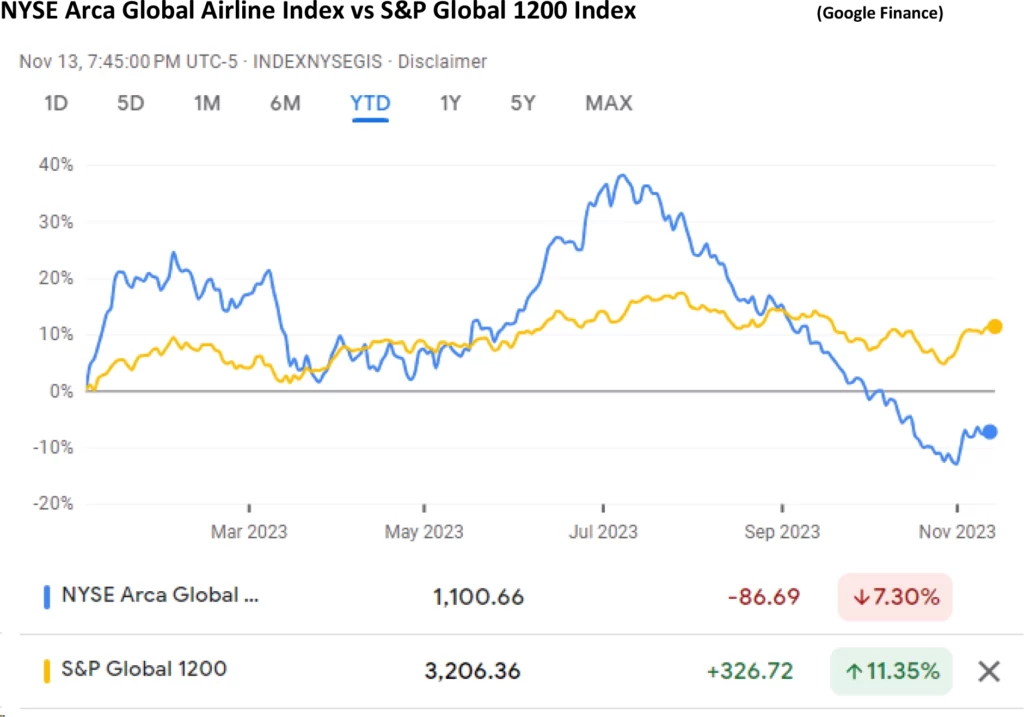

Airline Industry Financial Performance

Airline shares rallied very strongly from Q3 2024 to catch up with the overall market. This was mainly due to strong performance by the US network airlines (United in particular) on the back of strong premium travel demand and moderating fuel prices. Since January 2025 there has been a sell-off due to the impact of economic uncertainty on the revenue outlook for these operators.

Ironically enough November also saw the largest airline bankruptcy of 2024 when Spirit Airlines filed for Ch. 11. Along with other US low-cost airlines Spirit had suffered from a switch in US passenger demand towards international travel and more effective competition from the large network airlines. It has also had to deal with the need to ground a significant proportion of its fleet due to unscheduled maintenance on its Pratt & Whitney GTF engines. Spirit exited bankruptcy at the beginning of March 2025 having successfully restructured its shareholding structure and some of its bond obligations. It is a measure of the strength of the aircraft market that it did not seek any concessions from its lessors.

The other large airline failure in 2024 occurred when GOL of Brazil filed for US bankruptcy protection in January. This was not a major surprise as GOL’s major competitors Avianca and LATAM had already done so during the pandemic and GOL had engaged in significant financial restructuring in the same timeframe.

[1] The CFM56 is used by both the A320 Ceo and B737NG, whereas the V2500 is only used by the A320 Ceo.

[2] RPKs is the acronym for revenue passenger kilometres, which is the product of the number of paying passengers times distance flown.

[3] ASKs is the acronym for available seat kilometres, which is the product of the number of available seats flown times distance flown.

Disclaimer

This Presentation has been made to you solely for general information purposes and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for legal, tax, accounting, investment, or financial advice. This Presentation is not a sales material and does not constitute or form any part of any offer, invitation or recommendation to the recipient, its affiliates or any other person to underwrite, sell or purchase securities, assets or any other product, nor shall it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied upon, in any way in connection with any contract or transaction decision relating to any securities, assets or any other product. None of Sirius, its affiliates or shareholders shall have any responsibility or liability to the recipient, its affiliates, shareholders or any third party in relation to this Presentation or any other document or materials prepared by Sirius or its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers, or agents. Sirius and its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers, and agents have taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this Presentation is accurate. Neither Sirius nor any of its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisors, or agents has any obligation to update this Presentation. Under no circumstances should the delivery of this Presentation, irrespective of when it is made, create an implication that there has been no change in the affairs of the entities that are the subject of this Presentation. This Presentation may be updated and amended by a supplement and, where such supplement is prepared, this Presentation will be read and construed with such supplement. The statements herein which contain such terms as "may", "will", "should", "expect", "anticipate", "estimate", "intend", "continue" or "believe" or the negatives thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology are forward-looking statements and not historical facts. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the fairness, accuracy, or completeness of such statements, estimates and projections. The recipient should not place reliance on any forward-looking statements. Neither Sirius nor its affiliates undertake any obligation to update or revise the forward-looking statements contained in this Presentation to reflect events or circumstances occurring after the date of this Presentation or to reflect the occurrence of anticipated events. The information set out in this Presentation has been prepared by Sirius based upon various methodologies and calculations which it believes to be reasonable and appropriate. Past performance cannot be a guide to future performance. In preparing this Presentation, Sirius has relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources or which was provided to it or otherwise reviewed by it. This Presentation supersedes and replaces any other information provided by Sirius or its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers, or agents in respect of the content of the Presentation. No information or advice contained in this Presentation shall constitute advice to an existing or prospective investor in respect of his personal position. None of Sirius, its affiliates, or its affiliates’ officers, directors, employees or advisers, connected persons or any other person accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising, directly or indirectly, from this Presentation or its contents.

Industry Update Q3 2024

- Special Topic – Aircraft Leasing Industry Financial Performance

- Macro-Economic Background

- Traffic and Aircraft Demand

- New Aircraft Supply

- Airline Industry Financial Performance

Where are all the early retirements? Is it different this time?

Aircraft Leasing Industry Financial Performance

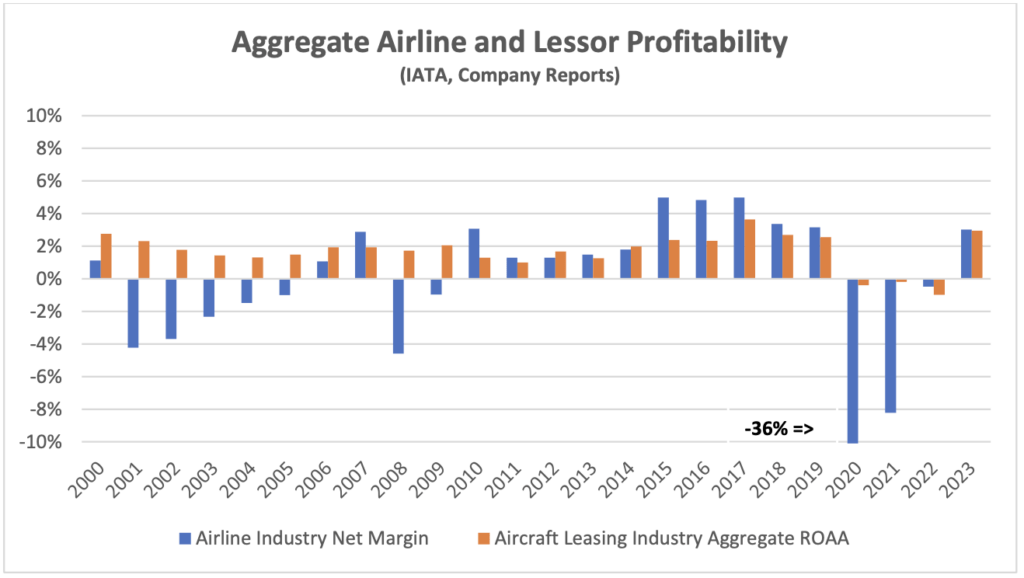

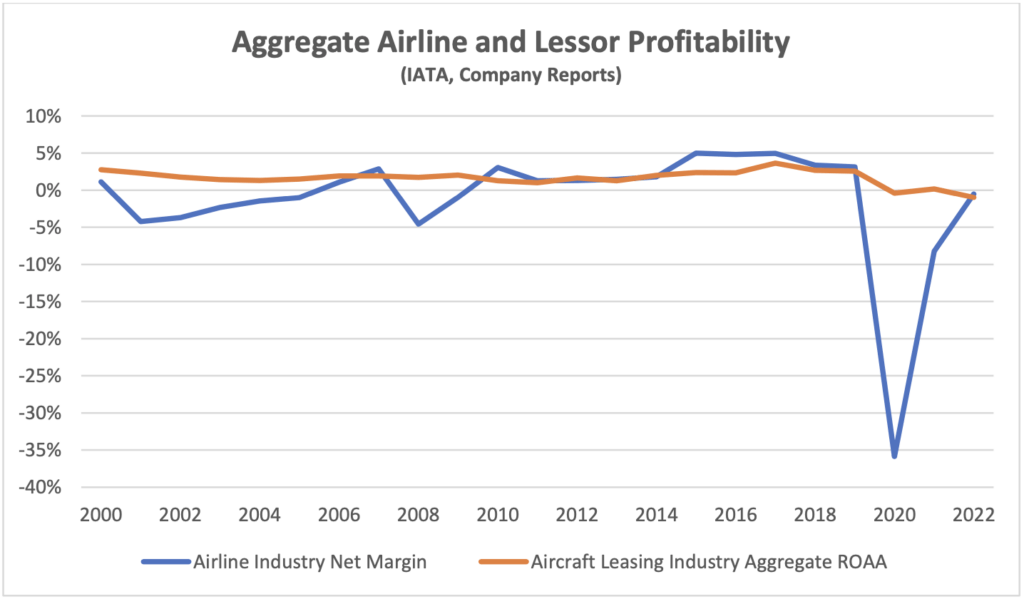

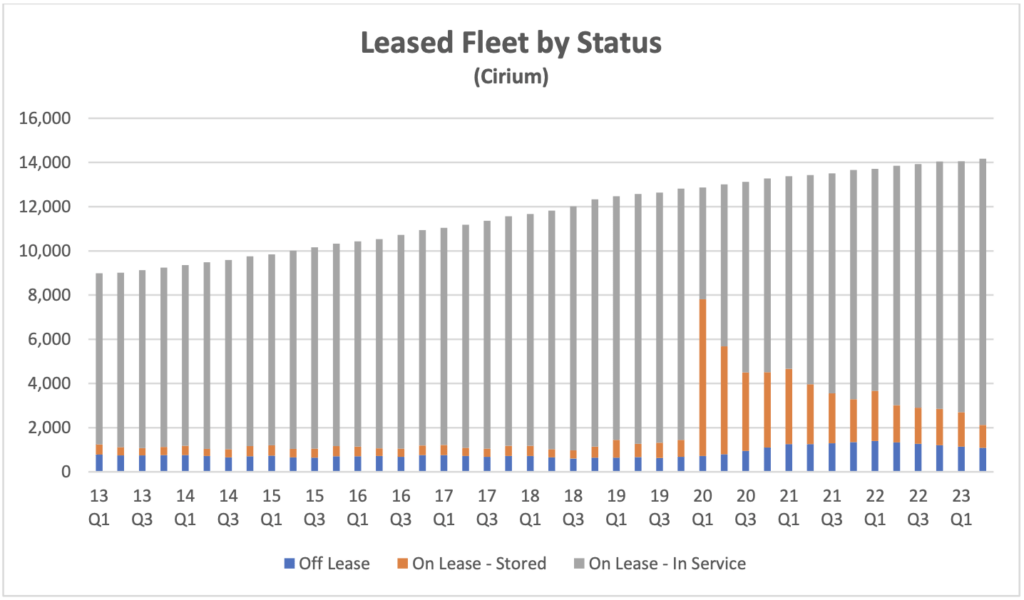

2023 saw a significant improvement in the profitability of the aircraft leasing industry. There were no major asset write-downs such as those incurred because of Covid, and the de facto expropriation of most aircraft leased to Russian airlines in 2022. In fact, several lessors were able to write back some of the latter charges as they received partial insurance settlements. Despite these unprecedented problems the aggregate performance of the industry has been relatively stable, particularly relative to the performance of the airline industry[1].

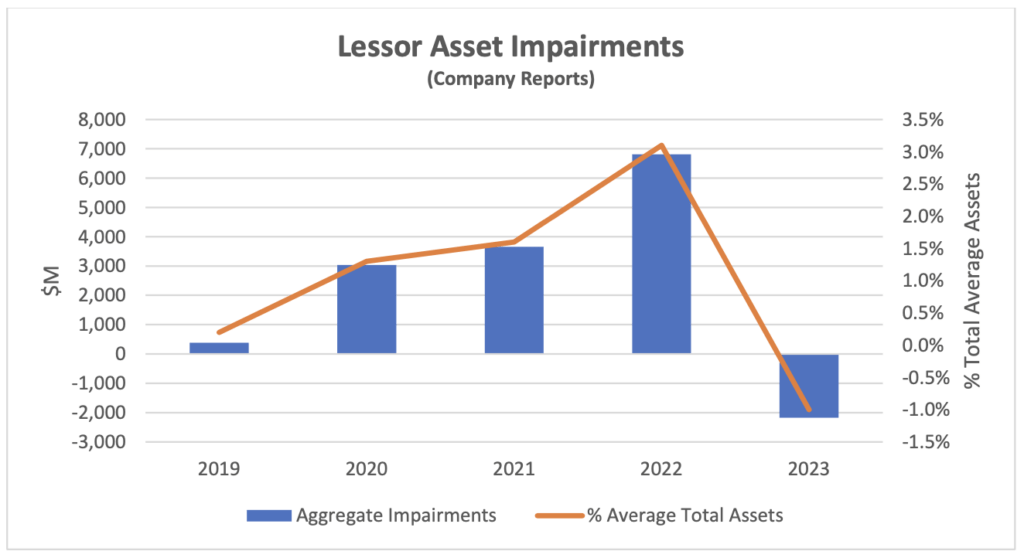

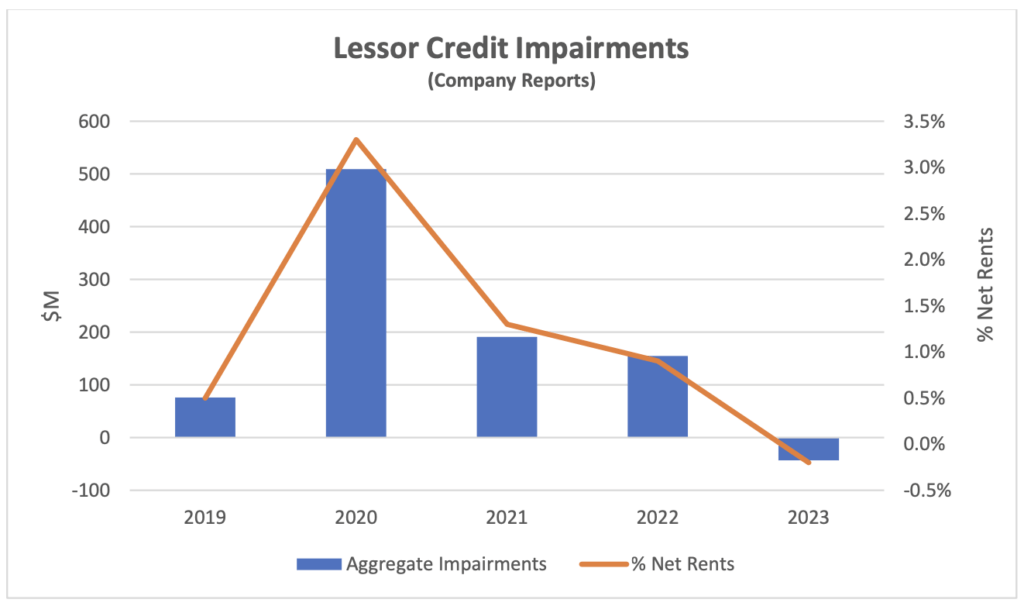

Asset impairments and write-backs have had a huge impact on aggregate industry results since 2020 as shown in the chart below. Insurance settlements in respect of aircraft expropriated by Russia are likely to have a positive impact on results in 2024 and beyond. Most amounts paid to lessors to date have been received from Russian insurers while litigation with western insurers continued. However, AerCap recently settled some of its claims with the latter which may presage more payments. It is a measure of the defensive financial strength of the industry that there has been very little financial distress in this period. Two lessors sought court protection, NAC and Voyager, which both had niche asset strategies based on regional and widebody aircraft respectively. None of the major lessors with more diverse aircraft fleets suffered a credit rating downgrade.

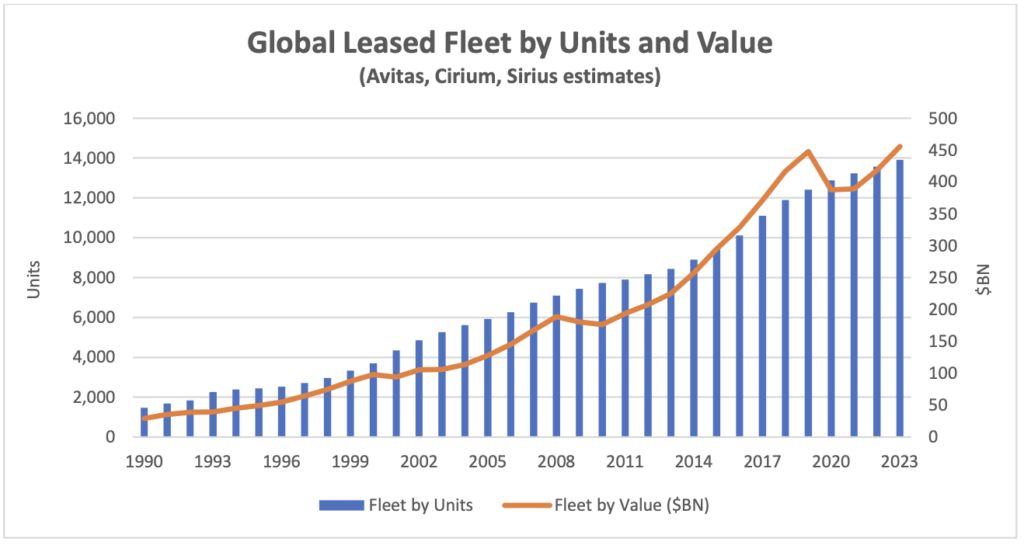

Before we discuss underlying financial performance it’s worth a detour to note some important changes to the industry background for aircraft lessors. First growth in terms of asset value has slowed down. This is mainly due to the disruption of new aircraft deliveries particularly at Boeing which is discussed in more detail below. There has also been some impact from cyclical changes in aircraft values although this has largely worked its way through the system (the chart below uses Avitas Market Values where available). This increases competition between lessors in the new aircraft market as most of them have targets for balance sheet growth although there are fewer deals available.

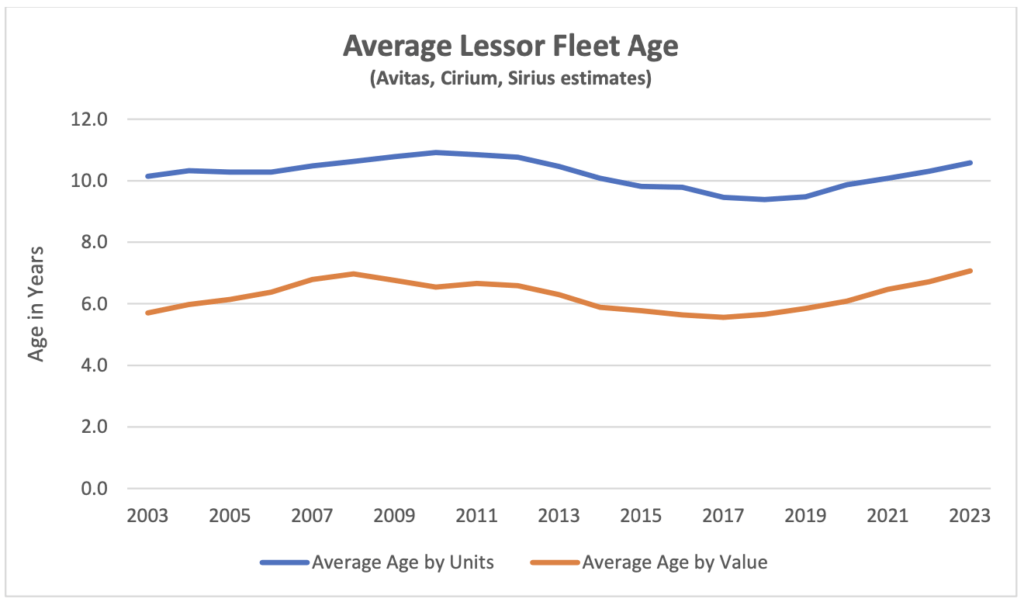

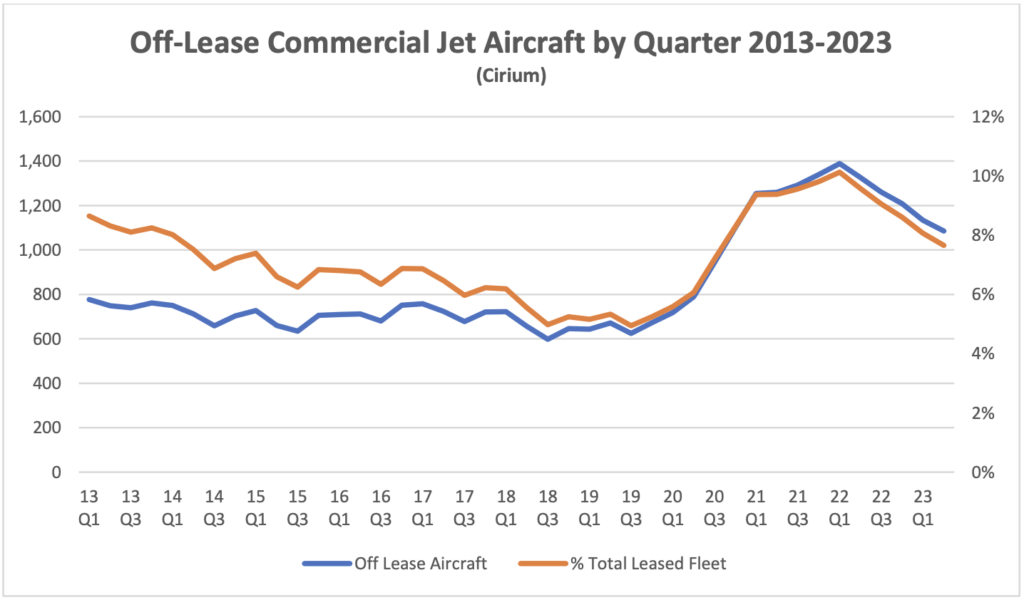

One side effect of the reduced level of new acquisitions is that the lessor fleet is ageing. This matters because an older fleet is likely to have higher levels of off-lease aircraft which may or may not be offset by higher rental income relative to aircraft book value. As the chart below shows age on a unit basis is consistently higher than on a value basis, which is the preferred age metric for analysing lessors. Average age by value is at its highest level in the last 20 years and is likely to increase further given the shortage of new aircraft deliveries.

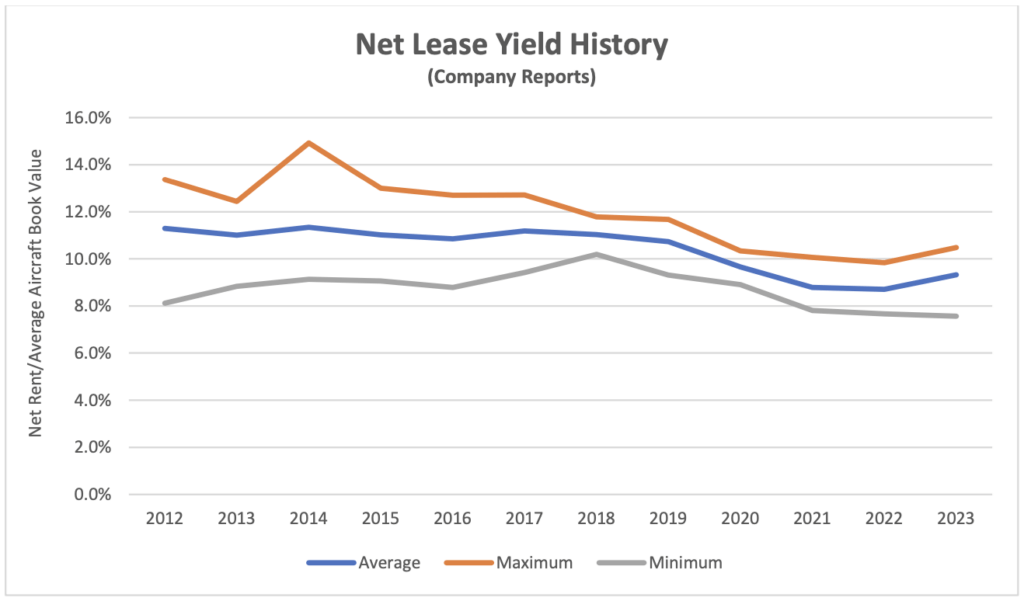

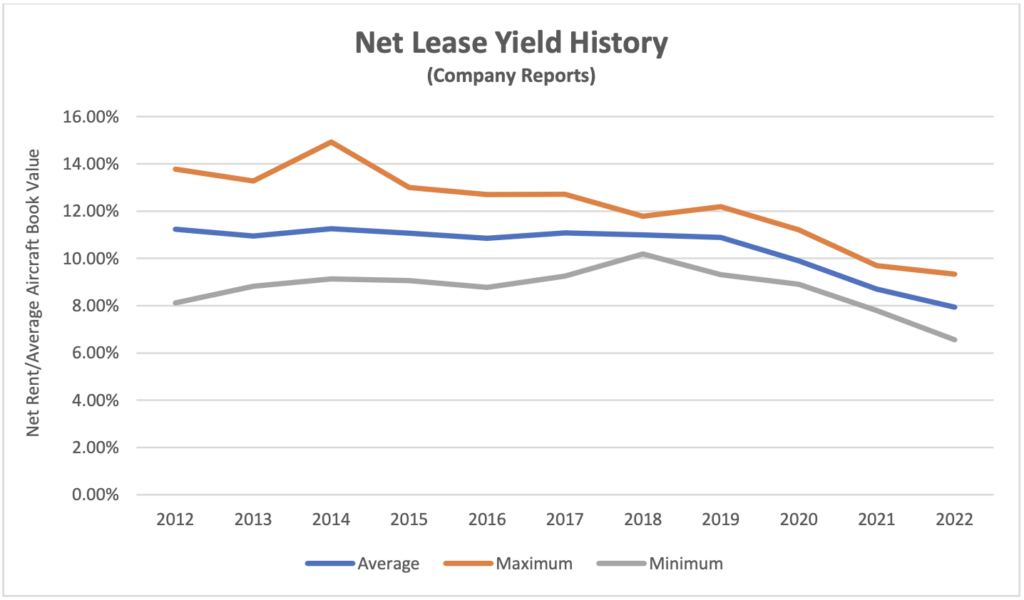

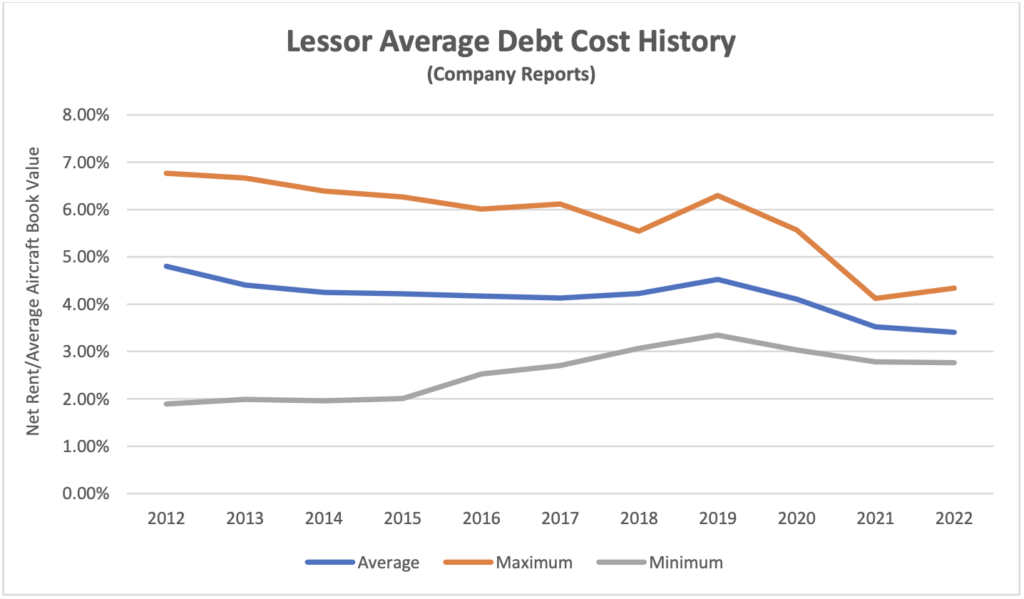

We believe net lease rental yield is a key measure of underlying performance. This ratio is the net rent earned by the lessor excluding maintenance rent etc. as a percentage of average aircraft book value and is analogous to rental yield in commercial property[2]. The chart below shows the range of yields achieved by the group of lessors we follow over the last ten years. This ratio has started to recover after a significant decline since 2019, but it is not a strong recovery as one would expect a higher yield if only because of fleet ageing.

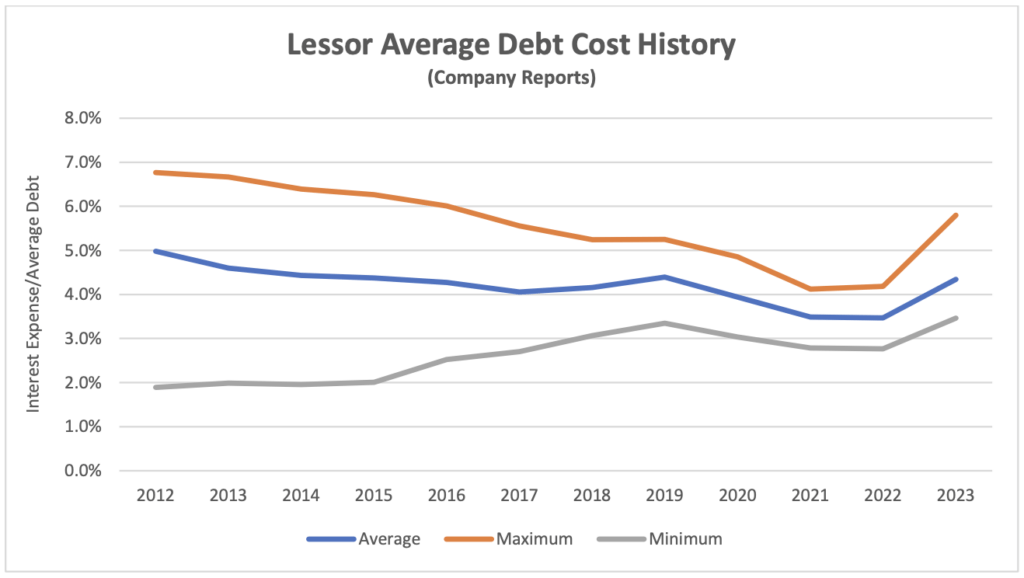

The recovery in yield also needs to be considered in the light of changes in interest costs. Interest expense is a key part of aircraft lessors’ cost of sales - they seek to pass on any increases to their airline customers in higher rents and are likely to pass on decreases by way of lower rents due to competitive pressures. One should not expect changes in interest rates to immediately feed through into aircraft lease rates as the relationship between them is more than a little “sticky” and tends to be hard to identify separately from the impact of changes in aircraft supply and demand. Lessors typically have significant medium-term fixed-rate borrowings to hedge their fixed-rate leases, so their cost of debt is relatively stable. Despite these caveats it would be reasonable to expect a greater increase in rents to have occurred in 2023 given the rise in interest rates and the increased age of the fleet.

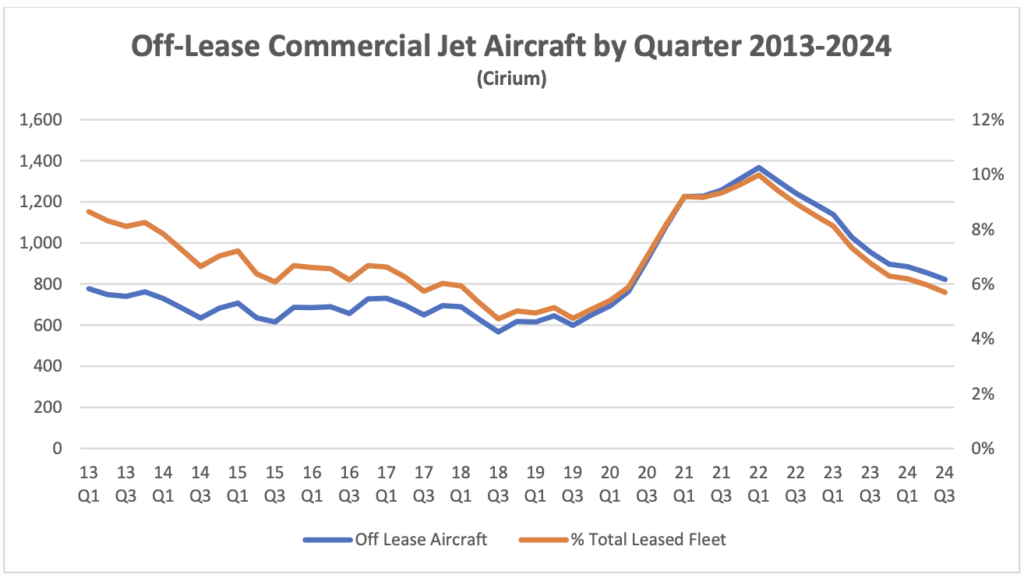

The reason for this muted recovery is unlikely to be high levels of off-lease aircraft as these have declined to relatively normal levels after taking into account fleet ageing since 2019. It should be borne in mind that aircraft out of service due to unscheduled engine maintenance remain on lease and accrue rent. It seems plausible that the slow recovery in rental yield is mainly caused by increased competition in the new aircraft market as lessors continue to pursue asset growth.

The level of credit impairments across the industry went negative in 2023, presumably due to reversals of provisions made in prior years. In most cases this is unlikely to be connected to Russian insurance settlements as most identifiable movements relating to these payments have been taken under the asset impairment heading, but there is plenty of scope for recoveries elsewhere.

Absent future major shocks we would expect these numbers to remain at low levels in future as was the case before 2020. There are several reasons why this is old and the new normal for the industry. The most important is that early lease termination is a common element of managing a delinquent lessee so rent no longer accrues and therefore does not have to be written off. Lessors are rightly very focussed on the integrity of their assets and associated records so physical possession is more important than “running the meter”, especially with a mobile asset that can be redeployed to earn revenue elsewhere.

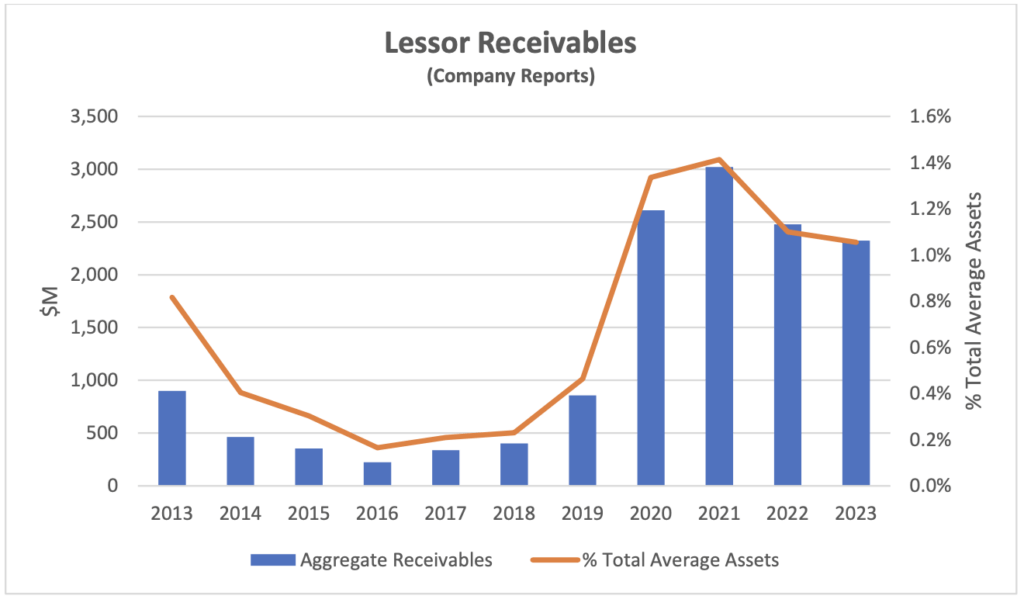

In contrast the level of receivables across the industry remains at a high level compared to 2019. We define receivables broadly and typically include items such as notes receivable as well as overdue rents as the latter often arise when rents are formally rescheduled. At a little over 1% of total assets this does not represent a major threat to the industry but is perhaps surprising given the recovery in airline profitability after 2021. The slow pace of decline is at least partly attributable to new airline restructurings as some lessors have seen an increase in this balance sheet item.

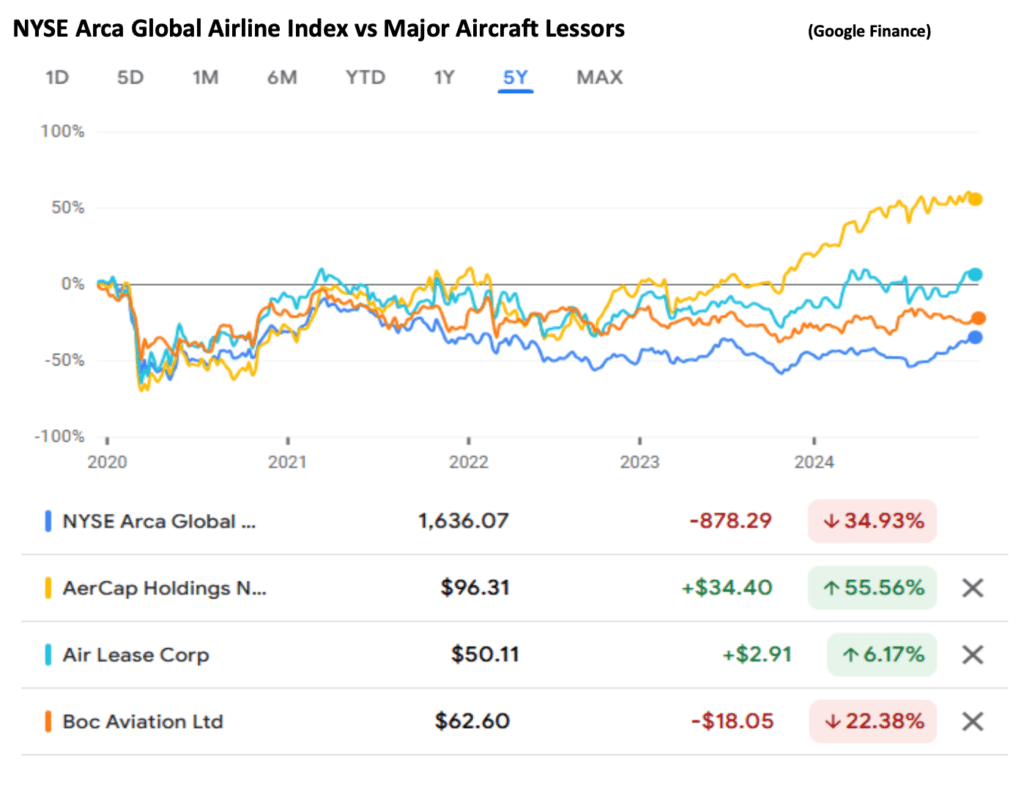

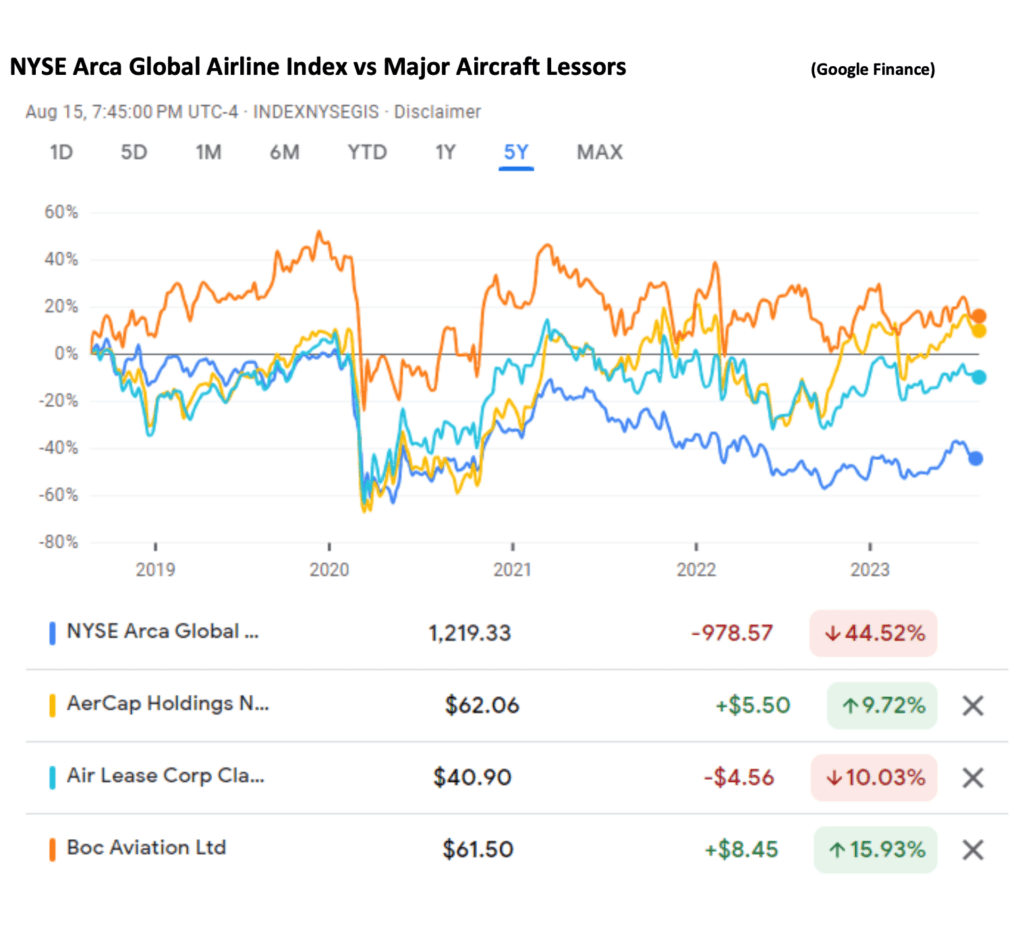

In the long run aircraft lessor stock prices have outperformed most airlines. The chart below compares the performance of the NYSE Arca Global Airline Index with the three largest public aircraft lessors over 5 years. The lessor stocks have significantly outperformed the airline industry during this period which encompasses both the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine.

Amongst the lessors the most notable development is the outperformance of AerCap. It would be easy to attribute this to the acquisition of GECAS, as AerCap’s earlier acquisition of ILFC saw its share price virtually double when the transaction was announced. However, the GECAS acquisition was announced in early 2021 and the outperformance only started in 2023. Another explanation that does not really make sense is business growth as AerCap’s balance sheet has shrunk since 2021 whereas Air Lease and BOC Aviation have both grown.

Where AerCap really differentiates itself from its comps is through its aggressive programme of share repurchases. From 2016 to 2023 AerCap spent nearly $6.5 billion buying back its own shares compared to its 2016 market capitalization of $7.3 billion (its current market capitalization is $18.8 billion). AerCap’s execution of this strategy has been driven by its ability to consistently sell aircraft at a profit, and it has benefitted shareholders as nearly all its share repurchases were at a discount to book value per share. Even now its share price to BV ratio is only a little over 1:1.

Macro-Economic Background

We have mentioned a few times recently that we want to shift the focus of our discussion of world GDP development from a look back to a look forward perspective. Looking back made a lot of sense in the last few years as this kind of data can be subject to major revisions and it was important to capture the overall impact of the pandemic from 2020 through 2024. Any revisions now are very small, so it is time to move on.

The chart below compares the IMF’s forecast for world GDP growth from its October 2024 World Economic Outlook with its three most recent predecessors. The forecast horizon moves forward each year, so it is helpful to create indices that help visualise the rate of change – obviously steeper is better. The 2024 forecast is notably more positive than the previous two years.

Economic growth is a key driver of long-term growth of air travel. However, since early 2022 its impact has been overshadowed by the fall and recovery in traffic associated with the pandemic. In time the influence of overall economic conditions on air travel is likely to reassert itself, but industry forecasts published by Airbus, Boeing and IATA assume much higher rates of traffic growth than GDP growth over the rest of the 2020s as the former catches up to its long-term trend (see our Q1 2024 Industry Update for a more detailed discussion).

The US Dollar has weakened since its recent peak in September 2022, providing relief for airlines outside the US for dollar-denominated costs such as fuel, aircraft rents and aircraft spares. The price of jet fuel has remained volatile, but it has moderated since February 2024. This reduction has mainly been driven by a reduction in the “crack spread” from c.$30 to c.$13.

Another indicator that is potentially important to aircraft investors is the breakeven inflation rate on US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). This indicator measures inflation expectations and it matters because used aircraft values are strongly influenced by the cost of new aircraft and over time this cost is linked to US Dollar inflation. In the short term this linkage is driven by escalation clauses in aircraft purchase contracts and in the long term by the general input cost environment for the aircraft manufacturers. The chart below compares the breakeven rate for 10-year and 5-year TIPS.

Although medium or long-term inflation expectations have never gone higher than 3.5%, actual inflation experience has been much higher in the last few years. This has led to higher appraised values for new aircraft.

Traffic and Aircraft Demand

Although some short-haul aircraft serve international routes nearly all long-haul aircraft do so, and this is reflected in the relative demand for single-aisle (narrowbody) and twin-aisle (widebody) aircraft. Aircraft demand can be measured in terms of aircraft in service and ASKs, the standard measure of aircraft capacity deployed by airlines which indicates how intensively aircraft are being flown. Single aisle aircraft demand on both metrics is higher so far in 2024 than in 2019 whereas twin-aisle aircraft are marginally weaker by aircraft in service and lagging more in terms of ASKs. The difference between the two metrics may be down to the gradual move away from very large aircraft such as the B747 and A380 towards the smaller B787 and nA350, resulting in fewer ASKs per aircraft unit. It is hard to see the TA 2024 data series because it is only very marginally lower than TA 2019.

Full recovery has yet to be achieved for twin-aisle aircraft, mainly due to weak traffic to and from, and within the Asia-Pacific region. The figures by region in the tables above are based on airline domicile, so weak Europe to Asia traffic reduces recorded international RPKs in other regions. Twin-aisle aircraft in service has shown a greater improvement relative to 2019 than ASKs which suggests that aircraft are being returned to service with lower utilisation in anticipation of continued recovery.

New Aircraft Supply

Airbus continues to guide total deliveries for 2024 at 770 commercial jets compared to 735 in 2023 although deliveries for the first nine months were only slightly higher at 497 vs 488. Chief executive Guillaume Faury stated during the 9 months Airbus results announcement that “We are struggling with more pragmatic issues as we speak now in 2024 for reaching the 770 (target)”. Single-aisle engines, cabin equipment and aerostructures are the main supply chain bottlenecks. On a more positive note, the first A321XLR delivered to Iberia at the end of October.

The latest announced status of Airbus’s production plans is:

Previously announced production plans included an interim target for A320 production of 65 per month but this was not mentioned as part of the most recent update. Although actual production rates to date are below current announced production rates Airbus normally delivers most aircraft in the fourth quarter, so they are likely to catch up by year end for most types.

Boeing suffered another disruption to its aircraft production activity when its machinists went on strike in September. There are reports that 737 Max production restarted in early December after the strike was resolved in November, although Boeing has not confirmed this. At the end of Q3 Boeing held an inventory of 60 B737-8 aircraft produced prior to 2023 compared to 175 at the start of the year, plus 35 -7 and -10 variants awaiting certification. B787 production has also been hit by the strike as well as supply chain problems and rework requirements. Inventory reduced from 50 at the start of the year to 30 at the end of Q3. The inventory reductions show that Boeing is struggling to deliver “new build” aircraft so far this year.

Boeing has stopped providing official production guidance. Its long-term target for B737 production is 56 per month but this is clearly several years away, and, in the meantime, production is capped at 38 a month by the FAA until it is happy that the manufacturer has resolved the quality control lapses that caused the door panel of an Alaska Airlines B737-9 to detach in flight last January. Several analysts have written that production will be at very low levels for some time. B787 production will also take time to build back towards Boeing’s target of 5 per month.

Boeing has also pushed back target entry into service dates for its new B777 models with B777-9 EIS now 2026, B777-8F 2028 and B777-8 2030.

The number of commercial jets delivered by OEMs other than Airbus and Boeing remains subdued. COMAC of China achieved a significant increase in ARJ 21 and C919 deliveries and slightly ahead of 2023.

Airline Industry Financial Performance

Airline shares have caught up with the broader stock market with a very strong Q4 so far. This is mainly due to strong performance by the US network airlines (United in particular) on the back of strong premium travel demand and moderating fuel prices.

Ironically enough November also saw the largest airline bankruptcy of 2024 when Spirit Airlines filed for Ch. 11. Along with other US low-cost airlines Spirit has suffered from a switch in US passenger demand towards international travel and more effective competition from the large network airlines. It has also had to deal with the need to ground a significant proportion of its fleet due to unscheduled maintenance on its Pratt & Whitney GTF engines. It reflects the strength of aircraft demand that Spirit management have said their bankruptcy restructuring objectives relate only to their obligations to shareholders and bondholders rather than lessors and other financiers.

The other large airline failure this year occurred when GOL of Brazil filed for US bankruptcy protection in January. This was not a major surprise as GOL’s major competitors Avianca and LATAM had already done so during the pandemic and GOL had engaged in significant financial restructuring in the same timeframe.

[1] Sirius has created the time series of aggregate aircraft leasing industry returns by based on public financial information in respect of the following companies: AerCap, Aircastle, Air Lease Corp., ALAFCO, Aviation Capital Group, Avolon, AWAS, BOC Aviation, CDB Aviation, DAE Capital, Fly Leasing, GECAS, Genesis Lease, ILFC, Intrepid/Voyager, Nordic Aviation Capital and SMBC Aviation Capital. We have excluded NAC from our calculations for 2022 because their net income includes a $2.6 BN gain on restructuring of financial liabilities and some other large one-off items.

[2] For the purposes of calculating net rental yield we include assets such as maintenance rights and lease premiums in aircraft book value as both these items are allocations of amounts paid for used aircraft and their exclusion would inflate net lease yield compared to aircraft bought new. We have excluded ALAFCO and NAC from these calculations

- ALAFCO has been subject to an orderly wind-down in recent years and this has made this ratio very volatile due to the timing of aircraft sales.

- NAC’s bankruptcy involved very substantial aircraft impairments relative to its total aircraft book value which have distorted this ratio.

[3] RPKs is the acronym for revenue passenger kilometres, which is the product of the number of paying passengers times distance flown.

[4] ASKs is the acronym for available seat kilometres, which is the product of the number of available seats flown times distance flown.

Disclaimer

This Presentation has been made to you solely for general information purposes and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for legal, tax, accounting, investment, or financial advice. This Presentation is not a sales material and does not constitute or form any part of any offer, invitation or recommendation to the recipient, its affiliates or any other person to underwrite, sell or purchase securities, assets or any other product, nor shall it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied upon, in any way in connection with any contract or transaction decision relating to any securities, assets or any other product. None of Sirius, its affiliates or shareholders shall have any responsibility or liability to the recipient, its affiliates, shareholders or any third party in relation to this Presentation or any other document or materials prepared by Sirius or its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers or agents. Sirius and its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers and agents have taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this Presentation is accurate. Neither Sirius nor any of its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisors or agents has any obligation to update this Presentation. Under no circumstances should the delivery of this Presentation, irrespective of when it is made, create an implication that there has been no change in the affairs of the entities that are the subject of this Presentation. This Presentation may be updated and amended by a supplement and, where such supplement is prepared, this Presentation will be read and construed with such supplement. The statements herein which contain such terms as "may", "will", "should", "expect", "anticipate", "estimate", "intend", "continue" or "believe" or the negatives thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology are forward-looking statements and not historical facts. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of such statements, estimates and projections. The recipient should not place reliance on any forward-looking statements. Neither Sirius nor its affiliates undertakes any obligation to update or revise the forward-looking statements contained in this Presentation to reflect events or circumstances occurring after the date of this Presentation or to reflect the occurrence of anticipated events. The information set out in this Presentation has been prepared by Sirius based upon various methodologies and calculations which it believes to be reasonable and appropriate. Past performance cannot be a guide to future performance. In preparing this Presentation, Sirius has relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources or which was provided to it or otherwise reviewed by it. This Presentation supersedes and replaces any other information provided by Sirius or its affiliates, officers, directors, employees, advisers or agents in respect of the content of the Presentation. No information or advice contained in this Presentation shall constitute advice to an existing or prospective investor in respect of his personal position. None of Sirius, its affiliates, its or its affiliates’ officers, directors, employees or advisers, connected persons or any other person accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising, directly or indirectly, from this Presentation or its contents.

Industry Update Q2 2024

- Special Topic – Aircraft Trading Update

- Macro-Economic Environment

- Traffic and Aircraft Demand

- New Aircraft Supply

- Airline Industry Financial Performance

Where are all the early retirements? Is it different this time?

Aircraft Trading Update

It is a cliché to point out that there is no “ticker” in the aircraft market. A result of this lack of transparency relative to some other asset types is the temptation to fall back on anecdotal evidence of market activity, which obviously runs the risk of confirmation bias, groupthink and other distortions.

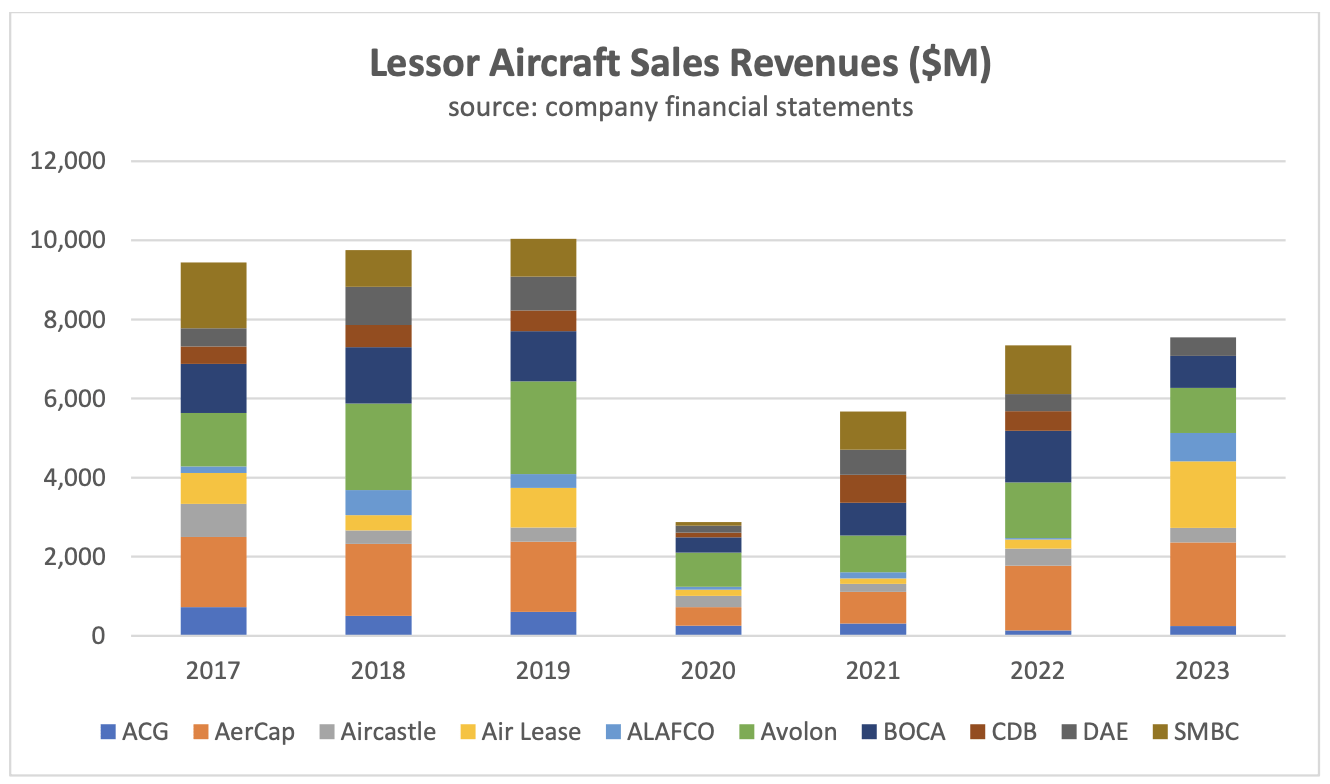

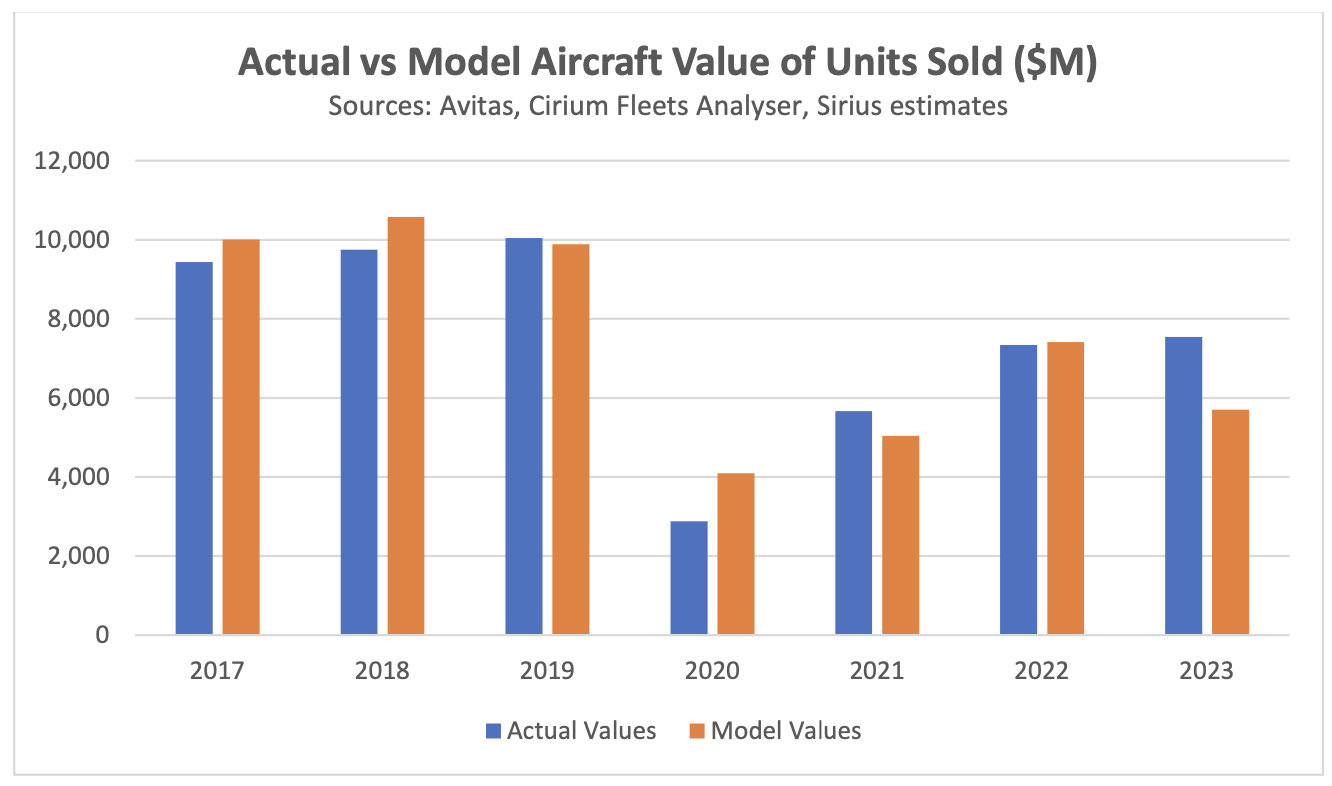

One source of real data is aircraft lessor financial statements which provides details of aircraft sales revenue and normally units sold as well. The chart below shows aircraft sales revenue for ten companies that could reasonably be classed as “new aircraft lessors”, which is to say that most of the aircraft they acquire are new or nearly new. The only significant exception is AerCap which has grown in part through the acquisition of competitors such as ILFC and GECAS, although these mature businesses were also built on the acquisition of new aircraft.

The chart shows the impact of the pandemic on trading activity. The sharp reduction aircraft sales revenues was driven by two key factors:

- A large proportion of the aircraft sold by these lessors are subject to lease and the sales process typically requires lessee (airline) co-operation. In 2020 and 2021 many airlines sought rent deferrals, and it would not have been practical for lessors to seek consent to an aircraft sale whilst simultaneously negotiating a rescheduling.

- Potential buyers of aircraft sought more attractive economics but there was little lessor appetite to sell at a loss, so the market largely failed to clear. None of the lessors featured in the chart suffered any material downgrade to their credit ratings because of the pandemic and they all had large liquidity buffers so they could afford to sit the market out.

The market has gradually recovered since 2020 although it has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. There is some understatement of activity in 2023 as CDB and SMBC have yet to publish their financials, but this is offset by GECAS trading activity being included as part of AerCap and a large one-off asset sale by ALAFCO.

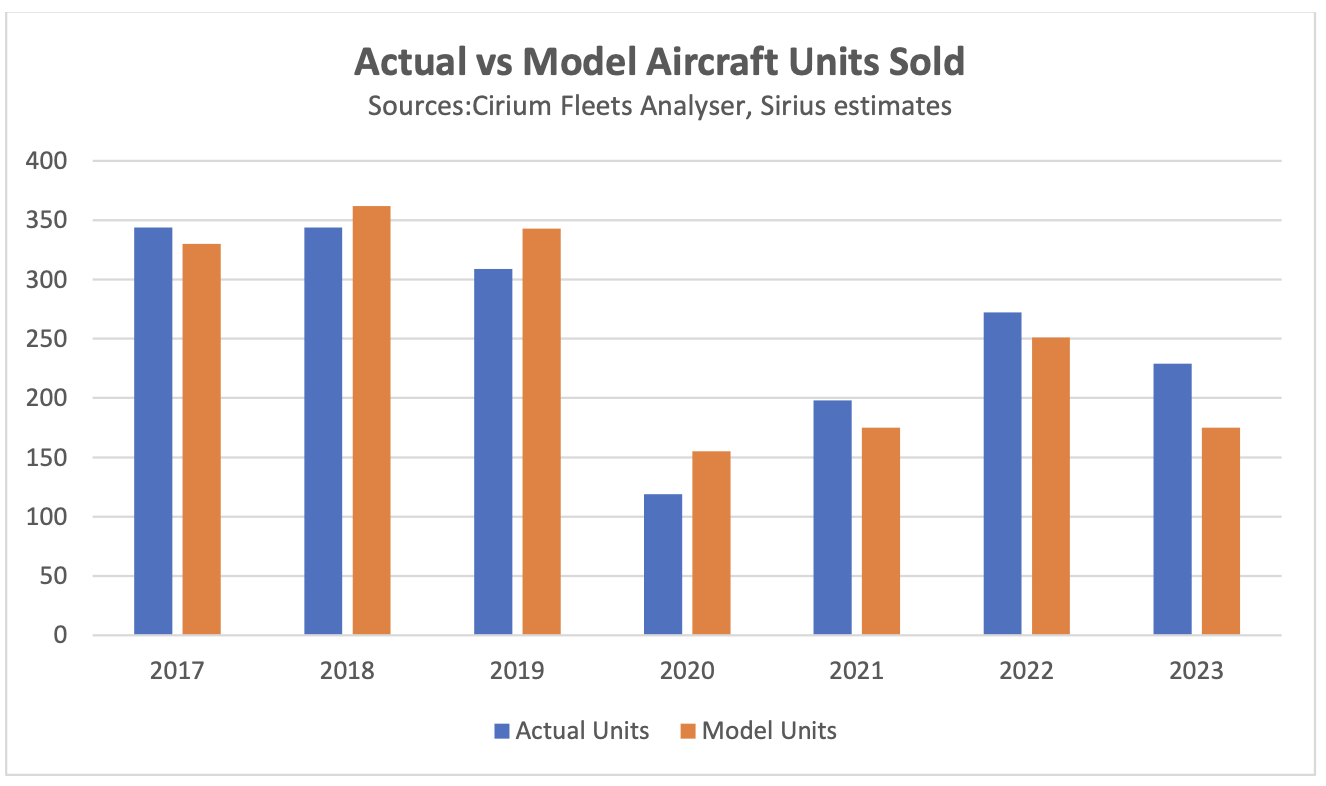

Given the limitations of this approach we thought it might be worth trying to use alternative data sources to get a better sense of the overall market. Our approach was to use data on the number of aircraft trades from Cirium Fleets Analyser combined with historical values from the Avitas Blue Book. There are a lot of reasons why this approach is not going to tie out too closely to the numbers from the financial statements, principally:

- It is challenging for data providers like Cirium to capture which aircraft are owned rather than managed by lessors as many aircraft are held in special-purpose companies which may or may not be owned by the lessor. We have assumed all aircraft managed by a lessor are also owned as we believe this is the “least bad” approach.

- The timing of a sale for accounting purposes may not coincide with the actual transfer of title and there may be delays in making the regulatory filings that allow data providers to identify a transaction.

- Avitas Blue Book values generally assume an aircraft is in a “half-life” maintenance condition whereas real world transactions reflect actual maintenance status and/or the impact of a lease in place.

The two charts below compare the “Actual” numbers in the financial statements with the numbers derived from our methodology which we refer to as the “Model” numbers. We have shown these numbers in the aggregate for all ten lessors and on this basis the two approaches tie out reasonably well, although there can be greater divergences at the level of the individual lessor. The relatively big shortfalls in the model vs actual figures by units and value in 2023 may reflect the impact of reporting delays as discussed above.

It seems reasonable to conclude that the Model approach is a reasonable basis for looking at the broader aircraft trading market although it’s probably best considered a guide to the direction of travel rather than an exact record.

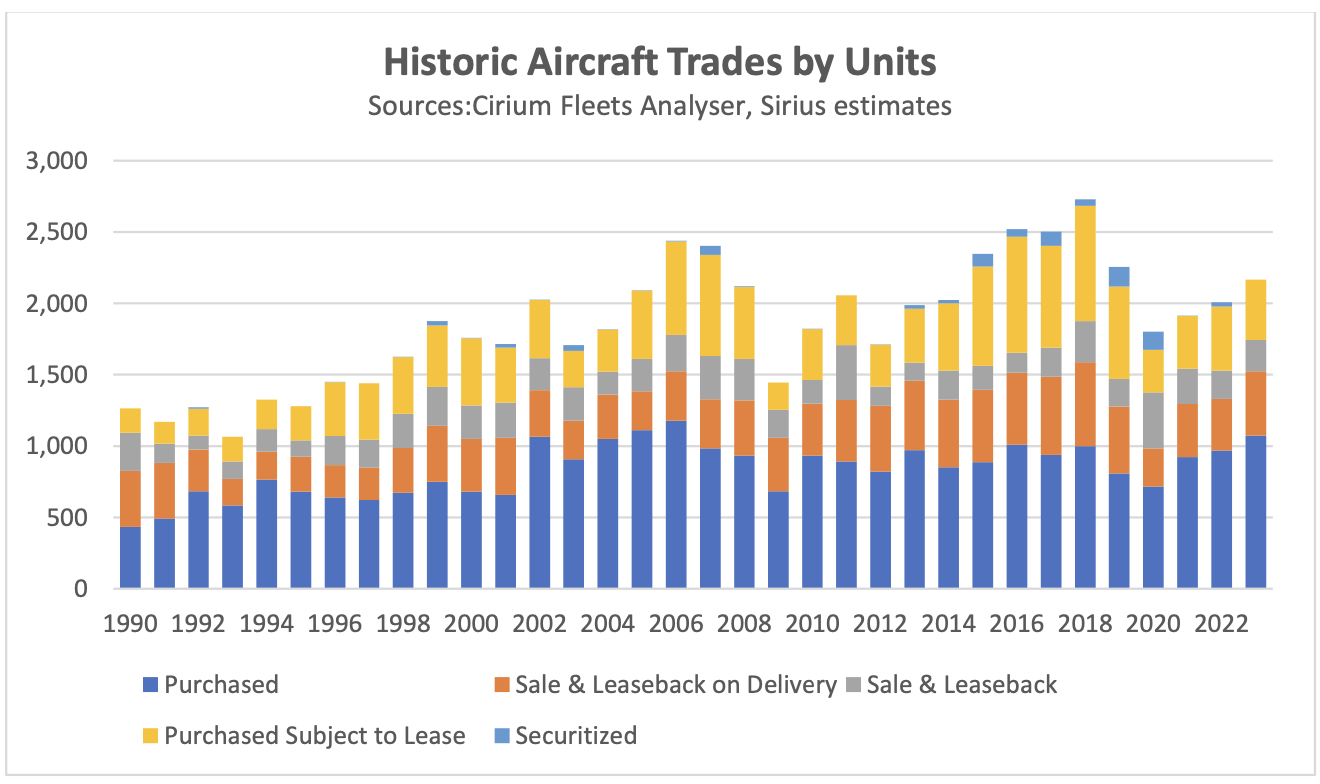

The kind of aircraft trading discussed above is a subset of the larger overall aircraft trading market. Cirium classifies aircraft purchases as:

- Purchase (no lease involved)

- Sale and leaseback on delivery

- Sale and leaseback

- Purchase subject to lease

- Securitization

Most of the sales by large lessors consist of aircraft subject to lease or securitizations. We have filtered the securitisation transactions to eliminate those which are financings rather than transfers of economic ownership. This is mainly a function of whether E notes were issued along with senior debt, but we have also researched industry publications and pre-sale reports. We have also eliminated some non-commercial aircraft types and there are some gaps in the value data available, but we still capture c. 90% of transactions overall and our coverage improves to more than 90% over time.

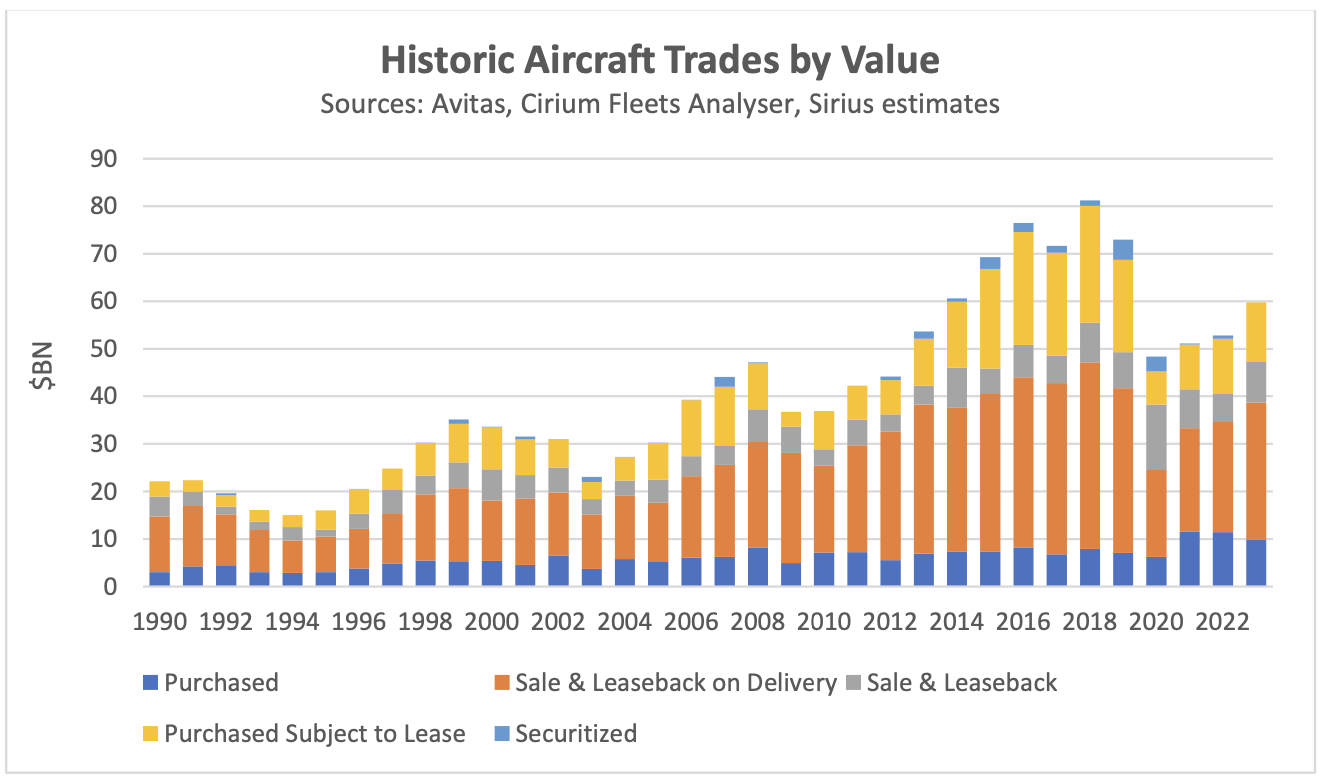

The charts below show historic aircraft trades from 1990 by category, units and value.

There is a striking difference between market shares for some transaction types based on value and units. Sale and leasebacks on delivery have very high unit values as they involve brand new aircraft and purchases with no lease attached tend to involve older aircraft with correspondingly low values. The other transaction types have relatively similar market shares by both units and value as they generally involve mid-life aircraft.

The transaction participants are mostly the kinds of companies one would expect. Most sellers in all sale-leasebacks are airlines and the buyers are financiers, principally operating lessors. Most sellers and buyers of aircraft subject to lease are operating lessors and in securitizations the sellers are typically operating lessors and the buyers special purpose companies.

Purchases with no lease attached are more varied. Airlines account for between 40% and 45% of sellers by units and value but only c. 30% of buyers. Financiers including lessors account for 50% to 60% of sellers and buyers by both units and value, and the lower airline share of purchases is made up of a mixture of non-airline aircraft operators (air taxi, military etc.) and MROs.

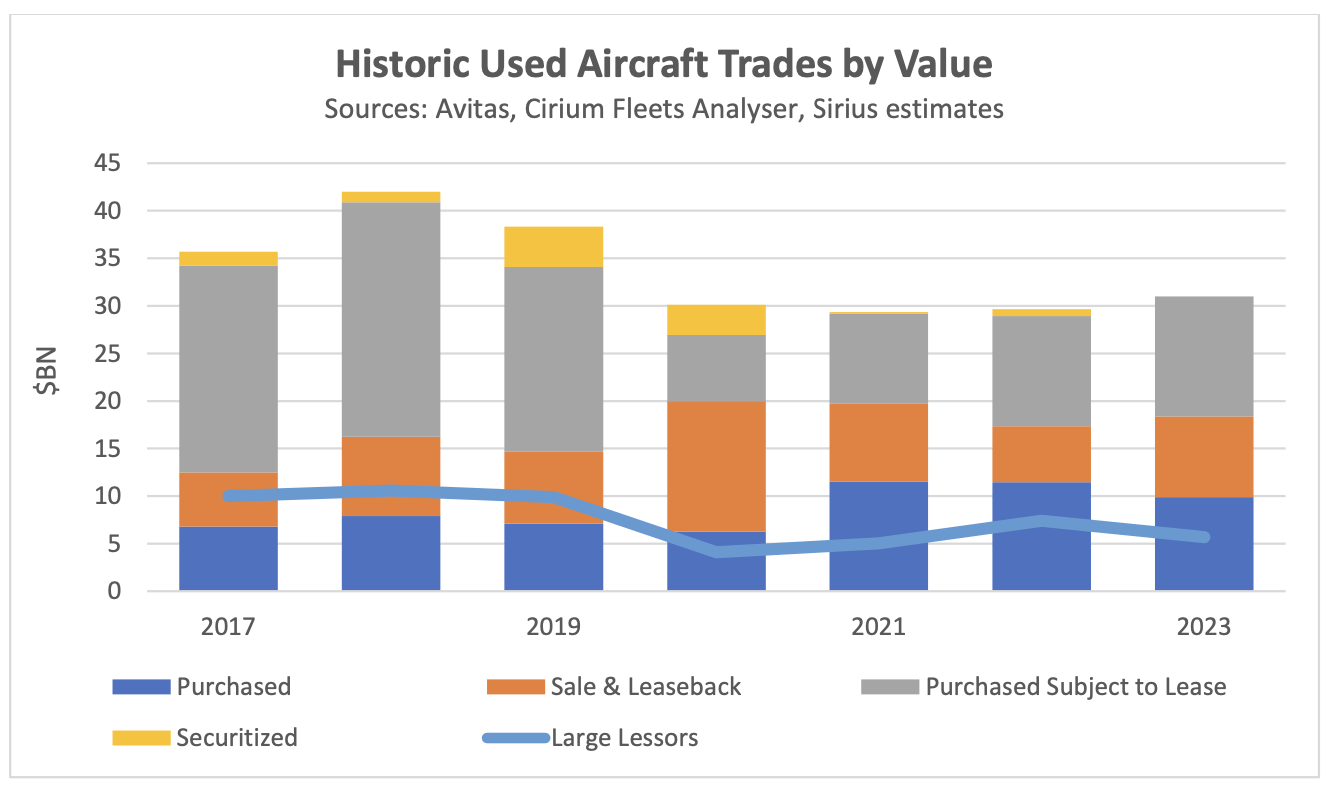

A key conclusion from this analysis is that the market for used aircraft trades is much larger than implied by an analysis based only on the financial statements of major lessors. Our final chart compares the overall market by value with this sub-set. This is true even if one excludes purchases without a lease and sale-leasebacks of used aircraft which are not a significant part of the large lessors’ sales offering.

It is also clear that the cyclicality in the trading activity of large lessors is also present in the overall market, although the reasons for lower trading activity in downturns may not be the same for other market participants.

Macro-Economic Environment

As we discussed in our Q1 2024 industry update we have changed our GDP focus from the retrospective amount of damage done by the pandemic to looking forwards. The IMF has gradually been taking a more optimistic view with its latest 2024 projection at 2.7% vs 2.4% only nine months ago.

Economic growth is a key driver of long-term growth of air travel. However, since early 2022 its impact has been overshadowed by the fall and recovery in traffic associated with the pandemic. In time the influence of overall economic conditions on air travel is likely to reassert itself, but industry forecasts published by Airbus, Boeing and IATA assume much higher rates of traffic growth than GDP growth over the rest of the 2020s as the former catches up to its long-term trend (see our Q1 2024 Industry Update for a more detailed discussion).

The US Dollar has weakened since its recent peak in September 2022, providing relief for airlines outside the US for dollar-denominated costs such as fuel, aircraft rents and aircraft spares. The price of jet fuel has remained volatile, but it has moderated since February 2024. This reduction has mainly been driven by a reduction in the “crack spread” from c.$30 to c.$12.

Another indicator that is potentially important to aircraft investors is the breakeven inflation rate on US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). This indicator measures inflation expectations and it matters because used aircraft values are strongly influenced by the cost of new aircraft and over time this cost is linked to US Dollar inflation. In the short term this linkage is driven by escalation clauses in aircraft purchase contracts and in the long term by the general input cost environment for the aircraft manufacturers. The chart below compares the breakeven rate for 10-year and 5-year TIPS.

Although medium or long-term inflation expectations have never gone higher than 3.5%, actual inflation experience has been much higher in the last few years. This has led to higher appraised values for new aircraft.

Traffic and Aircraft Demand

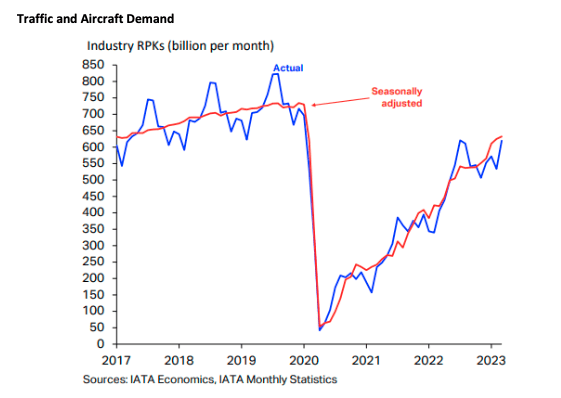

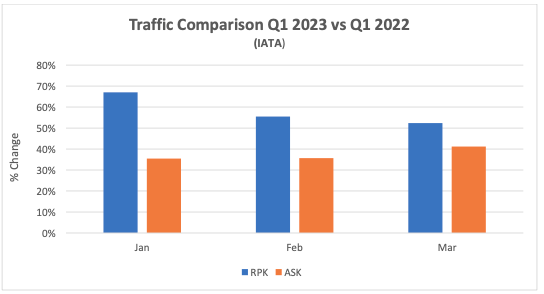

The IATA chart reproduced above looks like those included in previous industry updates but is in fact quite different. Previously it included actual and seasonally adjusted RPKs and now it has both seasonally adjusted RPKs[1] and ASKs[2] indexed to January 2020. For those of us who are not very interested in seasonal adjustments this new version has the benefit of capturing changes in load factors over time and shows that the load factor recovery was complete by the end of 2022.

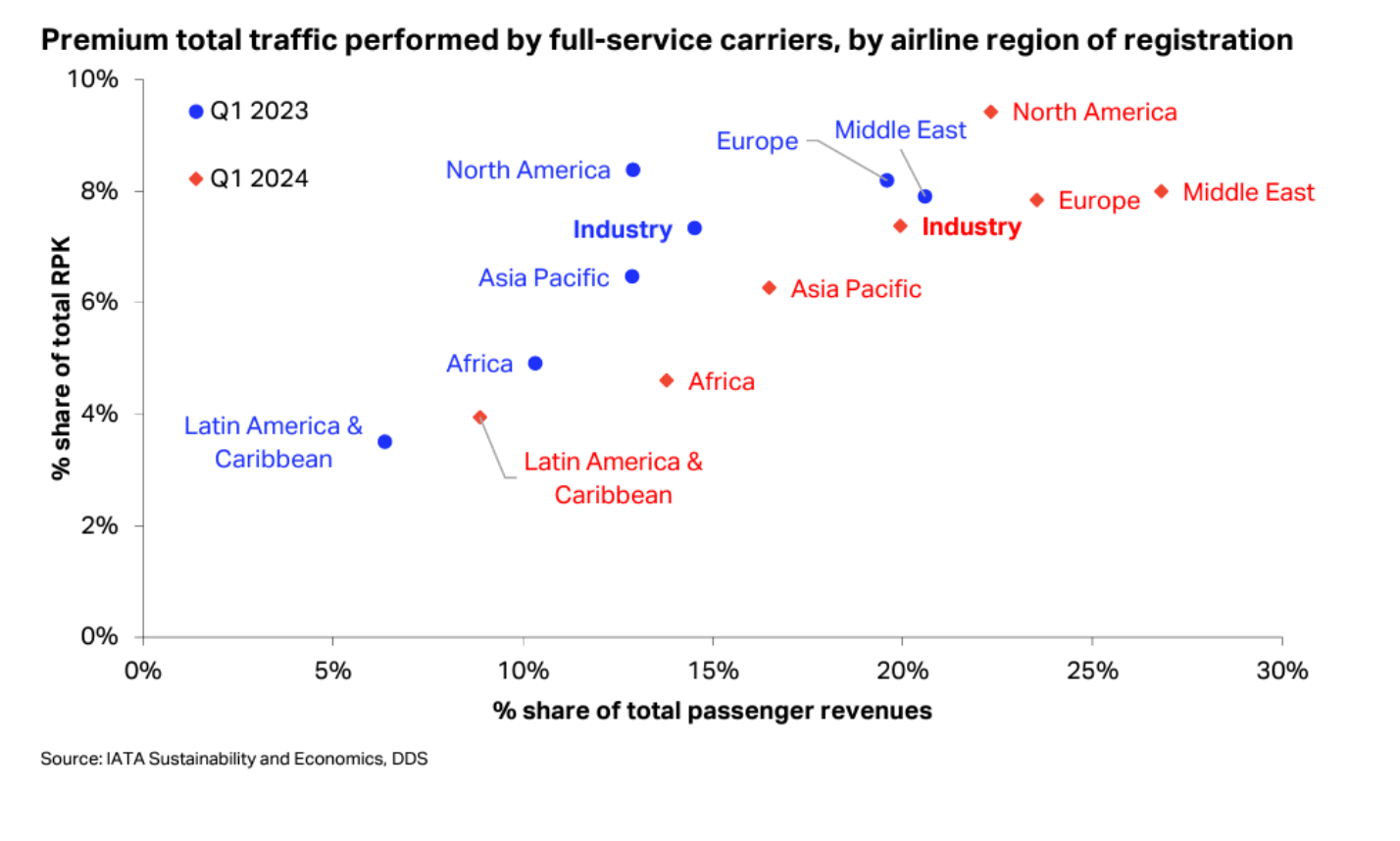

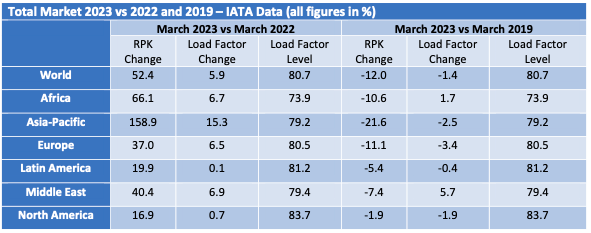

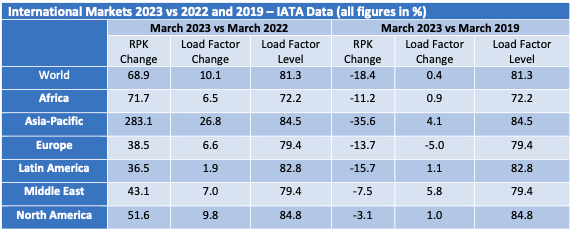

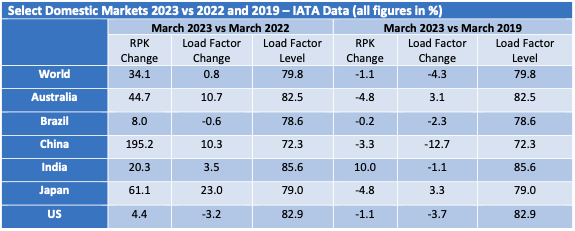

March 2024 RPKs were 0.1% higher than in March 2019, so recovery is official! Also, no region was more than 5% higher or lower than in 2019 so most of the extreme disparities in terms of recovery have worked their way out of the system.

International traffic recovery still lags domestic and shows greater variation by region, with Asia-Pacific conspicuously weaker than in 2019 and North America much stronger. It is striking that North American international RPKs are 11.0% higher than in 2019 vs only a 1.5% increase for domestic US RPKs: domestic traffic across the Americas was the quickest major market to recover after 2020 so it is tempting to assume that all is well, but markets such as the US are relatively mature limiting long-term growth potential.

The key markets driving domestic traffic volumes growth are China and India which as emerging markets with very large populations are vital to the aviation industry long-run fortunes.

Although some short-haul aircraft serve international routes nearly all long-haul aircraft do so, and this is reflected in the relative demand for single-aisle (narrowbody) and twin-aisle (widebody) aircraft. Aircraft demand can be measured in terms of aircraft in service and ASKs, the standard measure of aircraft capacity deployed by airlines which indicates how intensively aircraft are being flown. Single aisle aircraft demand on both metrics is higher so far in 2024 than in 2019 whereas twin-aisle aircraft are marginally weaker by aircraft in service and lagging more in terms of ASKs. The difference between the two metrics may be down to the gradual move away from very large aircraft such as the B747 and A380 towards the smaller B787 and nA350, resulting in fewer ASKs per aircraft unit.

It is hard to see the TA 2024 data series because it is only very marginally lower than TA 2019.

New Aircraft Supply

Supply chain issues continue to constrain Airbus’ ability to increase production and deliveries remain below their 2019 peak. It has revised down its delivery guidance for 2024 from 800 to 770. The latest status of Airbus’s production plans is:

The target date for increasing the A220 rate to 14 has slipped from 2025 to 2026. The only significant production targets not captured in the table above is the objective to raise A320 family production to 75 per month by 2027 (previously 2026) and to increase A350 production to 12 per month by 2028.

The latest status of Boeing’s production plans is:

The Alaska Airlines B737-9 incident in January has once again created significant uncertainty around Boeing’s ability to increase production of the Max. The FAA is investigating Boeing’s quality control systems and other related matters and has announced that it will not approve any increases in production until it is satisfied with Boeing’s level of compliance. Boeing has also announced that it will not seek certification of the B737-7 and -10 variants until it has engineering solutions for the engine inlet overheating issue resulting from extended engine anti-Ice operation in dry air. There is no definite timeframe to resolve this issue.

B737 inventory decreased from 110 at the end of Q1 to 90 at the end of Q2, including 65 B737-8 aircraft due to be delivered to Chinese airlines (these numbers above only include aircraft manufactured before the start of 2024). Inventory reduction accounted for 20 of 70 aircraft delivered in Q2 2024 compared to 65 of 67 in Q1 which suggests Boeing are making progress, although Boeing do not disclose how many aircraft manufactured in 2024 are in inventory.

As with the Max Boeing holds a significant inventory of undelivered B787 aircraft, c.40 at the end of Q1 vs c.50 at the end of 2023. Boeing has said it expects to deliver most of them in 2024. The inventory reduction of 10 aircraft compares with 13 total deliveries, suggesting that both B737 and B787 production is being severely disrupted. Boeing has not provided any delivery guidance for 2024.

COMAC of China achieved a significant increase in ARJ 21 deliveries and Embraer was in line with 2023.

Airline Industry Financial Performance

There has been some recovery in airline share prices since the summer which is most reasonably explained by lower fuel prices.

GOL of Brazil files for US bankruptcy protection in January. This was not a major surprise as GOL’s major competitors Avianca and LATAM had already done so during the pandemic and GOL had engaged in significant financial restructuring in the same timeframe.

The second largest airline by equipment value to fail is Lynx Air of Canada with a fleet including 9 X B373-8s. Lynx filed for bankruptcy protection in February, citing rising operating costs, high fuel prices, increasing airport charges, and a difficult economic and regulatory environment. Lynx was a low-cost airline that started operations in 2022 and some or all its problems are shared by most low-cost North American carriers up to and including Southwest Airlines, which have not benefitted from the strength of North American international traffic in the same way as the network airlines.

Sometimes airline financial distress comes in shades of grey rather than black and white. Although Pacific Airlines has ceased operations it has declared its intention to restart, and SpiceJet of India (43 aircraft) has suffered several adverse court judgments although it remains in business.

[1] RPKs is the acronym for revenue passenger kilometres, which is the product of the number of paying passengers and distance flown.

[2] ASKs is the acronym for available seat kilometres, which is the product of the number of available seats flown and distance flown.

Disclaimer